Hey. Remember that stationary store in your hometown? The one located at the top of the hill on the main drag? It had been around for three generations. You used to go there with your dad on Sunday mornings to pick up the newspapers. If he was in a generous mood he’d get you some gum or a candy bar. Maybe even a comic book. Try to remember the shape of the store. Where was the cash register? What weird things were on sale in the back? No matter, it’s all gone now. Been out of business for years, replaced by chain stores and the internet. Nobody wants mom and pop stationary stores anymore.

That melancholic tone, reminiscing through hazy, unreliable memories about objects and places that have vanished or are swiftly leaving the public consciousness is a central motif in the work of the Canadian cartoonist known as Seth (real name Gregory Gallant), and one that is central in his latest book, Clyde Fans by Seth.

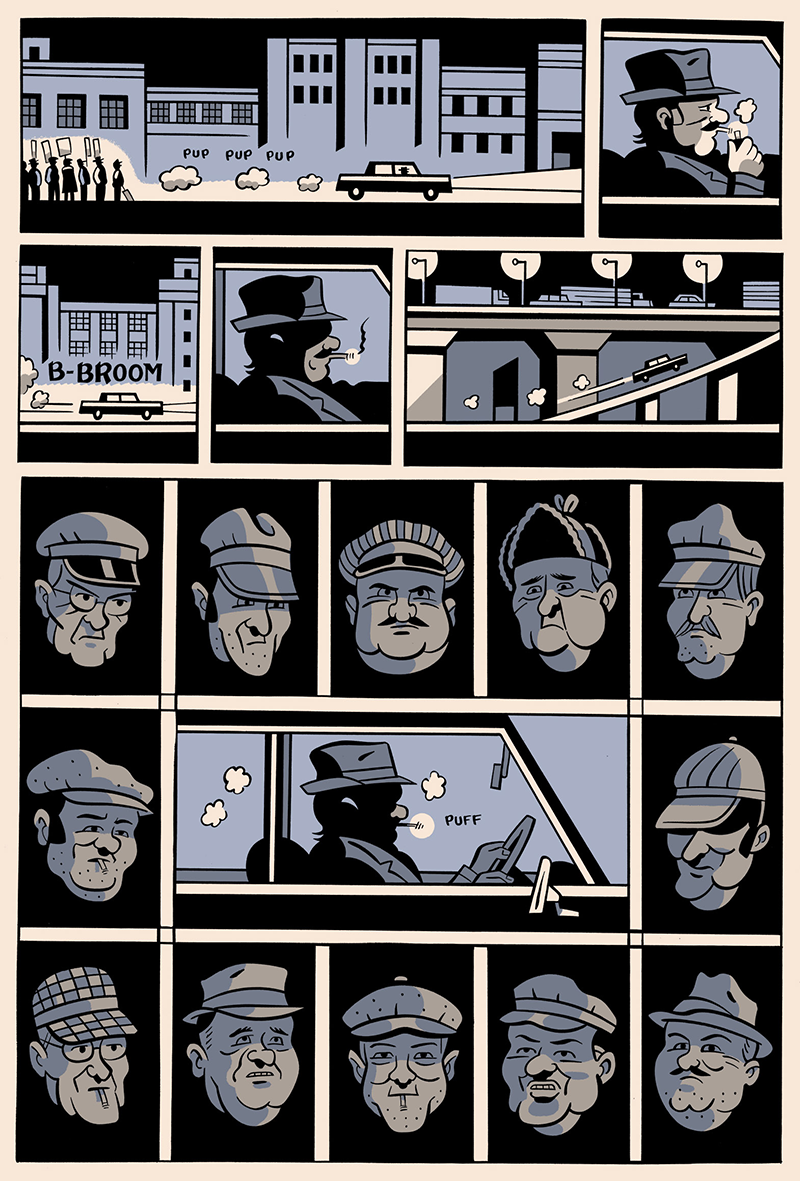

It’s very easy to recognize a Seth comic when you see one. He easily has one of the most distinctive art styles going these days, consciously evoking the style of early to mid-20th-century gag cartoonists like Peter Arno and Whitney Darrow Jr. Even his dapper personal attire — fedora, suit and tie, slicked-back hair, and round glasses — suggest someone who has stepped out of a bygone era.

Yet while Seth has a definitive fondness for the aesthetics of the 1930s and ’40s, he is no simple nostalgist, forever pining for the good old days that he never experienced (though there is a bit of that as well). Rather, Seth’s comics are frequently concerned with the notion of memento mori — a reflection on mortality and the notion that our earthly goods and pursuits are transient. He is more interested in the impulses that lead to nostalgia, especially those moments in history when a new way of life subsumes the old. And the characters who dredge up the past in his stories often recall sharp pain as much as they do joy.

Clyde Fans itself has been a long time in the making. Seth began it way back in 1998 in the pages of his (still-ongoing) one-man anthology Palookaville, where it has sporadically continued — a chapter here and there — through the ensuing years while working on other graphic novels and assignments (including designing best-selling series like The Complete Peanuts for Fantagraphics).

Clyde Fans tells the story of two brothers, Abe and Simon Matchcard, who inherit their absent father’s electric fan business. Abe is the businessman, the serious, dedicated one who, while good at his job and sociable, seems to tolerate little in life, his brother least of all. Simon, meanwhile, is the dreamer, a lost soul forever stuck in his head who cannot handle the outside world, especially those that involve dealing with other people.

The book jumps around in time, beginning at first with an elderly Abe in 1997 traversing the family home and storefront of his now-defunct business, directly addressing the reader about the ins and outs of his business and the art of selling. It’s a fantastic sequence, not just because of the way it blatantly breaks the traditional “show don’t tell” rule, but also for the way it maps out that building for us — a structure we will be returning to again and again throughout the book.

Then, we are taken back to 1957 as Simon decides against his brother’s better judgment to take a stab at being a traveling salesman. His trip is ostensibly a cringe-inducing failure until a worn down and rattled Simon experiences a mystical vision that leads him to a life of seclusion in the family home, taking care of his ailing mother, collecting postcards and talking to the odd assortment of knick-knacks that decorate his room. Abe, meanwhile, is also in a stasis of sorts, seemingly unaware of (or perhaps deliberately ignoring) changing technology and market forces — namely air conditioning — until it’s too late.

What we come to understand is that Abe, who eventually learns to embrace his brother’s solitude (or perhaps succumbs to it), is not as far removed from his recluse brother (or his runaway father) as he would like to admit. At the end, both brothers end up in the same place. Simon for not trying lest he lose his grip on his magical vision. Abe for trying too hard lest he fall victim to rumination.

Having been assembled over the course of two decades, one of the most interesting things about Clyde Fans is how much Seth’s drawing style has changed over the decades. Originally whisper-thin, his line has become thicker, bolder, more confident and more cartoonish (look at the elderly Simon’s forehead in the last third of the book if you don’t believe me). Thus, Clyde Fans itself becomes a physical manifestation of the impermanence of things.

Seth gets raked over the coals a lot for his “old-fashioned” aesthetic, stylized design and wistful melancholia as Seth himself has frequently acknowledged (he is not devoid of a certain amount of self-awareness). The collected edition of Clyde Fans certainly doubles down on these traits, packaged as it is in a hard-cased slipcover that bears either stylized lettering or cartoon imagery evocative of early to mid-20th century advertising on every side. The spine also contains an “index” listing everything from “appleyard” to “ukulele”, least you have problems locating those objects in the comic.

And yet there’s something fascinating in how a book about remembrance, longing, and the elastic nature of time comes in a package that so demonstrably calls attention to itself. In an era where we still worry about the physical book disappearing from the world seemingly dominated by e-readers and streaming media. Here is a work that refuses to be anything other than a tangible object, designed to call attention to its very physicality.

Clyde Fans is not Seth’s best book (that would be George Sprott, which deals with similar themes but in a much sharper and shorter manner) but there’s something in its haunting reverie and careful consideration of what is gained and lost in our passage to adulthood and the grave that calls to mind the slow obsolescence that surrounds our own little corner of the globe. How’s the stationery store in your neck of the woods holding up? •

All images provided by the author.

Images edited by Barbara Chernyavsky.