In the 1984 novel The Boys on the Rock, by John Fox, a 16-year-old student relays scandalous information about a pair of identical twin brothers on his high school swim team. “I was forever hearing rumors about them being incestuous and things like that from guys who didn’t even know them,” the narrator reports. “They got called pretty insulting things right to their face but they didn’t give a shit.” On this the teenager offers clarification: “I don’t mean they just pretended not to give a shit, I mean they truly did not care what anyone thought about them.”

This passage resurfaced from the depths of my consciousness recently while I read every extant interview with Woody Allen I could get my hands on, though I’m not alluding to sexual innuendo about the director. Yes, Allen did seem oblivious to the uproar that ensued in January 1992 after Mia Farrow — his longtime romantic partner and the star of 13 consecutive films under his direction — discovered in his Manhattan apartment racy photographs of her 21-year-old daughter Soon-Yi Previn, whom Allen later married. Eric Lax, whose updated Conversations with Woody Allen (2009) is the most recent edition of book-length Allen interviews, dealt with the Soon-Yi material previously in the revised 2000 edition of Woody Allen: A Biography. “Woody has a remarkable ability to compartmentalize his life,” Lax wrote then of the custody battle that ensued over Farrow and Allen’s three children. By so saying, Lax seems to have originated what is now the most oft-repeated maxim about the filmmaker: in Woody Allen: A Documentary (2012), the director Robert B. Weide assembled a brief montage of Allen’s friends and colleagues, each repeating the same line about Woody’s ability to compartmentalize his life. All evidence points to Allen similarly taking this compartmentalization approach toward allegations that he sexually molested his and Farrow’s seven-year-old daughter. (After an investigation, the police brought no such charges against the director.) Allen himself explained at the time of his legal wrangling that, in all the months of public and private turmoil (which cost him $7 million in lawyers’ fees alone), he was not distracted for a moment from his creative work. When he informed his friends of this fact, they thought something was wrong with him — that he had a surprising lack of feeling, as Allen phrased it. “But it isn’t so,” the director insisted. “I had the appropriate feeling at the time, but my work is a separate thing.”

Having consulted, in addition to Conversations with Woody Allen, two previous book-length volumes — Woody Allen: A Life by Richard Schickel (2003) and Woody Allen on Woody Allen by Stig Björkman (2005) — and the pieces collected in Woody Allen: Interviews (2006), edited by Robert E. Kapsis and Kathie Coblentz, plus more recent uncollected interviews with the director, I can conclude that Allen likewise treats the public’s response to his movies as something entirely separate from the work itself (and I don’t mean he merely pretends not to give a shit). Neither critical acclaim nor critical dismissal, neither encouragement nor discouragement from a mass audience seems to influence the choices Allen makes when settling on a project, writing the script, shooting and editing its scenes, or releasing the completed film. “I have over the years had to make some kind of pretense of caring,” Allen once admitted. “But the truth of the matter is, I don’t.”

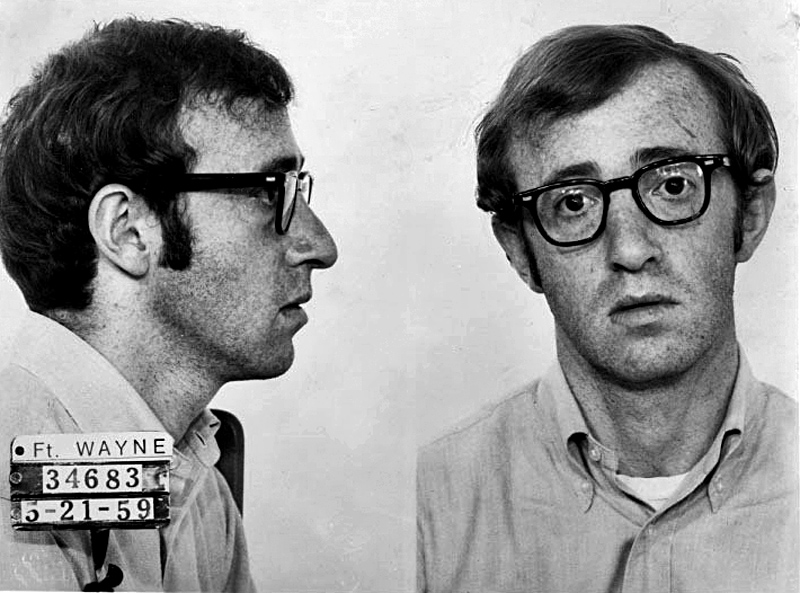

The director has maintained a highly disciplined work schedule since Take the Money and Run premiered in 1969. Over nearly five decades, he has completed one feature film per year. (“His record is astonishing,” Schickel commented, “and quite unmatched by any contemporary American filmmaker.”) The director’s speed of production helps account for his indifference toward the opinions of audience members. I don’t mean to suggest he’s a sloppy craftsman or an uncommitted artist; I mean simply that, at this pace, by the time a movie is released he has other things on his mind. “Tomorrow The Curse of the Jade Scorpion opens,” Allen told Björkman in 2001. “To me that is ancient history. I couldn’t care less. I’ve already finished another movie, and I am working way beyond that.” Regarding his 2008 release, Vicky Cristina Barcelona, he reported, “I’ve already finished the picture with Larry David” — he meant Whatever Works, his 2009 feature and his first Manhattan-based project in five years — “and I’m working on a script for another new film” — 2010’s You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger. “So I have no interest in Vicky Cristina Barcelona.” For the same reason, the director does not keep DVD copies of his old films on hand. “I couldn’t care less about them,” he has insisted. “I did them. It’s like poking around half-eaten slices of pizza. It was last night’s take out — fun last night, but I ate it.”

Allen’s disciplined work routine alone probably can’t account entirely for his blasé attitude. Were he a less prolific director, he might still ignore the public’s response and derive little pleasure from the opportunity to entertain a mass audience. The original title of Annie Hall, after all, was “Anhedonia,” a psychological term referring to the inability of some afflicted persons to experience pleasure. In Conversations with Woody Allen the director told Lax, “Years ago when Manhattan opened in New York I did not go to the premiere at the Ziegfeld Theater and the big party at the Whitney after.” Instead, he got on a plane and flew to Paris. “So people think, He doesn’t care, or He’s too aloof, or He’s snooty or arrogant,” stated Allen, “but . . . that’s not it. It’s not arrogance, it’s more like joylessness. It doesn’t thrill me. It just doesn’t really mean anything.”

The lack of joy derives in part from the low regard in which Allen holds his own work. In 1986 an interviewer asked him, “Which film has been a disappointment to you?” He responded, “I’ve been disappointed uniformly down the line.” To Lax, Allen explained that, after viewing titanic works such as Ingmar Bergman’s Cries and Whispers and The Seventh Seal, he grows depressed. “I see his films and wonder what I’m doing,” the American sighed. “I’m not saying my work is degenerate or insulting to the intelligence,” he once explained, “it’s just less than what I wanted it to be.”

It may seem unfair for Allen to hold his own films to the standards of Bergman’s masterpieces, but the comparison is somewhat apt considering that, when he writes a film script, Allen routinely senses that, finally, he is on the verge of greatness. “I think I’m going to write Citizen Kane every time out of the box,” he told Schickel in 2003. “And then I make the film, and I’m so humiliated by what I see.” That sense of humiliation can reach ludicrous, Kafka-like proportions. “In the case of Manhattan I was so disappointed I didn’t want to open it,” Allen confessed to Björkman. “I wanted to ask United Artists not to release it. I wanted to offer them to make one free movie, if they would just throw it away.”

Still, when pressed Allen will admit to accomplishing pretty much what he set out to do on a few of his films. Stardust Memories, Zelig, The Purple Rose of Cairo, Husbands and Wives, and Match Point get mentioned most often in this regard. “I’ve done some things that are perfectly nice,” he conceded to Schickel. “But I had a much grander conception of where I should end up in the artistic firmament. What has made it doubly poignant for me is that I was never denied the opportunity.” That is, from the start of his film career, this director has demanded and been given final cut and had complete freedom to write and cast his films as he’s seen fit — within the limits of a modest studio budget. When Lax asked whether there was anything liberating about working in London, where the director had shot Match Point, Scoop, and Cassandra’s Dream in three successive summers (2004 to 2006), Allen replied, “It wasn’t liberating. I always feel liberated.” Perhaps uniquely, Woody Allen has enjoyed a 47-year directing career free of interference from studio muckety-mucks like those he satirized in Stardust Memories and Hollywood Ending. “The only thing standing between me and greatness,” he is fond of saying, “is me.”

Entering his 80s, Allen has shown no sign of slowing down his production schedule and no sign that old age or nostalgia has begun to soften his attitude toward last night’s congealed cinematic pizza. But at least now he shows up for the premieres of his movies and even sits for frequent interviews. “I do a little promotion out of loyalty to the money people because I don’t want to be a mean guy,” he explained to Douglas McGrath, Allen’s friend and one-time collaborator (they co-wrote Bullets Over Broadway). “But I have no interest in the picture.”

Of course promotional work on a movie, if done grudgingly, may actually prove counter-productive since its ostensible purpose is to sell the product and burnish the image of the celebrity involved. But Allen takes no heed of this. “A lot of people find your filmmaking revitalized after moving out of New York,” offered Colin Covert during an August 2008 interview for the Minneapolis Star-Tribune timed to the release of Vicky Cristina Barcelona. “I don’t know what they’re talking about,” the director snapped back. “I think my films are the same as they were when I was in New York. People like to talk, and they hear someone say something, and then they repeat it mindlessly and it means nothing.” If Woody Allen offends a journalist or puts off thousands of newspaper readers with his impatient responses, this is of no apparent concern to him. He is, in a sense, the anti-Zelig, the exact opposite of the character described by Michiko Kakutani as being “so insecure, so anxious to be liked, that he literally assumes the personality and physical mien of anyone around him.” Woody Allen cares little whether large or small crowds turn out for his films or whether those people who do turn out are predisposed to enjoy themselves or express hostility. “If people love the film, then that is delightful,” Allen once allowed. “If they don’t like it, then . . . hmm . . . that’s tough. They’re either completely right in not liking it, or they’re quite brilliant and they see flaws in it that I never saw, or they’re philistines and they don’t get it and I was right. But it’s irrelevant because I don’t really know or care.”

Perhaps Allen acts indifferent to the success of his movies because he can. His iconic status as a director and his films’ relatively small budgets together ensure that he will always find financing for his next project. Soon after releasing the chamber drama September in 1987 to the weakest box office response of his career, Allen finished editing a second drama, Another Woman, which also underperformed. At the time Allen assured his biographer it was immaterial whether Another Woman replicated the success of Hannah and Her Sisters or tanked like September. “I’m still going to make my next movie,” he explained. “I’m not in that position where the bottom’s going to drop out.”

Two decades later the conversation with Lax again turned to the subject of financing. “Do you know yet where you’re going to shoot your next film?” Lax inquired of Allen as he edited Scoop in 2005.

“No, I don’t know yet,” the director replied. “I’m waiting to find out, and that will dictate what I write.”

“What will determine it?” Lax asked.

“It will be dictated by the origin of the money,” he explained. “If the British people give us the money to make the film, the condition usually is that we shoot it there.” (Indeed his subsequent film, Cassandra’s Dream, was filmed in London with British financing.) “If it’s a French co-production, then we’ll shoot it in France” — as he did Midnight in Paris. “Sometimes you raise the money and they don’t care where you shoot it, in which case, I don’t know — I might shoot it here.” He meant in New York City. “But the ideas that I have in my notes are quite different,” claimed the director.

I have an idea for Barcelona. I have an idea for Paris. I have an idea for London. [He is laughing now.] I have an idea for New York. But they’re all different. And I’m waiting to pounce. I’d like to pounce tomorrow, but I probably won’t know for about four weeks, in which time I’ll finish Scoop and just noodle. I mean, I could write a play, or maybe try and write a piece for The New Yorker. I’ll fill the time.

Unlike the appropriately named Harry Bloch, the troubled writer he played in Deconstructing Harry, Allen has, to his own amusement, a plethora of story options available at all times. “Do you worry about the sources of your inspiration drying up?” he was asked in 1980. “Not at all,” he replied. “Quite the opposite in fact. I worry about not having enough time to develop the ideas that I have. I wish I could press a button and have a film come out because I have ideas for six or seven movies in the future. I just can’t do them fast enough.” And therein lies the central question of Woody Allen’s puzzling career: Why does a writer-director who is unconcerned about the reception to his films — and who considers his work to be mediocre at best — continue in a dedicated fashion to tap the wellspring of ideas from his imagination? Why bother?

“I’m not a workaholic,” he has blatantly insisted, attempting to dispel one rumor. “I work very casually. I’m lazy. Films are not my first priority.” In fact he considers his output to be unexceptional. “The truth is, if you write a little bit every day, you get a lot accomplished,” he explained to Lax. Likewise the rigors of filming a movie are overstated. “You always hear that making a film a year is like building the Guggenheim Museum every year,” he told Covert. “It’s not. Maybe for someone like Steven Spielberg, who makes a film for $150 million, and it takes him a long time because it’s a mammoth film with hundreds of extras and special effects. If you’re making Batman or something, it’s a big deal. But I don’t make those kinds of films.” Writing and directing nearly 50 movies in as many years, though — that is a remarkable feat by any measure. “Why do you make so many movies?” Jean-Luc Godard, another prolific director, asked Allen in 1986. “I don’t know what else to do,” was his reply. “I finish a movie and then I have another idea. So, that’s what I do for a living: I make movies.”

Any literate person possessing the most cursory familiarity with Woody Allen’s films (and, in turn, with his quirks and preoccupations) will not be surprised to hear that the director is motivated in part by his obsession with mortality and the transience of human existence. “Death is a no-win proposition,” he assured McGrath. “Because you know what happens? You die. I’m not a religious person, so you die, and then you disintegrate in one way or another — either you’re cremated or you decompose — and you’re gone. That’s it. There’s no other at bat. It’s one strike, and you’re out.” Allen is under no delusion that the world is in need of every narrative idea he can squeeze out in the time allotted to him in this life, nor does he imagine that an artistic legacy benefits him in any way. (“It doesn’t profit Shakespeare one iota that his plays have lived on after him,” he told Björkman.) Rather, he explains, his filmmaking routine helps keep him sane — “to the degree that I’m sane.” When Lax asked the artist directly how he avoids succumbing to the despair that drives Geraldine Page’s character in Interiors to suicide, he replied, “Over the years I’ve worked out a million little strategies to get around it: working strategies and relationship strategies and distraction strategies.” Chief among those strategies is the tactic of spending nine months of every year — every year, without a break — writing, directing, and editing a feature film, even as he also readied the musical stage adaptation of Bullets Over Broadway for its 2014 premiere and the 2016 television series Crisis in Six Scenes for streaming through Amazon Studios. He explained the situation to Schickel thus: “It’s like a patient in an institution who they give basket weaving to, or finger painting, because it makes him feel better.” And he assured Lax, “Busywork at the sanitarium keeps the inmates occupied and tranquil.”

This path to tranquility was discovered by the director inadvertently. He initially pursued fame and adulation like any girl-starved Brooklynite in his teens and 20s would, but the spoils of artistic success disappointed him. “After my first couple of films, I saw I had a good time making them,” Allen recalled, but “once they came out, the fact that many people loved them didn’t mean anything to me.” (Nor did it make him any more attractive to women, he claims.) Moreover, he expected that artistic failure would prove demoralizing when it finally arrived, but he reported, “I found it didn’t hurt that much at all.” Neither success nor failure, then, has affected his basic well-being to a significant degree. Releasing a film does little to rectify the real problems in life, he insists. Only obsessive tinkering with a narrative provides real relief. “It helps mitigate against giving oneself over to the horrid gloom of reality,” he has concluded.

Of course, Allen’s self-prescribed mental-health cure has been supplemented by sessions with an analyst, as autobiographical films such as Annie Hall and Anything Else imply. In a September 2008 interview for New York magazine, Adam Moss ribbed the director for his reliance on a coping method that seems to have failed him miserably. “As the world’s most famous analysand,” Moss asked, “can you say whether you think analysis works?”

“People always tease me,” the director responded. “They say, look at you, you went for so much psychoanalysis and you’re so neurotic, you wind up marrying a girl so much younger than you. You don’t like to go through tunnels, you don’t like to stand near the drain in the shower.” Viewers of Wild Man Blues, Barbara Kopple’s 1997 documentary film about Allen’s New Orleans-style jazz band, will have no difficulty citing additional examples of the director’s many neuroses and phobias: he’s deeply claustrophobic, he’s obsessed with germs, he requires two separate hotel bathrooms when traveling so his toiletries remain unmolested. (“I’m crazy,” he told Kopple.) “But I could also say to them, I’ve had a very productive life,” Allen reasoned further. “I’ve worked very hard, I’ve never fallen prey to depression. I’m not sure I could have done all of that without being in psychoanalysis” — or, it seems, without his relentless filmmaking schedule. “People would say to me, oh, it’s just a crutch,” the director continued. “And I would say, yes. It’s a crutch, and exactly what I need at this point in my life is a crutch.”

His employing two sturdy crutches — a heavy schedule of analysis and a similar schedule of filmmaking busywork — would seem directly to contradict the main theme of The Purple Rose of Cairo, one of the few films Allen seems truly pleased with making. In that movie Mia Farrow’s character, Cecilia, forfeits a fantasy world offered by a glittering Hollywood movie and its male lead (magically come to life) and returns instead to the reality of a sadistic husband in Depression-era New Jersey. “As Woody says, she made the right choice,” Schickel summed up: “one cannot live sanely within a fantasy world.”

But if Woody Allen is the anti-Zelig for not caring in the least whether he is liked by others, he seems also to be the anti-Cecilia for not squarely facing reality. “Bliss comes from the success of denial,” he tells anyone who will listen. In 1994 he repeated to McGrath that the only purpose of making a film, for him, was the diversion of doing it. (“I’m so involved figuring out the second act, I don’t have to think about life’s terrible anxieties.”) He then uncharacteristically shifted his focus to the needs of those on the receiving end of his filmmaking habit — the moviegoers — suggesting that his disciplined and even obsessive efforts to produce movies may in the end constitute an act of generosity. Without becoming zealously evangelical about the tonic of denial, he told McGrath that every film he directs offers an opportunity to people who might otherwise not have the talent to make films, write novels, or even finger paint and basket weave. The value one of his films may have for them, he explained, is that it becomes their distraction. •

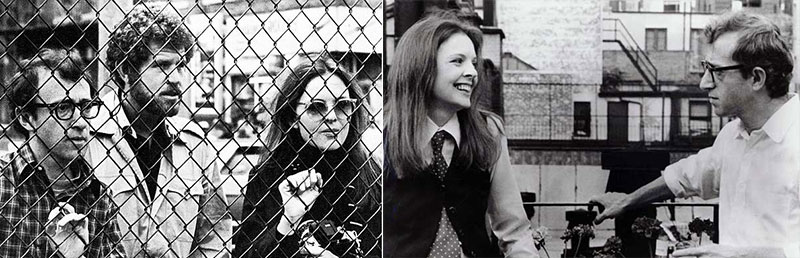

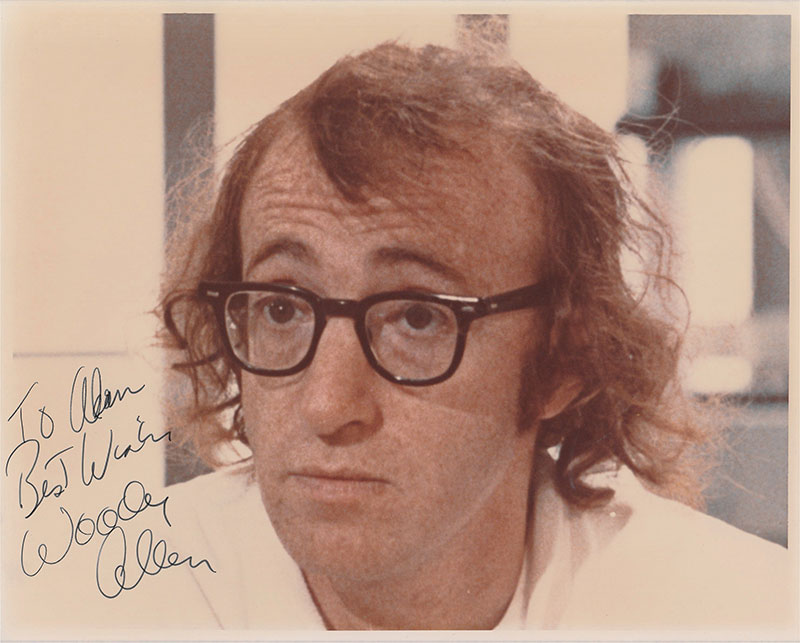

Feature image courtesy of Thomas Hawk via Flickr. Article photos courtesy of the Lester Glassner Colection via Wikimedia Commons and drmvm1, angela, Aurora, and Alan Light via Flickr (Creative Commons).