In high school, we swooned to boy bands and carried quarters so we could “arrive alive” after a teenage drinking binge. In middle school, we walked straight to airport gates to greet our grandparents as they tumbled off flights, rumpled in button-down shirts and pantyhose. And in elementary school, we read piles of books to earn personal pan pizzas from Pizza Hut and people told us we were special.

And we were special. As the high school graduating class of 1999, early on in our academic careers, administrators, teachers, and parents lauded us with the exclusive title of “last class of the century.”

Throughout our elementary, middle, and high school years, we got by on microwavable meals and believed our brains could look like fried eggs — any questions? — but we partied like it was 1999 anyway. On the brink of Y2K, my graduating class of 374 gathered on a warm evening in late May to fulfill our legacy. We were a large class crammed into a small gymnasium in West Central Wisconsin, our family members packed onto the bleachers after months of trading and haggling for coveted graduation tickets.

As one of 17 valedictorians in my class (yes, you read that right), I’d talked my way into what I considered to be the desired final speaking position. I wanted the proverbial final word—and it wasn’t about friendships or memories, thankfulness or nostalgia. What I had to offer was a simple piece of advice: “Wear sunscreen. If I could offer you only one tip for the future, sunscreen would be it. The long-term benefits of sunscreen have been proved by scientists, whereas the rest of my advice has no basis more reliable than my own meandering experience . . . I will dispense this advice now.”

That’s right. The class of 1999 was also the recipient of the spoken word piece, “Everybody’s Free (to Wear Sunscreen),” released by Baz Luhrmann in 1998 based off of music from the film Romeo + Juliet and an essay written by columnist Mary Schmich that was published in the Chicago Tribune in 1997. Though Schmich’s essay (and Luhrmann’s original rendition of the song) addressed the class of 1997, it was the single released in 1999 with its salutation addressed to “ladies and gentlemen of the class of ’99” that implanted in our minds after playing the song endlessly on our Discmans.

Standing before my graduating class swimming in a sea of baby blue mortar boards and gowns 20 years ago, I riffed on the song, parodying the lyrics to fit my classmates, our teachers, and our specific story. Since we graduated pre-smartphones, there may be a grainy home video of that speech somewhere, but as far as I know, my words are lost to the ages. And that’s okay because, re-reading the lyrics today, it’s clear the only advice any of us actually needed was spelled out in the original text.

. . . Trust me, in 20 years you’ll look back at photos of yourself and recall in a way you can’t grasp now how much possibility lay before you and how fabulous you really looked . . .

A snapshot of the class of ’99 is a time warp back to baggy jeans, chokers, and babydoll dresses. The photo is out-of-focus and slightly off-centered, imperfect and unfiltered, taken by a film camera without immediate gratification.

Quizzes in Seventeen magazine and MTV’s latest music videos informed our primping and fashion choices. Our identities took shape without guidance from YouTube superstars and #authentic Instagram influencers, cyber bullies or Photoshop. Today, our crooked smiles and unwelcome blemishes can be remedied with a Snapchat filter, but those newfound wrinkles, gray hairs, and baggy eyes are evidence of laughter, tears, long days, and even longer nights we’ve encountered over the past two decades.

. . . The real troubles in your life are apt to be things that never crossed your worried mind.

The kind that blindside you at 4pm on some idle Tuesday . . .

We came and went from our open high school campus, grabbing rides to the Burger King down the street or Slurpees from the 7-11. After school, we waited tables for less than minimum wage, then holed up in our rooms doing homework, isolated from each other. Our biggest concern was a sibling logging on to the dial-up internet for an epic AOL IM chat that clogged the landline.

But then the Columbine school shooting happened just mere weeks before our graduation day. And the twin towers collapsed on September 11 a few years later as we walked between college classes. AOL IM led to ICQ led to Facebook and shared Google Docs and Slack. Our attention and worries went from tongue-in-cheek “stranger danger” to being constantly on, hyper-aware. Today we use apps to meditate because life blindsides us at 4 pm on Tuesday, 5 pm on Fridays, and all day, all the time.

. . . Don’t waste your time on jealousy;

Sometimes you’re ahead,

Sometimes you’re behind.

The race is long, and in the end, it’s only with yourself . . .

The high school lunchroom was a figurative partitioned food tray with separated cliques — the jocks, theatre dorks, “pretty people,” and tech heads. We mixed in class when forced into group work and all got lost in the crowded halls during passing periods but our divisions — and labels — were clear.

If Facebook is any indication, many of these friend groups still exist, but as time blended us up and spit us out across geographical, financial, and professional landscapes, those clique divisions became hazier. Our life experiences and political leanings color our outlook about each other’s lives, but we all ultimately wrote our own stories. We no longer need each other’s approval to start smoking or quit pack-a-day habits, date or divorce, move home or move abroad.

. . . Don’t feel guilty if you don’t know what you want to do with your life.

The most interesting people I know didn’t know at 22 what they wanted to do with their lives, some of the most interesting 40-year-olds I know still don’t . . .. . . Be kind to your knees, you’ll miss them when they’re gone . . .

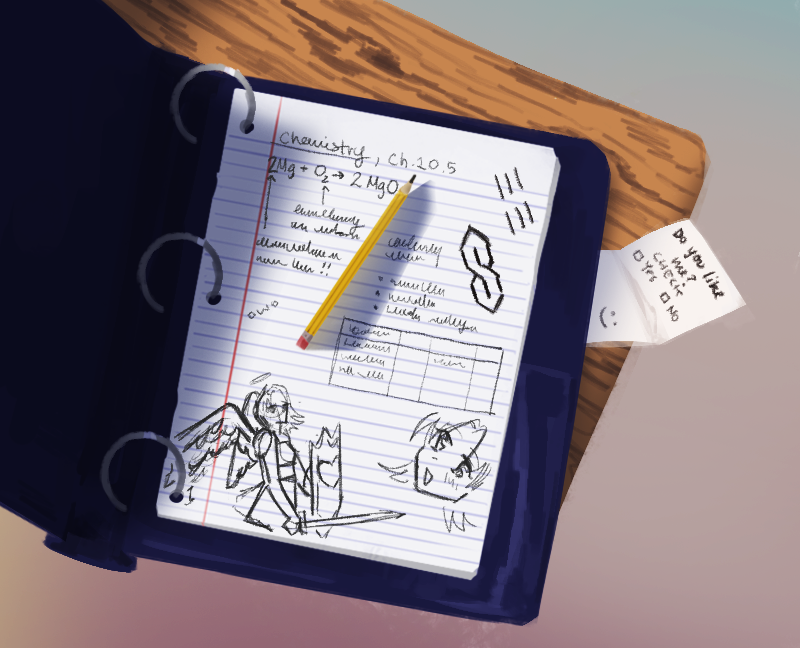

As our teachers droned on, scratching diagrams on the blackboard, we dashed off notes hidden conspicuously beneath our binders to be passed in the hall between classes. Folded within the creases were hints of crushes, tentative weekend plans, and — most often — the words “I’m so bored.” At eight and 12 and 18 years old, the days stretched like taffy, our lives a library’s worth of unwritten books filled with scraps of paper detailing characters, plot lines, and conflicts considered. We had all in the time in the world to figure out what to do tomorrow.

I knew when I walked out of the graduation ceremony 20 years ago, I was leaving town and never looking back. I had a career in mind. I started a business. I scheduled appointments in an online calendar. I texted colleagues while on conference calls. I threw myself all in. And then I started second-guessing my decisions. Closing in on 40, I mourn the days of folding nonsense notes into origami and am seriously considering a career change. I literally run away from the stress with a daily jog — a little bit slower and a little bit shorter than my runs were 15 years ago.

. . . Maybe you’ll marry, maybe you won’t, maybe you’ll have children, maybe you won’t, maybe you’ll divorce at 40, maybe you’ll dance the funky chicken on your 75th wedding anniversary.

Whatever you do, don’t congratulate yourself too much or berate yourself either.

Your choices are half chance, so are everybody else’s . . .

Long before Tinder, we watched romances blossom while laying out yearbook pages and riding long hours in coach buses to track meets, at Friday night football games and post-prom parties. Today’s ghosting was yesterday’s scouting out a new path to science class in order to avoid “that guy” we kind of liked last week. Instead of swiping left, we simply avoided eye contact while praying we wouldn’t be subject to such public humiliation.

But even those who fell lucky in love at 18 have traversed life’s ups and downs. We’ve all earned our fair share of emoji reactions over the years, often surprised by what we’ve achieved or how we’ve failed. We’ve lost limbs in war, walked out on domestic abuse, battled chronic pain … and we’ve competed at international athletic competitions, published books, and performed life-saving surgeries. Those “destined for success” at 18 are no indication of what success looks like at 38. Our choices were half chance, and no one — including and especially ourselves — could have written anticipated our future paths as we prepared to graduate.

. . . Dance . . . even if you have nowhere to do it but in your own living room.

Read the directions, even if you don’t follow them.

Do NOT read beauty magazines, they will only make you feel ugly . . .

Thank you, Spotify, Ikea, and feminist magazines for powering — and empowering — our lives.

. . . Work hard to bridge the gaps in geography and lifestyle because the older you get, the more you need the people you knew when you were young . . .

Flip through a photo album depicting the last class of the century’s early years: Arms draped over shoulders at Little League games, the third boy from the right with his eyes closed. An awkward image with our parents on the night of the homecoming dance, red-eye from the flash obscuring an attempt at a sophisticated smoky eye. A wide grin beneath the mortar board on graduation night, our younger siblings beside us, a look on despair in their eyes knowing they’re on their own now to fight the parental wrath.

Though social media is a double-edged sword for society as a whole, for my generation, it entered our lives at exactly the right time. We developed relationships — good and bad — in person, formed over uninterrupted conversations and through in-person interactions instead of avatars. We flew free from pre-conceived expectations from our home towns. Staying connected took work with occasional phone calls or a snail mail letter, and news sometimes felt achingly slow to arrive when it couldn’t be sent by text. Yet, as we started venturing from college to career, we reconnected through MySpace then Facebook groups specifically started to bring us back together.

Now racing toward 40, we’re losing an increasing number of our classmates every year, and we’ve said good-bye to parents, siblings, and our own children. What we wouldn’t give to add one more picture to that album, to celebrate one more milestone together, to freeze those moments relegated to photo paper. Fortunately, technology brought the last class of the century back together just when life’s transitions demanded extra support.

. . . Travel . . .

In the eighth grade, our class took a field trip to the Science Museum of Minnesota, about a two-hour bus ride from our small-town school in Wisconsin. Given a healthy dose of summer road trips growing up, a jaunt over the St. Croix River didn’t faze me at 13, but this was the first time some of my classmates ever left the state.

I understand and appreciate why many people never leave home (a 2015 New York Times article noted the average American lives within 18 miles of his or her mother) but moving away — far, far away — taught me resilience, patience, respect for others, and an appreciation for the time I spend in my “home town” because I make it back so rarely. Others my age who have lived or traveled widely in the years since graduation often echo my sentiment. Whether strolling through royal palaces in Europe, pushing physical boundaries hiking in the Andes, or volunteering in Sub-Saharan Africa, traveling over the past two decades has opened my generation’s eyes to the yawning gap between rich and poor, the physical realities of climate change, and the fact that we all have different languages, histories, and cultures, but none of those things makes anyone “less than.”

. . . Accept certain inalienable truths, prices will rise, politicians will philander, you too will get old, and when you do you’ll fantasize that when you were young prices were reasonable, politicians were noble and children respected their elders . . .

When did my graduating class begin lamenting about “kids these days?” We wallow in nostalgia over Dawson’s Creek reruns and an era of teen flicks featuring Leonardo DiCaprio or Alicia Silverstone. And we reshare clickbait about being a ‘90s kid if you wore slap bracelets, collected Beanie Babies, or slathered school supplies with Lisa Frank stickers. The truth is, today’s kids aren’t that much different than us.

Sure, they’ve traded grunge rock for trap hip-hop (a downgrade), the milk challenge for the Tide Pod challenge (both ridiculous), and Surge for Frappuccinos (admittedly, a major upgrade), but kids are kids at heart. We all stumble through familial strains, broken hearts, career crises, financial struggles, and personal challenges. We just all do it against different economic, social, and political backdrops.

. . . Be careful whose advice you buy, but, be patient with those who supply it. Advice is a form of nostalgia, dispensing it is a way of fishing the past from the disposal, wiping it off, painting over the ugly parts and recycling it for more than it’s worth . . .

Twenty years ago, as I looked out at my classmates — that special class of 1999 — I never thought I’d be reminiscing about the experience. I didn’t think much about the words I said then, and I didn’t think much about the lives we’d lead afterward.

Undoubtedly, as the class of 1999 gathers at reunions across the country this summer, they’ll recall favorite memories, take selfies with each other, swap tales of growing kids, and maybe make a helpful business connection or two. They’ll share life stories and offer advice to former teammates, lab partners, and bus buddies. They’ll remember classmates who have passed away and comment on each other’s appearances, accomplishments, and health. And as they take photos and reconnect with old friends, Prince’s “1999” blaring in the background and slightly higher-quality beverages in hand than two decades ago, hopefully, they’ll remember that one piece of advice that still remains truly timeless: Trust me on the sunscreen. •

Images illustrated by Barbara Chernyavsky.