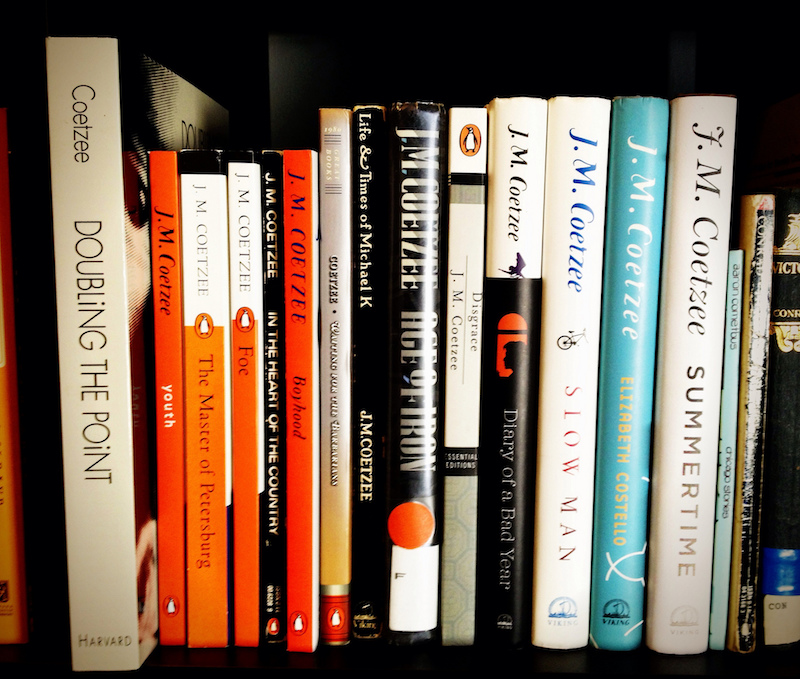

Like the namesake of his most recent novels, J. M. Coetzee speaks to us in parables. The Childhood of Jesus and The Schooldays of Jesus, like Disgrace and Summertime before them, give us politically charged stories seemingly without side. This encourages the Nobel laureate’s reviewers to become Coetzeeologists, attempting to parse out whether the book before them sets opposing tensions in play for art’s sake alone, or whether we can discern a clear moral leaning beneath the tensions. We assume Coetzee came to the story with an open mind but did he leave with one too? What’s he trying to say?

Since about The Master of Petersburg, most of Coetzee’s novels have used oppositional ideas to power their dynamos. The reader’s changing sympathies fall into a sort of dance with the story itself: Each revelation shifts our allegiances, tilting the axis of the book. It’s like watching a courtroom drama where the very ideas by which we live our lives are put on trial, and we’re not yet certain whodunit. In Disgrace, a college professor in Coetzee’s native South Africa takes sexual advantage of a student and then is himself savagely victimized — in what measure has justice been served? In the underrated Elizabeth Costello, the eponymous fictional novelist accuses a fictionalized version of the real novelist Paul West of depicting the horrors of the Holocaust in a way that effectively exploits them; as we watch her argument unfold, we find ourselves first cheering her on, then recoiling. This is fiction at its best.

In the most accomplished of these books, Coetzee paints his worlds, and his arguments, in vivid colors. Summertime tells the story of the fictional biographer of the fictionalized J. M. Coetzee interviewing the fictional people (or are they merely fictionalized? we’re never sure) that “Coetzee” interacted with during the mid-1970s. The character of “Coetzee” himself is drawn as a sort of semi-noble fool, a bungler whose idealism may be usefully righteous (or may not) and whose lack of success may come down to either his own personal failings or those of the society in which he lives. Or both. Or neither. As a woman with whom he was briefly infatuated — the Brazilian dancer Adriana — begins her chapter by describing what she tells the biographer were Coetzee’s inappropriate attentions toward her daughter when he tutored the girl in Cape Town. But as her story evolves, it soon becomes clear to the reader that she herself was the object of Coetzee’s wholly age-appropriate affections and that he likely looked upon the Señora’s daughter as nothing but a promising student he was eager to encourage. As Adriana lays out her version of the facts in a long monologue interrupted only by brief questions from her interlocutor, her voice engraves itself upon the reader — the way she speaks is entirely unlike Coetzee’s own and unlike that of the other chapters’ subjects: Coetzee’s dutiful colleagues, his simple-minded cousin, or the preoccupied woman with whom he shares a brief affair.

Adriana, a dance instructor, describes how the Coetzee she knew did not have any natural feeling for dance, moved like a marionette:

But that is not how you dance! That is not how you dance! Dance is incarnation. In dance it is not the puppet-master in the head that leads and the body that follows, it is the body itself that leads, the body with its soul, its body-soul. Because the body knows! It knows!

Reviewers sometimes get on Coetzee’s case about dry or dispassionate prose, but as the above makes clear, this is rarely just. What delights the reader most pointedly in Summertime is how compelling and convincing the various voices are, and how distinct. Because those voices each bring bright and unswerving opinions to bear on the facts we think we know — and because those voices ring so true — the reader’s allegiances not only shift repeatedly, they shift powerfully. In Adriana’s telling, Coetzee, who tutored her daughter, was not only awkward (“a man dancing naked, who did not know how to dance”) but monstrous (“why do you think I did everything I could to keep my daughter away from him while she was still young, with no experience to guide her? Because from such a man no good can come”). It slowly dawns on the reader that Adriana herself may be the monster, re-creating Coetzee’s attentions as a kind of bogeyman for her own anxieties about her paralyzed and dying husband. Then again . . .

In Youth, the second of Coetzee’s fictionalized memoirs of his own early life, the protagonist, an aspiring poet, rudderless in London, flirts with abandoning poetry for prose. This may be a sort of relief for the buttoned-down boy, because “prose, fortunately, does not demand emotion: there is that to be said for it. Prose is like a flat, tranquil sheet of water which one can talk about at one’s leisure, making patterns on the surface.”

This is not a fit description of the prose we find in Summertime or Disgrace. Nor does it describe Waiting for the Barbarians or In the Heart of the Country or Life & Times of Michael K.

The Childhood of Jesus and The Schooldays of Jesus are another thing. Both novels feature combatants with opposing views, lots of conflict, and reasonably high stakes. But the people we meet there never quite feel like people and the country they wander never feels like a place — it feels like a philosophical proposition, the characters half-sketched, prose emptied-out not only of realism but of the same thing Señora Adriana’s aims to cultivate in her dancers — she doesn’t use the word duende, but it’s just what she tries to cultivate: the motion of the human soul in dance.

As Childhood opens, a pair of refugees, Simón and his young charge David, have landed on the shores of a new country, washed of nearly all their memories by the Lethe they’ve crossed to get there. David’s mother is missing but Simón is sure they’ll know her when they see her. When David finds himself drawn to a young lady playing tennis at a gated community called La Residencia, Simón begs the woman, Inés, to serve as David’s mother, and she eventually compiles. Why? We’re never sure. Because she remains a mystery to Simón, she remains a mystery to the reader too; Coetzee can only ever drift his unreliable narrators into indeterminacy, never fact. Simón works as a stevedore until an accident nearly cripples him, and David runs away from boarding school.

Schooldays commences weeks later as Inés, Simón, and David arrive in the city of Estrella, having decamped thence to escape the truancy squad, and are there encouraged by a pair of spinsters to enroll David in the local Academia de la Danza, “an academy devoted to the training of the soul through music and dance.” There they meet Ana Magdalena — one of the few members of the school’s staff not named for a Dostoyevsky character. “In dance,” she declares, “we call the numbers down from where they live among the aloof stars.” Simón, a cold fish and quietly preposterous even when compared with Coetzee’s other cold protagonists, cannot get his head around mysticism and doesn’t know if he should.

This is the central tension of Schooldays: the play between reason and enthusiasm, between passion and dispassion. The post-Enlightenment world is hereby put on trial. On the one end of the passion/dispassion spectrum, we find Ana Magdalena (of whom one character remarks “for intellect she substituted enthusiasm”). On the other, we find Simon, who “thinks of himself as a sane, rational person who offers the boy a sane, rational elucidation of why things are the way they are.” Much of the philosophical freight the book unloads turns out to be a question Simón ask himself: “Are the needs of a child’s soul better served by his dry little homilies than by the fantastic fare offered at the Academy?”

David is a curious variation on this pattern; half the time, he’s just like anyone else. The other half he is the host of a potent transcendence. Everyone agrees of David that “he’s an exceptional child” and “has a great future ahead of him.” But no one can seem to characterize in just what way David is exceptional if indeed he is. All children might seem eccentric when compared with their square forbears, and David is no different. Because no other children are described in any detail here, David has no foil. Who is he different from?

Moreover, except for Ana Magdalena and a man revealed halfway through the novel as a murderer, all of the citizens of the country without memories strike the reader in the same way they strike Simón, as basically bloodless. In Childhood, he begs a well-meaning companion:

Everyone I meet is so decent, so kindly, so well-intentioned. No one swears or gets angry. No one gets drunk. No one even raises his voice. You live on a diet of bread and water and bean paste and you claim to be filled. How can that be, humanly speaking? Are you lying, even to yourselves?

But it is Simón, more than anyone, who winds up embodying this torpidity, and the novel — told entirely from his free-indirect point of view — suffers irreparably. To write in a gray style about a gray place is to fall prey to the imitative fallacy. And worse, the major themes at play: reason versus enthusiasm, yes, but, more specifically, the irrational dangers of eros, the necessity of “the soul” in dancing, and the struggle of parents to at once guide their children and become more like them are all subjects Coetzee has explored more successfully elsewhere. Indeed, there is no idea in Schooldays that is not handled more vividly — and at a fraction of the length — in the Adriana section of Summertime — 40 pages, tops.

There are nevertheless lots of minor ideas in Schooldays that might, in theory, produce compensatory pleasures. Indeed, as with Childhood, the baggy structure of the novel gives Coetzee space to pit Simón against whatever forensic opponent might best banter back. Often this is David: The two debate the meaning of death, why feces disgusts, and whether it’s a good idea to eat sausages. Here in Schooldays, Simón spars mostly with the earthy and histrionic handyman Dmitri, but with a few others as well. Any number of philosophical cans are kicked around (in less depth and less convincingly than they were in Elizabeth Costello), and any number of oddities introduce themselves only to be left unexplored. As in Summertime, bad dancers are compared here with marionettes; much later, the spinsters who fund his education give David an old marionette as a toy. Why the symbol again? We can’t say. It’s potent, sure, but with what? The reader begins to suspect Coetzee himself doesn’t know, and that he reached for the puppet precisely because he doesn’t know. It isn’t mentioned again. Simón, on another occasion, pointedly asks David what the boy means when he tells his guardian he’s slept in the same bed as the adult attendant Alyosha at his school. This is normal, the boy says, because “anyone who has bad dreams can sleep with Alyosha.” That’s all we hear about it.

Finally, we come to the vexation of the titles. Who is this Jesus and why does he not appear? We are not even sure whether it is David or Simón himself (a man who eschews riches, blasts hypocrisy, studies chastity, and turns the other cheek) the title is intended to allude to, if either.

The only real clues we get are David’s name and nature. Simón, you see, does not “recognize” the boy, does not sense his truth or know his original name. Or so the boy and everyone around the boy believes. But how Simón would know these things or what use they would be were he to discover them is not explored.

In Boyhood, the first of Coetzee’s autobiographical novels, the young, fictionalized Coetzee becomes uncomfortable with his teacher’s conception of the divine:

His resistance to Mr. Whelan’s Scripture lessons runs deep. He is sure that Mr. Whelan has no idea of what Jesus’ parables really mean. Though he himself is an atheist and has always been one, he feels he understands Jesus better than Mr. Whelan does. He does not particularly like Jesus — Jesus flies into rages too easily — but he is prepared to put up with him. At least Jesus did not pretend to be God, and died before he could become a father. That is Jesus’ strength; that is how he keeps his power.

There will likely be a third installment of the Jesus trilogy and, if I had to guess, I’d guess it will focus on unknowability (a usual preoccupation of Coetzee’s and one that’s made use of only glancingly in Schooldays). David may well die before he becomes a father and the whole operation grind to a humdrum halt. But I could be wrong. Boyhood and Youth were unexceptional novels as well, at least for a writer with Coetzee’s powers, and it wasn’t until the conclusion of that trilogy that their author unexpectedly threw all that had come before it into metafictional chaos and changed utterly our conception of the whole. He might do it again. If so, count me in. Coetzee at his best is the best we’ve got. •

Images courtesy of Leukos., UC Irvine, christopherdale, lakewentworth, ShyViolet09, susy ♥, and andessurvivor via Flickr (Creative Commons).