The omission of airplanes in much artwork is understandable. It’s not a question of talent, but of choice and visibility. When used in art, the most visible kind of planes — those used for war and commercial purposes — signal the glorification of aviation’s base functions — to kill and to carry. There is no shortage of propaganda art featuring aircraft within the scope of warfare: smoking wrecks going down over a muddy European battlefield, or fighters strafing a South Pacific island. Airplanes’ other function — commercial — draws, blessedly, even less interest. There is something inherently tacky and inartistic about the jumbo jet, with its tuberous body, lumpy frontal node, bulbous engines. The same could be said of the jets’ central node, the international airport. As a crisscross of double-wide highways overseen by austere watchtowers and featureless grey buildings, these depots have all the charm of a postmodern jail. Through these portals, flying has become an accessible part of life, but as a passive event. We are flown, we do not fly.

There is one painting that captures well that difference. Painted by Frank Johnston, one of the Canadian Group of Seven artists, the work depicts a biplane performing aerial tricks high above a tapestry of rolling cropland. Titled Sopwith Camel Looping, it captures well the dizzying effect of flight, the splendor of movement, the possibility and freedom offered by a clear, open sky. You can smell the wet dog tang of fuel, feel the grip of the pilot’s hands on the stick, sense the buffeting against the wings and the aloofness of the distant earth — not far, yet not close.

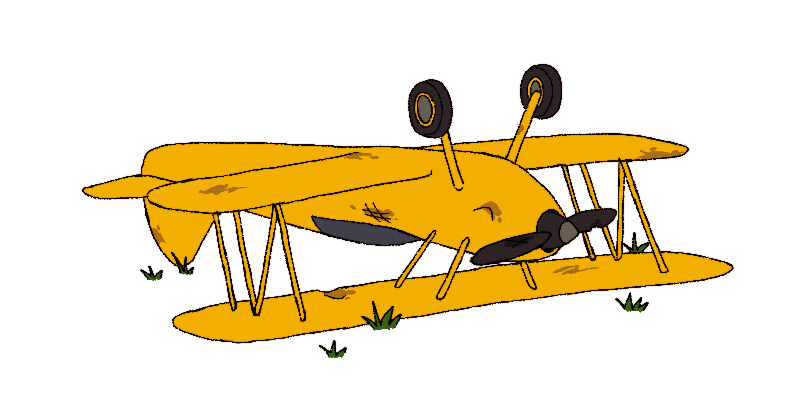

The pinnacle of aircraft beauty is unquestionably the open cockpit biplane, such as the one in Johnston’s painting. The perfect landing spot is a grass strip in a field. Like most ideas of perfection, this one coincides with an early memory. The first plane I can remember is a canary yellow biplane landing on the short turf runway (runway 08/26) at the Gladstone Municipal Airport. The airport, some nine miles from my family’s farm in southwest Manitoba, would most accurately be called an uncontrolled airport, or, even better, an airstrip.

At Gladstone Municipal Airport, there are no stores; engine oil can be topped up by cranking the handle fixed to a 55-gallon barrel. Likewise, a self-service pump with 100LL aviation fuel. There are no overpriced restaurants, but a bottomless supply of coffee and creamer can be taken with a ragtag collection of farmers. There is no control tower either, and therefore no custodian to sweep their eyes over the skies and maintain a semblance of order on the hidden aerial highways. That lack of oversight has its disadvantages, but most satisfying of all is the lack of airport security, and their brand of preventative scrutinizing that summons all the charm of a hospital run by a cadre of uniformed, teetotaling bullies. Instead, there are only the limits of flight to consider — weight and balance, lift and thrust.

Whereas a large airport allows access to the world (no matter how they try, airports can’t rid themselves of their penal atmosphere. The promise of arriving at some faraway destination becomes the reward for dealing with officiousness), the airstrip provides access to the sky. Pilots and passengers taking off from Gladstone Municipal don’t do so to travel anywhere, but to fly, and to take in the view. It is the very point of flight: to see and soar as a bird does, so that we might change our perspective.

According to homesteader records, the quarter of land on which the Gladstone Municipal Airport is found today was cleared of brush and homesteaded by Alexander Bruce in the summer of 1870. It was the first quarter in the area on which a homestead claim was filed. Virgin soil and bush. During the following century, the land was owned and farmed by a number of people, eventually becoming the property of the George Galloway family. Galloway was a pilot, and at his own expense, smoothed a landing strip, and opened it to other aircraft. These are not historical banalities. The fanaticism and gumption that made manned flight possible at the outset, were tapped from the same dream source used by those farmers. A direct path leads from Bruce to Galloway — a vision of the clearing, busting, and smoothing of the land.

When Galloway’s health began to fail in 1974, he sold the airport to the local municipality. Two new runways were built, and it was licensed with the Department of Transport and renamed the Gladstone Municipal Airport. At the time of its peak operation in the late 1980s, the airport supported an aerial spray business, a restaurant, and the Glad-Air Flight Training Center, which, between 1976 and 1987, graduated over 100 students. Learning to fly was cheap then, and a kind of piloting craze swept through the area. Farm kids got their wings, bought small, single-engine monoplanes, and began cruising the skies.

My uncle was one of those flyboys. He growled over his farm and others in a little underwing Piper, a single-seater. I only saw it fly once, when he landed it in my parents’ field, en route to its winter storage. Though I have no clear memory of that moment, perhaps a seed was sown that day, seeing someone I knew and loved emerge from the cockpit of this intangible freedom machine.

Years later, I studied physics, mechanics, and weather, and took the theoretical and practical exams needed to get a license of my own. I eschewed GPS, and that way came to know the land itself as a one-to-one map, as I threaded an invisible needle over the patchwork quilting of farmland. Tootling high over land I’d known my entire life, I saw it anew, with an improbable perspective. In those moments lay the finest discoveries. Thermals rising off plots of black, springtime earth rock the plane with violent turbulence. In summer, there are stamps of yellow canola, the green of immature wheat, and flaxseed so blue it seems to reflect the sky itself. When the midsummer heat reaches a head, clumps of storms, angled at the fore like a locomotive’s cowcatcher, sweep over the land, while fissures of lightning fire through the thunderheads. Hidden land scars — old railway lines, oxbow lakes, abandoned yard sites — emerge, revealing a hidden history. Herds of cattle look like handfuls of rice scattered on the land. In winter, the air is smooth over the cool, rippled top sheet of snow. At any time, it is the kind of landscape one can imagine a de Havilland Tiger Moth bouncing over, or Antoine de Saint-Exubéry laughing about; it certainly offers the best surroundings for 1930s-era barnstormers, such as those in the 1976 film, The Great Waldo Pepper.

Much like in that film, a plane passing over the farm is still an event. The unmistakable drone of an approaching aircraft is always enough to send my family onto the lawn, where, with hand to brow, we scan the skies for the source of the airborne furor. Each year, a pilot-cum-photographer knocks on the door to sell portraits he has taken while flying over our farmyard. These annual aerial shots grace the walls of homes across the prairies, cataloging the year-by-year changes from the only perspective that can take them all in.

Today, only the crop spraying business remains at Gladstone Municipal; the restaurant has closed, as has the training school. The airport remains unmanned except for a mechanic, whose workload is markedly light. A few crop dusters — Pezetel M18B Dromaders and Air Tractor AT-400s — take to the sky each spring. A row of pleasure crafts, mostly single-engine Cessnas and Pipers, gather dust. There are no longer so many who take to the sky for pleasure.

The other day, I drove past the airport. A yellow biplane, the one of my youthful memories, lay upside down, resting on its top wing. The metal plating of its underbelly was exposed, giving it the distressed look of an overturned insect. A few years before, while coming in for a landing, it had skidded in too fast, jumped the runway, and came to rest in a slough. It stayed there for years, its yellow tail jutting from the marsh reeds. The mechanic had finally dredged it and was scavenging it for useable parts.

The day was hot — approaching 40°C — and there were no takeoffs planned. In that hot air, windless and thin, it would take the entire runway, maybe more, to create the lift needed to take off. Instead, the only action was a farmer baling a thin cut of hay along the near side of the runway. On the other, a sallow crop of canola withered in the heat. Suddenly, as though before my eyes, the buildings seemed to slump and age. The grounded planes looked tired and gimpy. The entire airport seemed to shrivel, threatening to crumble with a touch.

“Ask ‘Why fly?’ and I should tell you nothing,” wrote Richard Bach in A Gift of Wings, his devotional to flight (its French title, Liberté sans limites, captures better its aspirational writing). “I suspect the thing that makes us fly, whatever it is, is the same thing that draws the sailor out to sea. Some people will never understand why and we can’t explain it to them. If they’re willing and have an open heart we can show them, but tell them we can’t.”

From Gladstone Municipal, I’ve taken family and friends with me into the skies. We rise into the sweet spot, 1000 feet or so above ground level, where the visual connection to the earth is still palpable, but the distance is immutable. For some, it’s a muddling height (more than a few were unable to recognize their own houses and farms from above), for others illuminating.

The journeys are typically quiet, the thrum of the engine unbroken except for an occasional interjection to look at this or that. There is little to say when everything, one’s entire world, is spread out, laid bare, minimized, and expanded all at once. It is an abeyance of one’s life, a chance to look and think without needing a question to answer.

As Beryl Markham has written, in her wonderful book about flying, West with the Night, “There are all kinds of silences and each of them means a different thing. There is silence after a rainstorm, and before a rainstorm, and these are not the same. There is the silence of emptiness, the silence of fear, the silence of doubt… Whatever the mood or the circumstance, the essence of its quality may linger in the silence that follows. It is a soundless echo.”

Each time I take off, I battle the silent fears of crash reports, of self-doubt, and the distrust in the immutable laws of physics, a distrust that is inherent in mankind. Flying becomes a confidence trick played upon the self. Up there, drifting upon nothing and through nothing, there is only one’s own reserves to pull from. There is nothing but the context and one’s reaction within it. If something should go wrong, there is no help, no out, no withdrawal.

I never flew with my uncle. He is dead now, and another of life’s opportunities has gone forever. The time was never right, or our paths did not cross in that way. But knowing he and I flew the same sky, shared the same air, over the same land, to and from the same airport. Bach alludes to this. “It is perspective that shows the barriers between men to be imaginary things, made real only by our own believing that barriers exist, by our own bowing and cringing and constant fear of their power to limit us…We may even find, at the end of our journey, that the perspective we’ve found in flight means something more to us than all the dust-mote miles we’ve ever gone.” Gladstone Municipal has not crumbled. It is indestructible because it offers only what all airports must: a flat stretch of land and limitless destinations.•