Ventriloquism

“I only became famous in October,” mumbled Shehan Karunatilaka as he leaned on the wall of the Chandni Chowk metro station and lit a cigarette.

Here, in downtown Kolkata, with its crumbling office blocks and chaotic sidewalks, the long-haired, eyebrow-pierced writer from Sri Lanka was about as conspicuous as a dirty napkin in a dingy bar.

“And I’ll stop being famous next October.” oc

In October 2022, Karunatilaka won the Booker Prize for The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida, a whodunnit set in the afterlife. Maali Almeida — “photographer, gambler, slut” — recently dismembered and resurrected in a purgatorial visa office, has a week — seven moons — in which to figure out the identity of his murderer and ascend into the Light. The list of suspects is long: his apparent girlfriend, his actual boyfriend, irate warlords, genocidal politicians, and any number of disdained lovers fellated in bars, back alleys and war zones. On top of all that, there are demons to avoid, shamans to supplicate, a closet to guard, and a stash of photographs under the bed that might bring tumbling down the whole house of cards that is Sri Lanka in the late ’80s.

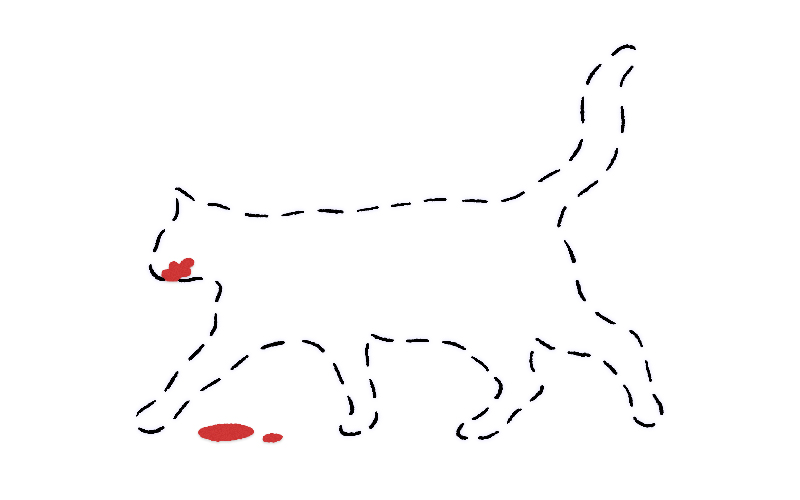

At 48, Karunatilaka has become — after, arguably, Michael Ondaatje — Sri Lanka’s most internationally-renowned novelist (like any major cultural award, the Booker brings with it dopamine, cash, and a modicum of fame). His prose is observant and heteroglossic, castigating gently the foibles of ordinary people and mocking ruthlessly the sins of the powerful. His ventriloquizing can be dizzying: his narrators are drunk boomers and ghosts of the Colombo hipster elite; profiteers from the island’s colonial past; self-driving cars trying to work out the trolley problem; cats trapped in prison riots; or, as in the short story “The Birth Lottery,” the inner monologues of 42 different Sri Lankans — human, canine, ichthyic, viperine — from the beginning of the world to its end.

When it comes to doing voices, Karunatilaka has had a lot of practice. The Colombo he grew up in was closer to a provincial backwater than the bustling metropolis it is today. As children, he and his younger brother Lalith were often dragged to grownups’ parties. Afterwards, Shehan would entertain Lalith by imitating the aunties and uncles they’d witnessed getting drunk over dinner.

As a young man, and like many writers before him — Dorothy L. Sayers, Salman Rushdie, F. Scott Fitzgerald — Karunatilaka plowed his furrow in advertising. This allowed him to a) meet his future wife, the art director and designer Eranga Tennekoon; and b) do more voices.

In a radio ad he created for SriLankan Airlines around the time he was completing his first book, an old uncle pretends to be a hip young dude to get a discount on a flight.

“Sir, you have to be below 27,” implores the airline employee at the other end of the phone.

“Dude, I am 22, chill!” Uncle replies. “Why you are, err, tripping?”

Right there you are transported, between the blustery and the bizarre, into the pages of Karunatilaka’s debut novel, Chinaman: The Legend of Pradeep Mathew, and the singularly cantankerous voice of its narrator, WG Karunasena.

The Chinese

“Fancy being done by a bloody Chinaman,” said 1930s English batsman Walter Robins in a jibe that today would have required a disciplinary hearing. It was Mathew’s bread-and-butter delivery. Pitching outside the batsman’s bat and cutting into him. Ellis Achong, a West Indian of Chinese descent, dismissed Robins with one such delivery, and sparked both the outburst and the term.

Shehan Karunatilaka, Chinaman: The Legend of Pradeep Mathew

At once a rambunctious shaggy dog tale about a missing cricketer and — via rambling digressions, alcoholic asides, and subtextual meanderings — an irascible history of modern Sri Lanka, Chinaman became something of a cult novel in a subcontinent obsessed with cricket and its lore. If someone brought it up at a party, you knew you would get along. Ondaatje himself called it “a crazy ambidextrous delight.”

Armed with a cirrhotic liver and industrial quantities of arrack, two-time Ceylon Sportswriter of the Year WG Karunasena attempts to chronicle the life of the chinaman bowler Pradeep Mathew, the greatest Sri Lankan cricketer who never was. With his neighbor Ari Byrd, trusty Watson to his alcoholic Holmes, WG must navigate conspiracy theorists, creepy bureaucrats, gun-toting Tamil Tigers, overexcitable trishaw drivers, and at least one “wiretapping midget,” to get to the heart of the mystery of Pradeep Mathew’s disappearance and his erasure from all the cricketing archives.

“Though I normally dislike the label ‘postcolonial’ and am reluctant to use it, I feel that Chinaman is really a postcolonial novel in the way it engages with history, its construction, its obliteration, and its writing or rewriting,” Supriya Chaudhuri, Emeritus Professor of English at Kolkata’s Jadavpur University, tells me. Chaudhuri used to teach a course on The Literature and Culture of Sport that included Chinaman and Joseph O’Neill’s Netherland (2008) under a rubric appropriated from C.L.R. James’s Beyond a Boundary: “What do they know of cricket who only cricket know?”

“Both were postcolonial novels contrasted to an earlier, colonial history of writing about cricket,” she says. “Both were set against histories of violence and conflict, using the beauty, inexplicability and absurdity of the game of cricket in order to understand why human beings live the lives they do.” Netherland, James Wood argued in the New Yorker, “is a postcolonial re-writing of The Great Gatsby.” Chaudhuri believes Chinaman is similarly in conversation with what she calls “the greatest of all postcolonial novels,” V. S. Naipaul’s A House for Mr. Biswas (1961).

“The dying Gamini Karunasena’s alcoholic, obsessive pursuit of ‘the legend of Pradeep Mathew,’ a brilliant spin-bowler of the 1980s whose career and achievements (many of them in a losing cause, with the Sri Lankan team comprehensively beaten by stronger opponents) are progressively effaced from the Sri Lankan cricket records, and the subsequent completion of the search by his son Garfield (an alter ego of the novelist Shehan Karunatilaka himself) brings us face to face with issues of politics, ethnicity, language and religion on a strife-torn island,” she says. “But it’s in some ways a more engaging, more positive book than Naipaul’s.”

Chinaman was something of a DIY project. In 2008, its manuscript won the Gratiaen Prize — founded by Ondaatje in 1993 from the proceeds of his Booker for The English Patient, the prize is awarded annually to the best work of English literature by a resident of Sri Lanka. It was subsequently self-published, a family affair, with Tennekoon designing the cover and Lalith Karunatilaka doing the illustrations. Only later was it picked up by Random House.

A Sinhala translation in 2015 made Karunatilaka a household name in his native land, and the Booker has only burnished his splendor. Some weeks after he won the Booker, Karunatilaka arrived late to a concert at the Barefoot Garden Café in Colombo. As he made his way through the venue, whispers of “Look, it’s Shehan Karunatilaka!” rippled through the hip Barefoot set.

Performing that evening was a groovy bastard child of baila and Can called Dot Dotay. A funky four-piece outfit that sounds — in Sinhala, Tamil, and English — like a bricolage of ‘Western’ styles strained through the sieve of local island music, their music is oddly reminiscent of the rhythms of Karunatilaka’s literary hybridity and the rootedness of his inclusive imagination. Karunatilaka wears his forebears on his sleeve, and is the only person I have met with near-perfect recall of the collected works of Ira Levin.

Chinaman is “a novel that lays bare the processes of its own writing,” Chaudhuri tells me. “A novel that stares into the abyss of not-writing, of forgetting, of loss, of obliteration. So, it bears comparison, too, with Kundera’s The Book of Laughter and Forgetting.” She points to “the Rushdie-like play on names, especially ones that are invented through amalgamations of existing (famous) ones.” Even the narrator’s name, WG, is an homage to W.G. Grace, cricket’s first global superstar.

Karunatilaka has always admitted to plundering, in particular, Kurt Vonnegut: “The genius I have robbed from the most is, of course, Uncle Kurt,” he wrote in an essay for the Booker website. “WG needed a curmudgeonly tone that was wise, silly, funny and occasionally profound. Who else but Uncle Kurt?” (He struggled for weeks before pinning down what he calls the “drunk uncle” voice. He knew he’d found WG when he started waking up to a drunk uncle holding forth in his head — “Ey putha, let me tell you about that match they fixed in ’89…”).

More Vonnegut loot he has confessed to: 1. “the non-sequitur illustration,” and 2. “the short explanatory chapter.” (He attributes his love of bullet points to the Hollywood screenwriter William Goldman).

While writing Chinaman, Karunatilaka would haunt a Colombo video store called Bollywood. Hidden behind the superhero movies and the latest Hindi blockbusters was a huge stack of foreign films. “They had Fellini, Kurosawa, Bergman, Hitchcock, all the greats,” he recalled. “Their whole back catalogues for 50 rupees.” His cinematic set pieces — the pandemonium at a wedding that is Chinaman’s swinging opener; a suicide bombing at the headquarters of a government death squad that is one of the climaxes of Seven Moons — are all jump cuts and snappy dialogue, aerial shots and zingers.

These days, he ends up watching animated films with his children before bedtime. “You can learn a lot about structure and form from Pixar, men.”

In April 2018, Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack — the sport’s most sacred scripture, published every year since 1864, through two world wars and a global pandemic — decided to drop the word “Chinaman,” because it was “no longer appropriate,” in favor of “slow left-arm wrist-spin.”

In April 2019, Wisden voted Chinaman one of the greatest cricket books ever written.

Cats

“Our immediate predilection,” Eric Rohmer once observed, “tends to be for faces marked with the brand of vice and the neon lights of bars rather than the ones which glow with wholesome sentiments and prairie air.” At the heart of Karunatilaka’s fiction is an abiding love of mystery and crime. He is drawn to ingenious plotting. His labyrinthine yarns wallow in the comforts of generic familiarity even as they blur the boundaries between reality and its other.

“I don’t think Seven Moons is a political book,” he insisted over an afternoon drink in the charming dishabille of a hotel room that housekeeping forgot. “I’m a genre writer.”

A beautiful Taylor guitar with a kente cloth strap was resting by the desk, and a Bluetooth speaker piped out yacht rock from behind the crumpled blankets.

“Well, maybe it is a political book, but it wasn’t intended to be. It was intended to be a murder mystery.” On the nightstand, The 48 Laws of Power by Robert Greene — “hip-hop’s Machiavelli,” Nick Paumgarten called him — soaked mist from an ice bucket. Karunatilaka tapped his desk with a pair of drumsticks.

“I’ve decided to travel with these sticks.” Tap tap. “I’m hoping they’ll help me concentrate.” Tap tap.

The trappings of noir scaffold both Chinaman and Seven Moons: missing persons; detective and sidekick; femmes (et hommes) fatales; corrupt cops; gangsters; voiceovers; moral rot at social, national, and cosmic levels; chronological see-saws; and, especially, shady dealings in dingy bars, a subtext of intoxication — and its dark twin, addiction — rippling through the veins.

He also loves horror (see above: Ira Levin). “I’ve said this before, the first slasher horror was Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None.” An earlier incarnation of Seven Moons, called Chats with the Dead, had a gruesome scene in which the corpses of people murdered by death squads get fed to cats.

“I enjoyed writing that,” he chuckled nervously. The scene was excised in the final version of Seven Moons, but its traces remain in the guise of a metatextual joke about feeding corpses to cats.

“That scene was straight out of my nightmares.”

Karunatilaka does not wish to dwell on cats.

Bars

Karunatilaka left the sticks behind when we went out to lunch at Chung Wah, a 100-year-old Chinese bar in downtown Kolkata where there is no such thing as a casual drinker. “This is just like back in Colombo, men!” Embalmed uncles reminiscent of WG sat staring at empty bottles of beer. “Of course, there they’d all be drinking arrack.”

Arrack (noun): The local arrack was never served. Too lowly. Matured from the toddy of the coconut flower, it was only secured, and surreptitiously at that, for the servants at Christmas and to give the latrine coolie a snort when he came to the gate on New Year’s Day to salaam and ask for baksheesh.

Carl Muller, The Jam Fruit Tree

Like many noir barrooms, the Hotel Leo in The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida is a fatal place, its casino reeking of trauma and the promise of the eternal score. In Chinaman, WG sees Sri Lanka win the 1996 cricket World Cup from a bar near the Moratuwa bus stand — the Kaanuwa in Moratumulla “serves every type of arrack — Pol, Gal, Blue, White, Old, Old Reserve, Double Distilled, Extra Special — to every type of customer.” At the back door of the Neptune Casino, said to be in the author’s own neighborhood, WG and Ari are refused Old Reserve as they place illegal bets on Cup games.

After the Second World War, wrote Carl Muller, arrack “was no longer infra-dig.” Virtually unknown outside Sri Lanka, Muller is probably the greatest influence on Karunatilaka’s ear for voices. Follow the thread of the Lankan literary tradition of ironic satire and generational chronicle and you invariably end at Carl Muller’s door. A Burgher (like Ondaatje) with a gimlet eye and a flair for vibrant dialogue, Muller’s literary world is exuberant, bursting like an overripe watermelon with an uncontainable lust for life. Muller does for Burghers what Jorge Amado did for Bahians — he expresses their great loves and their reckless disdain, their sacred acts and their moments of profanity, their marvelous reality with its juice sucked dry. “When you read Muller,” Karunatilaka’s brother Lalith told me softly, “it’s like you’re seeing us for the first time.”

Karunatilaka readily admits his debt. “Just as Kurt Cobain convinced me I should play guitar,” he wrote last year in The Guardian, “Uncle Carl told me that it was OK to write like a Sri Lankan person speaks.” Muller’s footprints are all over Karunatilaka’s work, from narrative cadences and everyday lilts of dialogue to the mixing of fact and fiction. “This,” wrote Muller in The Jam Fruit Tree, the first book of his Burgher trilogy, “is a work of ‘fictional-fact’ or ‘factual-fiction’”— a statement that could as easily be about Karunatilaka’s postmodern fabulizing. “The fact of the fiction must be recorded…and the fact suitably fictionalized. I hope the reader understands, because I cannot get the real grasp of it myself!”

Muller’s world of devil-may-care Burghers comes tinged with sadness and regret, even great tragedy (in his sleepy, colonial Sri Lanka, babies can get run over by trains and children abused for years). But his is the long view; his ironic tone and cosmic perspectives render life in its most joyous Technicolor detail. Karunatilaka has inherited this lightness of touch, and Muller’s brio snorts through his stuff. A brawl at a birthday party in The Jam Fruit Tree is echoed in the wedding punch-up in Chinaman. In the latter, a disagreement about a cricketer leads to fisticuffs; in the former, the fault lies in the arrack.

At the bar, Karunatilaka unerringly ordered Old Monk, a rum many would swear is independent India’s greatest gift to civilization. “This,” he said between mouthfuls of chili pork and shrimp rice, “is the best meal I’ve eaten in a month.”

The Circus

Karunatilaka has become a fixture at literary gatherings around the world, where he looks like he’d rather be anywhere else. Nothing but gracious when fans come running for an autograph or a selfie, he still looks uncomfortable with the whole business of being famous: less charismatic frontman, more diffident bass player. (Which makes sense, seeing as he’s played bass for several bands over the years, from Alice Dali and Independent Square to, most recently, the trip-hop psychonauts Powercut Circus). Outside the Victoria Memorial — the gigantic marble monument to the first Empress of India that was playing host to the literary festival Karunatilaka had come to Kolkata for — he seemed genuinely surprised to find himself staring down at unsuspecting passers-by. “Wow, I’m on a billboard!”

The ramshackle cabins inside Chung Wah are named after classics of Bangla literature and utilized frequently by canoodling couples. Our cabin — Chokher Bali, after the 1903 novel by Rabindranath Tagore — had a noisy fan and terrible acoustics. This was a problem, because Karunatilaka wanted to catch a live stream from the lit fest we had ducked out of — a conversation featuring the winners of the 2022 International Booker: Geetanjali Shree, who wrote the remarkable Hindi novel Ret Samadhi, and Daisy Rockwell (granddaughter of one Norman), who translated it equally remarkably as Tomb of Sand.

To a writer accustomed to juggling spinning plates, tinkering comes naturally. There is something delicate about Shehan Karunatilaka, in the little gestures he makes while picking up keys or turning on switches, or the way he negotiates slipstreams as he walks. No wonder his plots are ticking time bombs made of gold filigree. Even his sub-plots have B-stories, matryoshka dolls of nested tales whose bellies churn with a sense of the ridiculous, sculpted from what his compatriot Andrew Fidel Fernando calls “the pain that is the right of every domiciled Sri Lankan.”

In our cabin, Karunatilaka set about constructing a Rube Goldberg amplification system. Glasses of rum were downed rapidly and set on their sides, at precise angles to each other, and a phone propped up at their mouths. More glasses beyond, to chock the resonators from rolling off the table. Sound fixed, he listened attentively and applauded intermittently.

“So, this is what I regret about this whole circus that I’m part of now — no time to read, no time to write. That’s really the game, right?” Since winning the Booker, he has traipsed from Kerala to Karachi, via Dhaka, Kolkata, Delhi, Jaipur and Hong Kong. He conducted a masterclass in Marrakesh. Damon Galgut, the South African novelist who won the Booker the year before, told him he wouldn’t write a word for months to come, and he better get used to it.

“There are too many lit fests these days, and they’re much more professional,” Sarnath Banerjee told me on the phone from Berlin, where he lives and makes comic books. Banerjee befriended Karunatilaka at the Galle Literary Festival almost 15 years ago, where they bonded over nightly drinking sessions. “We were young, we’d mess about, wander the streets, make friends. Nowadays, everyone’s more interested in soft networking.”

In the wake of Chinaman, Karunatilaka would attend lit fests unobtrusively and infrequently. Often slotted into panels on sports literature, he shared many a stage with athletes who’d recently written autobiographies. The Booker has transformed him from novelty act to headliner. He is expected at every book signing and every official dinner (“boozy affairs,” he lamented, recalling several hangovers). He is tired of the ubiquitous five-star hotel food. He even blames the prize for ferrying him back to a cigarette habit. “This scene,” he sighed, “is quite relentless.”

“This is the life of a Booker, men,” he said back at his hotel. “I spend my days answering emails.” He looked at his screen, momentarily confused by something in his inbox.

“Oh, of course, I have an investment adviser now!”

Even as he professes antipathy, Karunatilaka admits these are “First-World Booker-winning problems.” One evening, after a lit fest dinner, he surrendered his room to gatecrashers for an impromptu afterparty. Putatively tottering Indian writers, a dapper Colombian desperate to dance, and at least one Pulitzer winner well on their way to intemperance took over the playlist and the minibar. Karunatilaka had already changed into his nightclothes; in T-shirt and sarong, threatening to throw everyone out at midnight, sharp, he could have passed for any number of marauding trishaw drivers or rampaging uncles from the pages of his own books.

Ambushed by the unceasing tentacles of the circus, Shehan Karunatilaka looks most comfortable when he’s getting ready for bed.

Cheat Sheet

Banerjee speaks of Karunatilaka with the familiarity of friends who do not need to text to remain close. To him, this Booker feels exceptional. “Shehan isn’t trying to explain our world to the West,” Banerjee says, referring to the Orientalist expectations the Global North often harbors towards literature from South Asia. “He’s not writing cinnamon-scented papaya literature. He’s writing for his neighbors. He’s writing for us.”

“The Eurocentric basis of seeing the world,” wrote the Kenyan intellectual Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, “has often meant marginalizing into the periphery that which comes from the rest of the world.” After Chats with the Dead, Seven Moons’ previous avatar, was published in India in 2020, it was deemed too “Sri Lankan” for publication in the West.

“The UK agent could not sell it,” Karunatilaka shrugged. “You know — ‘This is difficult, the Sri Lankan political situation is confusing, this afterlife will be alien to Western readers.’ It was quite demoralizing after all that.” He seemed to have recited this litany before.

“Then I found Sort of Books. They did the Rough Guides, you remember?”

The influential indie British publishing house started by the husband-wife duo of Natania Jansz and Mark Ellingham insisted on some revisions, but otherwise went along with what Banerjee calls “Shehan’s stubbornness to not kowtow to the West.” Of course, certain socio-political intricacies of what Maali Almeida calls “this isle of secrets” had to be clarified. A cheat sheet for the uninitiated, in the form of a letter to “a young American journo confused by Lanka’s abbreviations,” had already appeared in the opening pages of Chats with the Dead; listing the many belligerents and bullies of the beeshana kalaya — Sri Lanka’s ‘time of great fear’ — it was pared down to bullet points in Seven Moons. The rules for the afterlife were spelled out.

“Kinda like Chinaman, you remember?” Karunatilaka pointed out. “The first 50 pages were for readers who know nothing about cricket.” Chinaman was scattered with clever exposition, via lists of cricketers, details from (fictional) documentaries, and Lalith Karunatilaka’s explanatory illustrations — limpid drawings of wickets and bats, carrom flicks and floaters, and even Mathew’s magical realist masterpiece, the double bounce, “the greatest ball ever invented.”

As a publisher advises WG’s son Garfield — near the end of Chinaman, when, in a metafictional sleight of hand, the story you have been reading turns into the book you are holding — “If you want international, Mr. Karunasena, you need to work.”

“I wrote this book for you,” Karunatilaka said in Sinhala near the end of his Booker acceptance speech. “Today, many people in Sri Lanka are suffering, and I have no tools to ease their grievances. However, let us embrace this victory and go on to win the T20 World Cup, because … why not?”

The emcee inside the Roundhouse in London, where the ceremony was taking place, interrupted. In deference to the arcane scheduling practices of BBC Radio 4, she tried to rush him to the end. Karunatilaka continued undaunted.

“Let’s share our stories with each other,” he said, this time in Tamil. “Let’s keep telling our stories.”

Below the stage, ushers and waiters whooped.

Ghosts

“Sri Lanka is a country of forgetting,” Lalith Karunatilaka explained. “It’s important he spoke in all three languages.”

The business of state and the social fabric of Sri Lankan affairs in general are shrouded in a tension of unresolved violence belying the island’s peaceful exterior and its natural beauty. Instead, there is a pervasive sense of guilt coated by a collective apathy born of the effort to forget. Unpunished murderers in palm-fringed villages share the streets with the families of their victims, and have done so for decades.

Gordon Weiss, The Cage: The Fight for Sri Lanka and the Last Days of the Tamil Tigers

Considering the cultural cornucopia it springs from, Karunatilaka’s penchant for polyphony makes sense. For centuries, Ceylon was a confusion of tongues, a genuine melting pot separated from the enormous Indian landmass by the thin sliver of the Palk Strait. Sinhalese Buddhists comprise the vast majority of the population; Tamil Hindus are the largest minority; Malays and Moors often speak Tamil but are staunchly Muslim. “They say that wind brought the Portuguese,” Karunatilaka wrote in a short story called ‘The Colonials,’ “and greed brought the Dutch.” Not wanting to pass up a good pillaging, the British colonized Ceylon in the early 19th century and administered it from Madras (now Chennai). The successful Burgher community, Christian, of mixed European and Sri Lankan descent and now mainly expatriate, spoke their own idiosyncratic patois of English with a smattering of Sinhala. All this on a landmass the size of West Virginia.

As recently as 600 years ago, you could walk from the south-eastern tip of Tamil Nadu in India to what is now Sri Lanka’s Northern Province, across a trail of limestone shoals called Adam’s Bridge (in the Islamic tradition, the first exile from the Garden of Eden fell close by) or Ram Setu (in the Hindu tradition, an army of monkeys built the bridge to allow the god Ram to go rescue his wife from the kingdom of the demon-king Ravana). Stripped to its essence, this is the modern Sri Lankan dialectic: Paradise, or demon kingdom?

Unlike India or Pakistan’s blood-soaked decoupling from the British crown, Ceylon (it has been called Sri Lanka only since 1972) became independent in a manner “so bland,” wrote K. M. De Silva in A History of Sri Lanka, “as to be virtually imperceptible to those not directly involved.” Oxbridge types in suits met in boardrooms and agreed on terms.

Envisioned by its first prime minister, D.S. Senanayake, as a multiracial secular democracy, the lure of communalist politics proved too strong for future leaders. Within months of being elected on a tide of rising Sinhalese nationalism built on linguistic chauvinism, Prime Minister Solomon Bandaranaike — who could barely speak Sinhala — enacted, to great public approval, the Sinhala Only Act. The Act formalized the bureaucratic exclusion of Tamils, a quarter of the population at the time, and became a touchstone for the escalating tone of both Sinhalese and Tamil nationalisms.

Hundreds died in anti-Tamil pogroms after the Act was passed in 1956; over the next two decades, the body count swelled as civil liberties shrank. In the ’70s, the government of Bandaranaike’s widow and successor, Sirimavo, intensified the toxic emissions of the Act. Desperate, radicalized Tamil youth birthed the LTTE.

The LTTE, or Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, waged a brutal civil war in the north and east of the island for almost three decades in their quest for a separate homeland, Eelam, the Tamil Zion. The Eelam Wars began in 1983, after the horrific events of Black July — a week of government-orchestrated pogroms that resulted in between 1,000 and 3,000 dead and 150,000 people becoming homeless overnight, almost all of them Tamil (“If you wake a sleeping lion,” the remorseless minister in charge of death squads in Seven Moons says, in a chilling echo of President Jayawardene’s statement after the riots, “it will maul you”).

The war ended in 2009 when the Tamil Tigers made their last stand on a desolate spit of land on the northeastern coast of the island. Along with the remaining Tigers, snared in the siege were 330,000 Tamil civilians. As the army squeezed the Cage, its relentless bombardment killed and maimed thousands of children and their families, ending only with the discovery of the corpse of Tiger supremo Velupillai Prabhakaran.

The Eelam Wars claimed over 100,000 Sri Lankan lives. Tens, maybe even hundreds, of thousands more were wounded or raped.

In his Booker speech, Karunatilaka wished for a Sri Lanka in which Seven Moons might one day be found in the fantasy section of a bookshop, “next to the dragons and unicorns,” not “mistaken for realism or political satire.” To a country riven by linguistic nationalism, he gave familial love in three tongues.

Equally significantly, the Booker arrived on the heels of the Aragalaya, the mass protests of July 2022 that dethroned the once-invincible Rajapaksa clan (in 2009, after his brother Gotabaya, then defense secretary, had decimated the Tigers, Sri Lankan president Mahinda Rajapaksa was variously anointed, by the leading Buddhist chapters, as the Universally Glorious Overlord of the Sinhalese, Heroic Warrior Overlord of Lanka, and Monarchical Emperor of the Glorious Land of Buddhism). Powercuts, that feature of Sri Lankan life that, in Chinaman, may well be responsible for the obscurity of the titular bowling genius — “The newspapers announce powercuts from 7 to 9 every night for the next two weeks. These powercuts are less than punctual. Some arrive at 6, some well after 8. Some last for 45 minutes, some for three hours” — combined with stampeding inflation to sow what Lalith Karunatilaka called “a civil society we haven’t had in seventy years.” At the ad agency where he is a creative director, employees would show up mainly to strategize for the Aragalaya. Even Karunatilaka’s septuagenarian mother went to the protests.

“And for the first time,” Lalith said, “everything happened in all three languages.”

Karunatilaka had asked a friend to make sure the last bit of his speech was perfect; like most Sinhalese, he cannot speak Tamil. But he is trying to learn with his daughter Luca, who is taught all three languages in school. In some ways, Sri Lanka does seem to be moving on from when he was in high school, only a little older than Luca is now, around the time that the many dismembered morsels of Maali Almeida are thrown into the filthy waters of the Beira (which smells, Maali notes, “like a powerful deity has squatted over it, emptied its bowels in its waters, and forgotten to flush”). Colombo, 1989.

Or Yakas

“The civil war, for all its atrocities, was far away from us,” Lalith Karunatilaka told me. “The JVP insurgency was much scarier.” Once, when the brothers, still children, were visiting family in Kandy — the capital of the ancient mountain kingdom and the heart of Sinhalese political and religious culture, home to the Temple of the Tooth — they saw two corpses by the side of the road. The young men had been ‘necklaced,’ gasoline-drenched rubber tires put around their necks and set alight.

Growing up on a diet of Vietnam war movies, the brothers could have been forgiven for romanticising tanks and soldiers on the streets of Colombo. But charred bodies intruding on a morning walk was a more visceral introduction to the violence of the JVP insurrection.

The true story of the quelling of the Tamil Tigers, the mass killings of civilians in 2009 and the pretence by the government that its victory was bloodless was in effect chronicled and foretold by earlier events written in the blood of the Sinhalese youths killed two decades before. The propensity of the state for extreme violence was a known quantity and was, in a word, predictable.

Gordon Weiss, The Cage: The Fight for Sri Lanka and the Last Days of the Tamil Tigers

Between 1987 and ’90, a violent Marxist insurrection in the south nearly bludgeoned the Sri Lankan state into oblivion. The JVP (Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna, or People’s Liberation Front), notes Maali’s cheat sheet for the American journo, “want to overthrow the capitalist state” and “are willing to murder the working class as they liberate them.” The capitalist state’s retaliation was swift and brutal — the beeshana kalaya saw “the deaths of more than 40,000 (and possibly tens of thousands more) Sinhalese youths,” wrote the former UN official Gordon Weiss, “at the hands of the police, army, and paramilitary death squads.”

Karunatilaka was 15 when the family decided to leave Sri Lanka. He was approaching young adulthood, a condition liable to getting one killed; in the Colombo of the late ’80s, thousands of innocent youths were suspected of being JVP sympathizers and disappeared. Schools would shut frequently, and examinations became unpredictable, so their doctor father decided to transplant the family to the corn-fed sticks of Wanganui, New Zealand. After finishing high school, Karunatilaka studied literature and then business administration at Massey University. “After a year on the dole in Wellington trying to write a novel and failing,” he “decided to go to Colombo and form a rock band.”

In Chinaman, it is in Wanganui that WG’s son Garfield finally locates the elusive Pradeep Mathew; Mathew’s house is even modelled on the Karunatilakas’ own home, “messy but nice.” Karunatilaka mined his Kiwi years for the resolution to his debut novel; in Seven Moons he returns to Colombo, when he left the missing voices behind.

Karunatilaka decided to interview the dead when he was embarking on Chats. Not wanting to write about 2009, he looked back in history, and 1989 stuck out. “I remember, JVP, LTTE, IPKF, wars on three fronts, peace accords, assassinations in the early ’90s — Athulathmudali, Dissanayake, Premadasa, Rajiv Gandhi. I thought ’89 was when that shitstorm really began.”

The theme of Seven Moons, he believes, like the theme of post-war Sri Lanka itself, is forgiveness versus revenge. Two ghosts on different sides of the fence function as its embodiments: Dr. Ranee Sridharan, who wants the dead Almeida to get his ears checked so he can go into the Light, and Sena Pathirana, who wishes to raise a ghostly army that will avenge spilt JVP blood.

Dr. Ranee was modelled on Dr. Rajani Thiranagama, the Tamil doctor and professor of anatomy who co-founded the highly regarded University Teachers for Human Rights in Jaffna. She also co-wrote The Broken Palmyra, “a very disturbing account of what has gone on…in the North of Sri Lanka,” as Brian Seneviratne put it in the foreword, “document[ing] what we have all known, but not had the courage to say — that the civilian population has been cannon fodder in a despicable power struggle.” In September 1989, Dr. Thiranagama was gunned down, possibly by the LTTE, while cycling back from work.

Sena, who shares his last name with Daya Pathirana, the student leader whose murder was one of the first assassinations of the JVP insurrection, was probably inspired by all those idealistic kids who lost their way looking for a better future.

“That’s the real question, right?” Karunatilaka scratched his well-tended beard with painted fingernails as he smoked, “Do we bury the past, or do we dig it up?”

Vans

And among the bombed, the burned and disappeared is you, cause of death as yet undetermined.

Shehan Karunatilaka, The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida

We were in one of Kolkata’s iconic yellow taxis, a rumbling bumblebee of an Ambassador, when Karunatilaka noticed the vans.

“Why are there so many bomb disposal vans? You have many bombings here?”

While there was the odd Tiger bombing in Colombo during the war, it was the vans and Pajeros that people started to fear most. The kind that government death squads tended to disappear young people in. The phenomenon became so prolific that it accrued a nickname — white van syndrome.

“Father, forgive them,” wrote the journalist, poet, and actor Richard de Zoysa in ‘Good Friday, 1975,’ “for I will never.” Using this as its first epigraph, Seven Moons lays out its intertextual cards on the seedy casino table of modern Sri Lankan history. Like Maali Almeida, de Zoysa was a half-Sinhalese, closeted gay man working in the media. He even portrayed — in Lester James Peries’s 1983 film on Sri Lanka’s labor union movement, Yuganthaya — a fervent revolutionary called Malin Kabalana (Maali’s full name is Malinda Albert Kabalana).

On the night of February 18, 1990, de Zoysa — famous, privileged, the scion of two of Colombo’s most influential families — was abducted from his home in a white van. His body was found in the sea the next day. For Colombo’s elite, somewhat sheltered from the war, his death became the originary trauma of the beeshana kalaya.

Georges Perec’s 300-page lipogrammatic novel A Void unfolds without the letter e, which has seemingly been hallucinated out of existence. The absent vowel is a missing cipher for the six million Jews who disappeared in the infernal bellies of death camps. Always on the edge of vanishing, Karunatilaka’s protagonists are supernovas who burn brightest before they explode. Both WG and Maali are dying, one from alcoholism, the other from AIDS. Pradeep Mathew might be one of the greatest cricketers to have ever played, but he is a Tamil man wiped clean from public memory; his is also a disappearance of sorts.

In decades of living in Kolkata, I have hardly ever seen a bomb disposal van. Sharing a taxi with a man who once began a short story with a car bomb rigged to a busload of schoolgirls (‘The Ceylon Islands’), I saw four in one afternoon.

If a writer invokes bombs and imagines disappearances, do the vans start to appear?

Paranoia

The Karunatilakaverse is a web spun from a netherworld Sri Lanka that exists between helplessness and hope. His Colombo is also Macondo or Yoknapatawpha. Characters drift between books. Backstories emerge across books. Protagonists of one book have uncredited cameos in another. Facts bleed into fiction. Read too much of him and reality starts blurring at the edges.

In William Faulkner’s fictional Mississippi county, the blood of the past trickles into the bedrooms of the present. Yoknapatawpha bears the scars of a shameful history of slavery that it has not yet confronted. As in Faulkner, the civil war — or its spectre — is everywhere in Karunatilaka’s barely fictional Colombo.

“Even to talk of war crimes is treasonous,” Karunatilaka told me. “To even request a reckoning, obviously, they say, ‘You’re funded by the diaspora, by the NGOs, by the LTTE.’”

“So, I write about cricketers and ghosts.”

It makes sense that Karunatilaka’s fiction, even as it practises radical empathy, drinks from the gushing well of the paranoid style. In a tradition that stretches from Vonnegut and The Manchurian Candidate to Philip K. Dick and The Truman Show , conspiracies abound in Karunatilaka’s Colombo. As in Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49, quests for people or events may or may not lead to national intrigues. Narrators are unreliable. Around every corner lurks a cosmic joke.

The obsession with texts and textuality that infuses Karunatilaka’s novels coagulates in The Birth Lottery’s ‘Assassin’s Paradise,’ a Borgesian fable constructed from the prefaces of a fictitious book called Assassin’s Paradise by a certain Dr. Ranee Sridharan (Assassin’s Paradise is, of course, a doppelganger of Rajani Thiranagama’s The Broken Palmyra).

A sense of incompleteness and the fear of not remembering — or worse, misremembering — haunt Karunatilaka’s fiction. WG fails to complete his biography of Pradeep Mathew, Maali’s cache of photographs does nothing to end the war. A day will come when the inner void of post-war Sri Lanka is replete with remembering and reconciliation; till then, it will remain a potent space for Karunatilaka’s form of surrealist fantasizing.

When the civil war ended, the government launched a new tourism campaign — Sri Lanka. Small Miracle. Locked away in the attic, Karunatilaka’s stories suggest, is another, equally appropriate tagline — Sri Lanka. Assassin’s Paradise.

“There’s no memorial even now for ’83,” Karunatilaka shook his head. “I mean, 1983! How long ago is that?”

Karunatilaka’s prose transmits the ludicrousness of the late-’80s with spectrometric precision. For years, Indian intelligence had trained and supplied various Tamil separatist groups, including the LTTE, with arms and money. In 1987, after the two countries signed a peace treaty, the IPKF (Indian Peace Keeping Force, known colloquially as the Indian People Killing Force) arrived on the northern shores of the island and turned their weapons on the Tamil Tigers. “Sent by our neighbors to preserve peace,” Maali’s cheat sheet notes, the IPKF “are willing to burn villages to fulfil their mission.”

The peacekeepers wasted little time devolving into an occupying army red in tooth and claw. The IPKF strafed quiet streets from flying gunships, bombed civilian areas, and tortured, raped, disappeared, and slaughtered entire villages (in October 1987, for instance, it massacred scores of patients and staff at the Jaffna Teaching Hospital). Soon, in a twist of geopolitical preposterousness that would not feel out of place in Karunatilaka’s fiction, the Sri Lankan government itself started arming the Tigers in a bid to get the IPKF out. Within months of the Indians withdrawing, the Sri Lankan Army and the LTTE resumed hostilities.

Have the hyperbolic absurdities of his tormented isle sharpened Karunatilaka’s teeth for irony and existential monkeyshine, an island where protesters start shampooing when attacked with water cannons, as they did some months ago at the University of Jaffna? An island where the Tigers and the army declare a ceasefire for the duration of a cricket World Cup? Little wonder that he cocks a snook at people like himself, the English-speaking Colombo elite — like Maali and his two flatmates, his lover DD and DD’s sensitive cousin Jaki, who have had very little skin in the dying game (or even literally at himself as Garfield, WG’s slightly annoying son in Chinaman, who finally gets his father’s book published under the name Shehan Karunatilaka) — as nonchalantly as he skewers the butchers, the bureaucrats and the generals.

As a child, Karunatilaka once crucified his brother Lalith’s teddy bear to a wall; a vengeful Lalith hanged Shehan’s teddy from the living room fan. Perhaps outsized realities provoke exaggerated sublimation.

Poop

Latrine coolie, you ask? Well, yes. In those days many homes had no drainage, sewerage or water service. Not even the best of them. So the lavatories had squatting plates and buckets — and each day around ten a.m. coolies (also called bucket men) would come around with their carts (universally known as shitcarts for want of a simpler name) and carry away the nightsoil. Their visits would scent the air, true, but were they not vital in their service to the community?

Carl Muller, The Jam Fruit Tree

“I’m a huge admirer of your writing,” someone in the audience told Karunatilaka at the lit fest, “I’ve read all of your books.”

“Have you read Where Shall I Poop? My masterpiece.”

For the last few years, Shehan and Lalith Karunatilaka have collaborated on a series of picture books for very young children. Featuring the goofy Baby Baba, who is modelled on Karunatilaka’s son Theo, the books are meant to be used as developmental aids; reading his “masterpiece,” both children and adults can learn of the wondrous defecatory designs of animal life (“Parrotfish poop out fine sand for the ocean/If you burn up cow poop, the mosquitoes need lotion”) while commiserating with Baby Baba (and his parents, for “When Baba’s in the toilet, he causes commotion”). And, in the morality tale of health and hygiene that is Please Don’t Put That In Your Mouth, Baby Baba chomps his way, with toothless, tingly gums, through an increasingly surreal list of objects — “The neighbor’s bull/The almirah/The neighbor’s cart/The palmyrah” — while his long suffering Akki, his older sister (obviously Karunatilaka’s daughter Luca), has to make sure he doesn’t munch on poo.

Like the Choose Your Own Adventure Books he grew up with in his nerdy corner of Colombo, Karunatilaka crafts his children’s stories in a second-person narrative voice, drawing the reader in by putting her in the shoes of an incontinent toddler or a teething baby. In Seven Moons, he uses the same trick with greater guile and far more bile.

In awarding Seven Moons the Booker, the judges singled out “the ambition of its scope and the hilarious audacity of its narrative techniques.” The dead protagonist’s hip bourgeois voice narrates the novel entirely in the second person, a ghostly autodiegetic narrator thrusting his readers into a suffocating sense of identification, a voice brushing frequently against the actual vocalizations of its owner every time we meet him, still breathing, in flashbacks.

The discordance between dialogic and narrative voices creates a uniquely unsettling aural field, like an old gramophone record on which the music wrestles with needle chatter. A limit-noise suffuses Seven Moons — what the French semiotician Roland Barthes called the rustle of language, “[making] audible the very evaporation of sound.” The second-person voice of Maali’s ghost becomes the spectral projection of a collective Sri Lankan haunting.

Hearing the audiobook was a revelation for Karunatilaka, because Shivantha Wijesinha, who narrated it, does different voices for the diegetic words of the still-alive Maali and the metadiegetic voice of his ghost. In a way, the dissonance works as scratches of trauma on narrative vinyl.

Seven Moons started out as Karunatilaka’s attempt at horror, in the vein of his beloved And Then There Were None, a closed circle mystery in which 10 people trapped in a house on a lonely island get knocked off one by one. Even the new Glass Onion, Karunatilaka pointed out, riffs on the same theme.

“So I took this premise, because there was a bunch of aid workers that were killed during the height of the war. Fourteen aid workers, all in their 20s, all Tamil.” (There were actually 17, almost all in their 20s and 30s, 16 Tamils and one Sri Lankan Muslim working for the French NGO Action la Contre Faim. They were summarily shot in August 2006 near the resort city of Trincomalee on the eastern coast, quite possibly by the Sri Lankan Army).

“I don’t know if anyone’s owned up to that,” Karunatilaka sighed. “These were kids going to build fucking toilets for refugees. And they were all executed.”

He insisted on going online to show me their faces.

Karunatilaka decided to borrow the story of the aid workers and transform it into slasher fiction, a gory tale of people dying in a bus. A 300-page draft found its way into the dustbin.

“The only thing that worked in that was a ghost on the bus, a supernatural element I hadn’t planned for,” he recalled, “causing these guys to kill as the bus went along the tsunami-ravaged coast in 2004 … ”

He paused mid-sentence. “Actually, now that I’m telling you this, someone should write this book!”

Even as he abandoned the slasher novel and turned to children’s books and the short stories that would eventually find their way into The Birth Lottery and Other Surprises, Karunatilaka kept thinking about the ghost on the bus. He gravitated towards the idea that perhaps, once we’re dead, all that survives is our internal monologue.

“It’s the voice in my head, men,” he told me soon after we’d seen all those bomb squad vans. “Isn’t the voice in your head in the second person?”

The voice in my head is mainly grunts and mumbles. “Ah, a monosyllabic voice! Lucky you.”

It is “the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself,” Faulkner said while accepting the Nobel Prize, “which alone can make good writing.” At the heart of Karunatilaka’s fiction are the little ripples and eddies, the intimate details of everyday life that build or break the walls between people. WG’s love for his wife, his friendship with Ari, his disintegrating relationship with his son Garfield; Maali’s triangle of love and friendship with DD and Jaki. Cocooned in layers of conspiracy and a dispassionate narrative façade, intimations of humanity are rarely far away. Karunatilaka’s writing is preternaturally biased towards compassion.

We left the bar and joined other ne’er-do-wells on a boat ride in the dark. As the rowboat drifted through the oily waters of the Hooghly — the river that wends along Kolkata’s western rim — the rest of us nattered on, chuckles here, a snatch of the boatman’s song there. Karunatilaka stretched out on the prow and smoked. He caressed the fig trees that bent over the river like old drunks looking for arrack in a dimly lit dive.

The boat finally bumped into the dock, and he stood up. He looked unsure for the briefest of moments, as if wondering whether he could blow off the impending dinner he was expected to star in and float down a river instead.

Turning his back to the water, Shehan Karunatilaka jumped on to dry land and walked off without waiting for his companions. As if he was listening to that voice in his head.

Ey putha, let me tell you about that match they fixed in ’89 …

*The author wishes to thank Ellen Berry — teacher, friend, role model — for her comments on an earlier draft of this piece (and for being fantastic in general).•

Source images courtesy of kjpargeter, freepik, mrsiraphol, and rawpixel via Freepik.com.