Can a work of art be deeply flawed and still be great? One of the reasons that some once-revered works in the Western canon have been treated so shabbily in recent years is that, once a new lens is introduced that illuminates their flaws, critics have been exceptionally severe. But great things need a certain kind of patience and understanding to exhibit their greatness, especially as time passes and new critical standards come into play.

With this in mind, I want to write about Proust, a figure much elevated in the modernist canon and, surprisingly, not condemned the way other works have been. This may be because of Proust’s persona as it has popularly come down to us (gay, Jewish, engaged in social satire). But I also think it is because few educated people have read his masterwork, In Search of Lost Time, in its entirety. (I use the literal translation of the French, A La Recherche du Temps Perdu, though I prefer the more lyrical, looser translation by C.K. Scott Moncrieff and Terence Kilmartin, Remembrance of Things Past (the title taken from Shakespeare’s “Sonnet 30“).

Yes, everyone knows those superior individuals who boast about having read A La Recherche (as they are likely to refer to it) every five years. But these people are either exceptionally tenacious or exceptionally mendacious. The question is: If one actually reads Proust’s novel from beginning to end, what conclusion does one reach? I present myself as a test case.

Having spent a good chunk of the COVID years reading — and finishing — Proust’s seven-volume novel, I can report back from the other side. Books I and II are exceptionally original and engrossing. There is the well-known opening discussion of the narrator’s anticipation of his mother’s bedtime kiss, an event that Marcel, the fictional protagonist with much in common with the author, obsessed about as a child. The first book, “Combray,” also contains the famous Madeleine scene in which Marcel dunks his cookie in a cup a tea and has memories of his childhood flood back to him. At one point Proust presents what might well be called the thesis of his magnum opus: “we are disillusioned [by things] when we find that they are in reality devoid of the charm which they owed, in our minds, to the association of certain ideas.” This could be reduced to Oscar Wilde’s pithier version: “There are only two tragedies in life: one is not getting what one wants, and the other is getting it.”

But in Book III, The Guermantes Way, problems begin to crop up. Marcel is now an adult and hence a participant in the society that, previously, he had surveyed from the more generous viewpoint of a child. In the opening section, one could think around the child’s perspective and imagine Proust as engaging in social satire. But once Marcel grows up and becomes a central participant in the action, the satirical aspect gets a bit sour. Marcel has become a snob, dazzled by the aristocratic characters he engages with. Although some degree of satire is maintained toward this group, it loses its edge as Marcel is inclined to adopt their condescension for people of lesser pedigree. There is, notably, his superior attitude toward the bourgeois “petit clan” that he nonetheless frequents, partaking unapologetically of the copious food and drink provided by its hostess, Mme Verdurin (an esthete whose acolytes hail from the professions and the arts). He has even greater condescension, bordering on contempt, for more marginal groups.

Jews, for example. Marcel reports with painstaking zeal on the Jewish presence in the society he depicts and how these individuals are received in both the aristocratic and the bourgeois communities. Marcel occasionally offers a qualification: Jews, he notes, had “plenty of wit and good-heartedness,” despite the fact that “their hair was too long, their noses and eyes were too big, their gestures abrupt and theatrical, it was puerile to judge them by this.” But of course, he and everyone else does.

An abiding touchstone in Proust criticism is that Proust himself was Jewish and therefore to be acquitted of anti-Semitism. In fact, he was half-Jewish; his mother and grandmother were Jews, but not his father. Interestingly, Marcel’s mother and grandmother are the only uninflectedly positive characters in the novel; in portraying them as not Jewish, the author can be said to remove this presumed taint in his fictional representation of them.

The same wish-fulfillment seems to operate with respect to homosexuality in the novel. Proust was known to be homosexual and yet his book is emphatic about Marcel’s heterosexuality, with homosexual slurs being even more pronounced than Jewish ones. Indeed, the two are sometimes linked: “I have thought it as well to utter here a provisional warning against the lamentable error of proposing (just as people have encouraged a Zionist movement) to create a Sodomist movement and to rebuild Sodom.”

Homophobic references appear early in the novel and become increasingly frequent and emphatic as it continues. The fourth book, Cities of the Plain, contains an exhaustive discussion of the life of “inverts,” with certain unsavory ideas returned to repeatedly in later books as the narrator is drawn to explore, in quasi-anthropological fashion, a secret society that seems to exist everywhere he looks. It is a voyeuristic fixation at once off-putting and tedious.

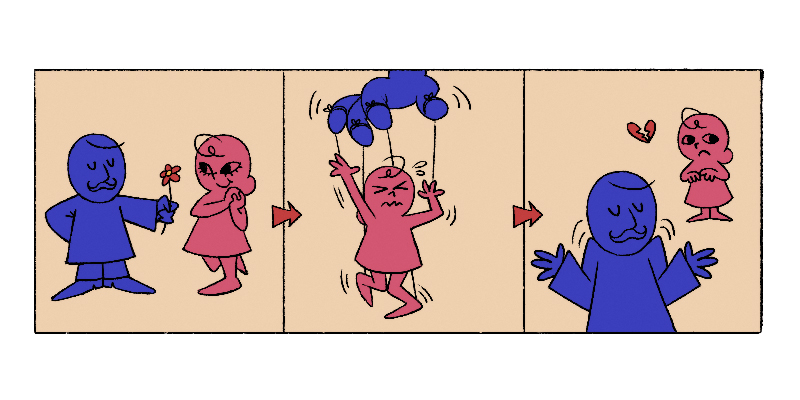

But what came to irritate me most, as I continued into the later volumes, was the depiction of what Marcel defines as love: “It is a mistake to speak of a bad choice in love,” he notes at one point, “since as soon as there is a choice it can only be a bad one.” In the episode in the first volume, “Swann in Love,” which had appealed to me when I read it in college, the behavior seemed fresh and in keeping with my adolescent view of love as romantic projection and suffering. But the pattern gets enacted over and over again in the course of the novel as Marcel becomes infatuated with a series of women. In each case, he enters the relationship casually, develops an obsessive fixation that seeks to control the woman’s every move, then finally, after what seems like an endless litany of repeated suspicions and parsings of trivial details, falls into indifference as the obsession loses its hold.

These romantic convulsions can be said to hearken back to the anxiety the child Marcel felt about his mother’s bedtime kiss — the back and forth between anticipation and disappointment, desire and regret. That seems to be the conditioning experience behind the pathology of his romantic relationships. But such an understanding does not prevent this repeated trajectory from being very, very tiresome.

And yet as I neared the end of the novel, I found my interest revived. In the last scene, which encompasses a considerable portion of the last book, Marcel attends a party after a lengthy period away from society. He has spent time in a sanitarium for his weak lungs, and World War I has intervened. The party is a narrative curtain call for almost everyone we have come to know over the course of the seven volumes.

When Marcel enters the drawing room he at first fails to recognize the people there because they are so much older, their former appearance revised: “they had endeavored, with the face that remained to them, to construct a new beauty for themselves. Displacing, if not the centre of gravity, at least the central point of the perspective of their face, and grouping their features around it in a new pattern.” Just as these people’s features have been re-arranged, so have the relationships among them. Those who supported Dreyfus in the famous case of the Jewish officer falsely accused of treason are now mixing freely with the anti-Dreyfusards. A character, once scorned as a vulgar Jew, has become a successful playwright and accepted fixture in society. The bourgeois hostess has now remarried and become part of the aristocratic set from which she had been barred, and the former courtesan has become popular in this group as well. It is a kaleidoscope of revisionary images and relationships.

The narrator has also changed. He has become inured to what he had once either desired or disdained. It is as though he now responds to life with the indifference that he had responded to the women he was once fixated on. This is the detached perspective that can retrieve the past and create art: “a long process of assimilation has converted [what came before] into a substance that is varied of course but, taken as a whole, homogeneous.” Marcel has transferred all his snobbish energy from social minutiae to human mortality: the crumbling of former beauty and status, and a softening of once-entrenched opinion.

Having completed my reading of this enormous novel, my conclusion is as follows: If one reads a little of Proust, one thinks he is a genius; if one reads more, that feeling is likely to curdle; but if one reads the whole thing, one’s admiration is revived. Since more people read very little, that probably accounts for the novel’s reputation, but only those intrepid few who make it to the end, of which I can now count myself one, are in a position to fully appreciate the achievement. (I should add that the penultimate, sixth volume of the novel contains sexual elements relating to Albertine’s possible lesbianism and Charlus’ S&M tastes that astoundingly escaped censorship. I assume this is because so few managed to get that far. Joyce’s Ulysses, condemned for less, is comparatively easy reading. It is noteworthy that C.K. Scott Moncrieff’s English translation of Proust (1921-1930) appeared around the time that Ulysses was judged to be obscene (1922)

Proust’s work is very much a mixed piece of art — full of boring, irritating, unpleasant preoccupations and fixations. But apply a larger lens — as Marcel does at the end inside the novel — and one sees the thing whole, as a great work, one that mirrors our weaknesses and limitations and, as such, is a testament to a tragic view of life — to the inescapable fact of mortality and its leveling effect on us all. To represent this profoundly human story is certainly a mark of greatness.•