Like many high school swains — or would-be swains — I was accustomed to being jolted in affairs of the heart. Allowing that we have not experienced parental or sibling death, substance abuse, abandonment — which is to say, tragedy — by that point, these teenage blows are often when life starts to discomfit us. They make us doubt who we are, commencing a lifelong battering of queries as to whether we are good enough.

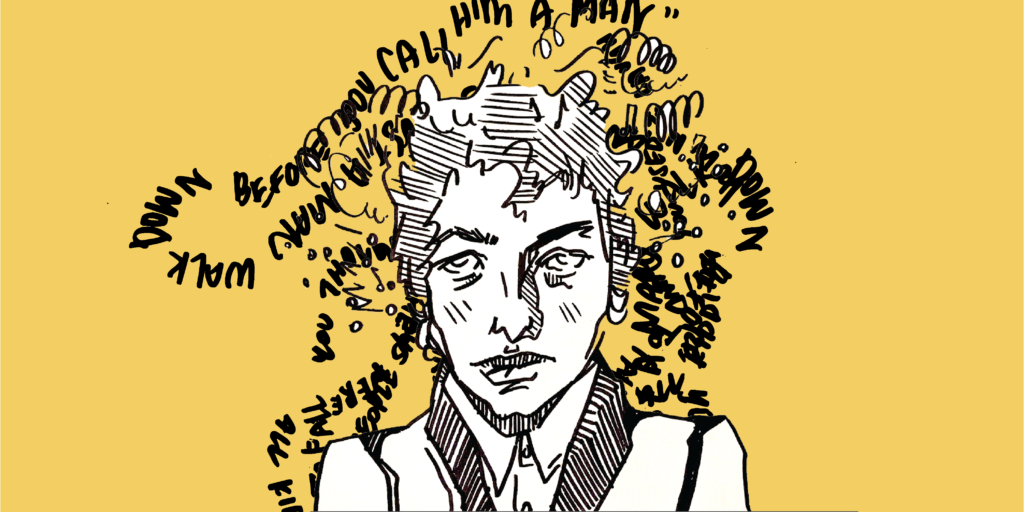

As with a lot of people, my wound-licking process involved copious amounts of music. I’d roll around town at night in my early driving days listening to Bob Dylan albums. You want the rock and roll, the volume, at that age, which meant heavy doses of 1965’s Highway 61 Revisited and Mike Bloomfield’s screaming lead guitar on the tape deck. But for all of the decibel-laden blues-rock harrumphing, it was the album’s closing number, “Desolation Row,” that hit me as what I now think of like the chaos assimilator, a work of art both prolix and assured that helps you wrest back a little control in your own life.

The extended song has always served this function in the Dylan canon, continuing to the present day with his latest effort in the long-form medium, the 17-minute “Murder Most Foul,” released — in the dead of night in the States — as people across the world hunkered down in their homes during the age of COVID-19. By my count, Dylan has four long songs, from different phases of his career, sharing some traits, differing considerably from others, but executing a similar and invaluable purpose.

“Desolation Row” was entry number one, coming at the close of Dylan’s first all-out electric album, though you won’t detect much electricity with this 11 and a half minute-long number. The texture is that of an English pastoral, with Nashville guitarist Charlie McCoy somehow making his guitar fills resonate with the quality of a lute as Dylan weaves what’s tantamount to a huge, mishmash of a gossip narrative, involving characters from literature, history, the Bible.

T.S. Eliot throws down with Ezra Pound on a ship, Einstein finds it useful to dress up as Robin Hood, Casanova has his ego assuaged by sycophants. You think, “what the hell is going on here?” until the end when the references flake away and it’s time to get real, as the singer describes receiving a letter from a past lover. It’s not a Dear John note, but rather one of those missives, after the fact, saying how great life is for that other person, with false concern for the individual they no longer know. At which point the singer reveals that rather than read this rigmarole and treat it seriously, he made up what we’ve just heard instead, changing the names, a form of amusement, before he returns to his life. He has better things to do, and sometimes that’s to simply let the creativity roll.

That impressed me as a way to handle someone else’s passive-aggressiveness. The next year, to close Blonde on Blonde, Dylan recorded “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands,” which is almost the same length as “Desolation Row,” a coppery affair, like some citrine, glimmering meadow aside a wheat field. It’s a love note that gains power via repetition of the phrase, “My warehouse eyes / My Arabian drums,” which is the respective manner of the orb and make of instrument that the singer requires to process, store, and signal his depth of feeling for the song’s subject. This is new to him, but right: natural order after a period of unnaturalness in the form of a staid life, lacking for wonder. Dylan thinks humans can be better than that and owe themselves more — but not without the work of the required various voyages of discovery. Helps to have your notes ready to go, too.

As we will see especially with “Murder Most Foul,” these are list songs, in one way. We’ve all been there. Life is out of control, your anxiety is kicking up, so what do you do? You pull out the paper — or the app on your phone— and you make that to-do list. Maybe you make a list of items you need to think about. Factors for a decision that has to be made. You might make lists off of the lists. I do. I am nothing without my lists, whether that is in life or in my work.

In 1997, having seemingly been written off as a past master who was no longer a perpetual one, Dylan returned armed for artistic battle with Time Out of Mind, a record that was going to close with — you guessed it — one of his long cuts, in the 16-and-a-half minute-long “Highlands,” a vignette song employing an old Scottish melody with an overlaid timbre of American blues, about a man drifting through daily minutiae — a conversation with a waitress in a café, for instance, a debate about whether he reads enough feminist literature — trying to locate himself again, realizing in what is tantamount to a process of comprehension that his essence had not wandered as far afield as he thought it had.

It isn’t easy to do this kind of thing and not have it be a repetitive grind. The musical backing doesn’t change a ton — in fact, there’s not a single modulation in these performances. They are not jams — that backing needs to be arresting from the jump and remain so. Musicality in the vocal is crucial — an excitement of forms of phrasing — because the voice becomes the central instrument. Yes, rock and roll songs usually feature someone singing, but the vocal is often not the go-to, the “main” instrument — think of, say, “Satisfaction” by the Rolling Stones, where the guitar riff, the backbeat of the drums, and Mick Jagger’s voice have a sort of triple billing. These Dylan long cuts, though, live or die with that vocal. You need a clever lyric, which builds upon itself. That is, one line suggests a form of wordplay, a line that follows must deliver the goods while retaining and developing the sense, the thrust of the story, the vignette, the poem, the series of incidences that will form a totality.

You get a good idea of Dylan’s methodology on “Murder Most Foul,” because he name-checks artists who helped him in this development along these lines. The title refers to John F. Kennedy’s assassination in Dallas in November 1963, an event sufficiently seismic that in a decade rammed with such events, it puts all others in the shade as obscured, lesser, even if some were not. For Americans, Kennedy’s demise was akin to that familial-style death of which we were talking earlier, minus a person having lost their dad or sister, or been kicked out on the streets. Let’s call it crossover death.

Right-back in his earliest days of 1961-62, Dylan was a master of the talking blues. He got a lot of that from Woody Guthrie, but more so yet from Charlie Patton and Son House, bluesmen for whom songs were books, unfolding stories that were going to take as long as they took. They weren’t adhering to the three-minute confines of songwriting, save when the realities of recording technology imposed such dictates upon them. Dylan is a blues singer more than a folk singer, always was, despite all of the permutations of his voice. The Dylan of Nashville Skyline doesn’t sing in the same tone or register as the Dylan of the Basement Tapes sessions as the Dylan of Blood on the Tracks, but he does sing with blues inflection. Talking blues inflection.

On “Murder Most Foul,” Dylan speaks to us — in our homes — as much as he sings to us. The Kennedy killing is the touchstone, but it’s also a stand-in. This isn’t Dylan making light of an epochal murder — it’s not, as he might say, for nothing, that he crowns the song with a bit of Shakespearean regicide. Kennedy wasn’t formally a king, but so far as Americana went in the 1960s — and really since, with all things Kennedy — yes, he kind of was. The title is sourced from Hamlet, one of our best ghost stories, when the murdered father pipes in to inform his son about who did him in. The revelation — this being Shakespeare — reveals what a doozy of unnatural order with which we’re contending. The restoration of natural order ain’t coming so easy. There will be work involved.

As I listen to “Murder Most Foul,” I’m struck by the backing, which features a violin — further, a soft, gauzy violin, which isn’t the normal voicing for the instrument. Violins are the guitars of the classical world — well, excepting actual guitars when they do put in an appearance in classical repertory — in how they cut into you. They are the volume merchants, the commentating instrumental voice.

Dylan uses them decoratively here, as a means of ushering in his own voice, which is, fittingly, violin-like. Or maybe fiddle-esque, since we’re talking America, where fiddle music was so central to celebrations going back to the earliest days of the Republic. The Kennedy assassination is thematically ambulatory; that is, the song is less about that day in Dallas than it is tragedy’s ability to make all of us miasmic. A lump. Insensate. I would say that the quotidian tragedy is the norm of our days now. Not the killings, the pandemics, but rather myriad forms of 21st-century life that facilitate our cultural and intellectual devolution to the point that someone like Dylan can drop a song called “Murder Most Foul” on the world, and I would wager that few people had a clue that the phrase could be traced to Shakespeare.

Dylan is not a social media guy. When Little Richard died — and Dylan had no bigger hero as a boy in Hibbing, Minnesota, for it was Little Richard, more than anyone, he wished to be — the songwriter posted a moving tribute, but Dylan was always a liker, if you will, rather than a courter of likes. He’s one of those people — Stephen King is another, even if I don’t think much of his formal work — who likes cool things, the things that can get inside your head and heart space and alter how you perceive and interact with friends, family, colleagues, community, the world.

We are less and less adroit at locating these people and work now because they don’t tend to all of a sudden show up in front of our faces. You have to look for them. When I first got into the Beatles, I needed to know who had first done “Anna (Go to Him),” which moved me to the deepest rhythm and blues I would ever encounter in the work of Arthur Alexander. But I had to go there — it didn’t come to me. Dylan wants you to go to wherever “there” might be for you.

He sets up the song as though the music were a kinescope — a sonic film of a film that only existed in the Zapruder snippet. In a musical form that centered on finding control — which is different than invented, biased notions of proclaiming “my truth” — Dylan has a panacea. We might say that he uses a veritable Pangea of pop culture to induce the panacea. There used to be a phrase where one would “turn on” someone else to something else. It began as a bit of drug-speak that came to mean, “I will introduce you to something special, you’re going to love this,” which you would, in turn, wish to share with someone else.

We’ve lost that in our culture now, with its emphasis on disposability, the ephemeral. We are going to forget, via a process of unseeing, more than we know or will learn. What we encounter does not matter as much that we did encounter it, however fleetingly. The fact that something goes viral has been ascribed greater value than what that thing actually is. And again, we don’t go looking.

The bardic narrator of “Murder Most Foul” is the sage invoker of what it means to look — not just to find, and to share, but for the process of discovery. As such, he brainstorms where you might start, which is where he started. The song becomes a tour of an aesthetic hagiography that’s a sort of living museum. I say living museum because this isn’t Dylan merely suggesting, “Hey, go play some tunes by the Who, screen a Clark Gable film, find about what Guitar Slim was all about,” though he does say that as well. Truth is an objective concept that we invariably seek to personalize. The singer of this song catches himself in the attempt, something we rarely do anymore, which costs us as a society. Objectivity is lost, and feelings becoming the new, ruling demigod, with the inescapable problem being that reality is always, ultimately, going to win, to pull rank and take precedence. Just like time. That’s the nature of both, regardless of your “feelz.”

Jazz musicians have a term called contrafact, which I’ve always loved. It’s part of their workaday reality, a musical form that parallels the reality of life. A performer like Charlie Parker, in the bop heyday of the mid-1940s, would take a tune—or, rather, the chord changes of a given tune — and write a new song atop that tune/changes. Call it a version of the old song, and a new song all at once. “Murder Most Foul” is a spiritual contrafact of “Highlands,” the quest-song, with sage advice to boot, advising you to play this, watch that, read this, discover, devour, share. Charlie Parker is there, Elvis’s filthiest blues cut in “One Night of Sin,” Buster Keaton, Jesus, Stevie Nicks, the Everly Brothers.

He interpolates the references with commentary on Kennedy’s killing, which remain factually accurate, and certainly clever — the observation he was killed in front of scores of people and no one saw a thing, as one example — but as the pulse of the song extends, is “taken out” to use another phrase of jazz musicians — and this is an exceedingly jazzy performance — Kennedy becomes a suggestive device, a harkening that there is always a lot happening right in front of us that we don’t see. Can the artists Dylan enumerate help us see better? Of course. Can being the kind of person who looks, who seeks to share, connect, and turn on and be turned on help? Even more so. But the two ride together.

The Beatles — who pop up in the song — had a sea of holes, Dylan has a sea of references. The Kennedy symbol is the bathysphere that allows for what we now so often call the deep dive, but this dive is singular. His singing pace never varies, which astounds me. I don’t know the exact specs, but I’d be shocked if this was an overdubbed affair. My guess is he just did the vocal in the studio, however many cracks he needed. Billie Holiday was this way, especially near the end of her truncated life. She pushed no tempos faster than they need to go.

I call it cognizance singing — it’s total control. Singers are human, they get caught up in their message, the emotion of their lines, and obviously the longer the song, the more chances you have to go awry and push when you shouldn’t. Dylan catalogues and delineates how he has come by the truth he knows, or a part of it, anyway — these artists were his vehicles to the truth. Find yours, he says. But maybe try some of these. They don’t have to be singers or writers; they can be illuminating emotions that have been tucked aside, the honest appraisal in front of the telltale mirror.

But back to that contrafact. The third to last reference in the song, in its penultimate line, goes, “Play ‘Love Me or Leave Me’ by the great Bud Powell.” The pianist was the towering figure on that instrument of the bop era, and would later wax an album of Charlie Parker tunes that might be the best tribute record anyone has ever made. One for the shortlist, definitely. But the thing is, in this tabulation of historical accuracies, be they regarding Kennedy, art, film, music, literature, TV, there’s not a single half-truth, save in this final reference, because Powell never had such a song.

He had a contrafact with his own “Get It,” which is built off of the “Love Me or Leave Me” changes. Dylan knows this. He’s not erring in his Bud Powell history, putting forward fake news about old bop pianists. We see the elasticity of personal feeling, though, and also memory, a cultural call to duty to recognize our tendency to blur and conflate. The final line features a shout out to the “Star-Spangled Banner,” its title now changed to replace “Star-Spangled” with “Blood-Stained” (a word contrafact), before a final directive — play all of this, yes, but also play this very song, “Murder Most Foul.”

Dylan is not self-aggrandizing. He hasn’t reason to be. But he does realize the utility of the “turn on,” the crucial vitality of the effort. As with “Desolation Row,” the names of “Murder Most Foul” are less important than why they are deployed as they are. The functionality of the process. The search. The seeing of what is in plain view, if you can teach yourself how to see it. Otherwise, we’re talking a kind of murder of the self most foul, which is why Hamlet’s dad had such a need to intercede on his son’s behalf, the same as Dylan has on ours. •