Growing up, it seemed like we went to a different National Park every summer. A few weeks after school let out, my parents would pack up our station wagon and, over the years, check them off the list. Yellowstone, the Grand Canyon, Mount Rushmore — all places that, as new inhabitants of the capacious idea known as America, they knew they were supposed to have seen and documented with photographic proof.

Stops on the road were seldom, and as vegetarians, we ate what we always ate: rice, dal, dahi, and roti that my mother had dutifully packed in a stackable metal tiffin box the night before. At a shaded rest area, she would expertly unpackage the contents, doling out scoops of lentils onto Styrofoam plates. In the afternoons, after we had been driving for most of the day and the heat threatened to overwhelm our car’s A/C, my dad would pull in to a gas station so that he and my mom could sip cups of tea from a Thermos.

We’d stay the night at distant relatives’ houses in Texas and Oklahoma, where dinner was served in the same floral-patterned Corning dishes that we used at home. And just like at home, Hindu iconography dotted the walls — a painting of blue-skinned Krishna holding a flute; a batik print of Ganesh and his unperturbed gaze. In the morning we’d set off again, bhajans droning out of the tape deck.

•

Maybe my parents could sense the rays of adolescent angst emanating from the back seat. Or maybe they just knew that they didn’t have long with all of us under the same roof. Either way, it was during those long days in the car, when the sun was at its highest, the air shimmering above the Midwestern expanse, that my dad would turn to my brother and me in the backseat and ask: “Taco Bell?”

Even my dad — Dad, who ran three miles a day, whose topspin remained unreturnable well into his 50s — couldn’t resist the alchemy of spices and seasoning contained within Taco Bell’s refried beans.

Oh, those beans. Much has been made of the affinity that Indian-Americans have for Taco Bell. I’m here to tell you that it’s all true. It’s easy to forget, now that lab-grown meat substitutes have become nearly ubiquitous, but at one point in the not-so-distant past, fast food vegetarian offerings were limited to items on the outer margins of the menu board, in what felt like afterthoughts. I recall at least one instance in which we ate, as a family, a meal of French fries and rectangular apple pies in cardboard sleeves. Except at Taco Bell — by simply uttering the magic phrase “sub beef for bean” (over the years, I’d even start to place my order using the Taco Bell cashier’s same keyboard syntax: -BF/+BN, “minus beef, plus bean”), you could have access to nearly any item on the menu.

A gooey, cheesy gordita crunch, with its impossibly pillowy outer crust? No problem. A chalupa supreme, its molten contents ensconced in a flaky golden pancake? Why not make it two?

But the affinity runs deeper, beyond one of mere convenience or access to variety. In America, to be “from” somewhere else is not simply to have a name that, in the words of the critic Hanif Abduraqib, doesn’t “fit comfortably in other people’s mouths.” It is to be in 1st grade and, when everyone else is eating hot dogs, be given a bun filled with only ketchup. It is to eat your lunch in the school bathroom, acutely aware of how last night’s leftovers might make the cafeteria smell.

To be able to take part in something as simple as ordering from a drive-through and eating in the car is to make the chasm between worlds a little bit smaller, to escape the bardo of hyphenation, to plant yourself firmly, if temporarily, on the side of American-ness.

•

Fast-forward a few years. I’ve left North Carolina for college in the Northeast, which, as a self-serious high schooler, is all I had ever wanted to do — to experience bitter cold, to smoke cigarettes, and pretend to understand Murakami. And of course, to be able to walk into a room full of people and know, even before entering, that there would be others that looked like me.

Here, finally, would be kids that would get it, that would know what it meant to occupy the strange valence of first generation immigranthood without the need for overwrought explanation or justification.

But these, as it turns out, weren’t kids from small towns in the South. They were from New Jersey’s wealthy enclaves, the sons and daughters of surgeons and financiers, not middle managers. They studied accounting and, during campus recruiting fairs, dropped their resumes at the Goldman booth, the contours of their futures already confidently outlined. At parties, as I glumly stared into my Solo cup, they’d talk about classes they were taking, using terms like “process management” and “retail supply chains.”

And yet, miraculously, there was Taco Bell — that great equalizer, cutting across social strata like few other things could (hip-hop, maybe? We did, after all, all know the words to Biggie’s “Juicy” and were communally excited when Jay-Z collaborated with Panjabi MC). But to sit on the floor of a rowhouse with a bunch of other Brown kids, several Supreme Soft Taco Party Packs opened between us, my lack of familiarity with the language of finance, my clumsiness with Microsoft Excel (or, perhaps in starker terms, my lack of a BMW) was, momentarily, at least, a more porous barrier.

•

After graduating, for no good reason, in particular, it seemed — other than having been raised in the crucible of overbearing Indian parenting — I moved back home to start medical school. My own future, I was disappointed to realize, was turning out to be just as pre-ordained. Before long, I was mired in the inanity of memorizing the Krebs cycle. I found myself spending a lot of time wishing I had had enough of a spine to ignore filial piety and join the Peace Corps.

My medical school classmates, on the other hand, all seemed so certain of their decision, taking an almost perverse joy in spending hours at the library. They, too, were mostly the kids of doctors. They fluently spoke the argot of medicine and easily donned its sacred objects, unironically showing off family heirlooms like their parents’ stethoscopes from their own medical school days, freshly engraved with a new set of initials.

There are a lot of clichés about medical school, most of them untrue — but I can at least confirm the veracity of one, that studying medicine is like “drinking from a firehose.” It would only be years later, after I had actually begun to practice medicine, that I’d learn just how ludicrous this mode of instruction was — that, as it turns out, being a good doctor has very little to do with whether one can name the specific enzyme involved in adding a phosphate group to a certain tyrosine moiety. But at the age of 21? Multiple-choice exams, which came in a steady onslaught every two weeks, felt momentous, as though lives truly did hang in the balance.

My own apartment, spare though it was, had always been out of the question as a place to study. With no couch or desk, I’d just end up laying in bed, staring at the ceiling and wondering what my life’s alternate timeline, the one where I didn’t go to medical school and accepted that unpaid magazine internship, might have looked like. Coffee shops, after I realized what a steady flux of four-dollar lattes was doing to my meager bank balance, quickly became out of the question.

•

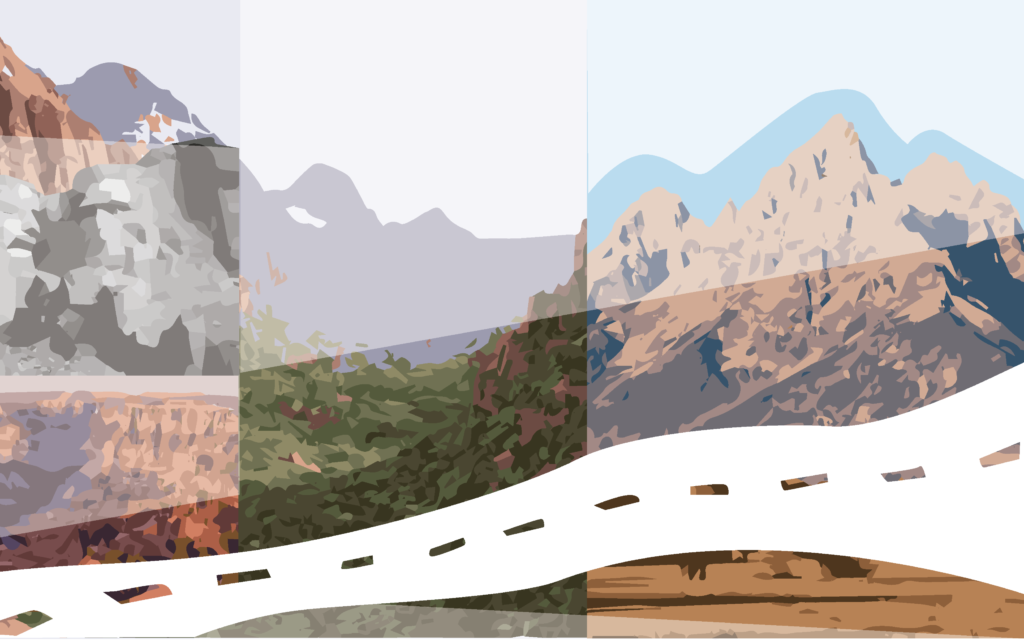

And so it came to pass that I’d spend hours at the Taco Bell a few miles from my apartment. Around this time, the fast-food chain began to rebrand itself, slowly replacing the locations that I had grown up with — the ones that were meant to evoke the humble architecture of the American Southwest, with terra cotta roofs and gently arched doorways — with sleeker ones that vaguely resembled nightclubs or airport lounges: clean lines, sectional seating, large LCD menus, and Wi-Fi. I’d prop myself up in the corner and study renal sodium handling, pausing only to refill my cup of water and occasionally buy a bean and cheese burrito, taking care to squirt tangy Fire sauce onto each bite.

Another truism about medical school, one that they don’t tell you about: you will, during those four years, be the loneliest you have ever been. You will be short with your parents on the phone, becoming increasingly impatient with your father’s desultory descriptions of his day. You will let voicemails from old friends pile up — until they no longer do. You will realize that those parts of you that could have, at any point in the past, been considered even remotely interesting have all been subsumed under the singular ideology of getting into a reputable residency.

I’m not going to tell you that Taco Bell (store #29364, Durham, NC) magically conferred upon me a sense of belonging. But in the same way that the photojournalist Chris Arnade has described certain McDonald’s franchises as de facto community centers, especially to the residents of America’s moribund Rust Belt, this Taco Bell did give me something — a place to be left alone, where I could spend hours, with a menu that I could recite by heart. And among the young families eating dinner, dudes in their 20s watching movies on their phones and sipping giant fountain drinks, old men asleep in the corner, I, hunched over my laptop, did feel an odd comfort, a sense that, “belonging” aside, I was at least still a part of this world.

•

About six months into my residency, when I was living in New York City, that’s when it happened. My mom still can’t bring herself to call it by its name, preferring instead to refer to it (on those rare instances where she elects to talk about it at all) as “The Event” — a name so bland and nondescript that it only makes it seem more ominous, more baleful. For my part, I’ll call it what it is. Why else did I end up becoming a cardiologist, after all? Largely, I realize now, to be able to give a name to that which couldn’t be named, to master a lexicon that — if nothing else — would at least allow me to limn, in cold, clinical detail, the exact manner in which our lives changed.

•

“Vulnerable plaques.” That’s what they’re called. Those gobs of cholesterol, inflammatory cells, and free radicals that sit within the walls of our heart’s arteries, waiting to rupture and expose their toxic innards to our bloodstream. Our bodies, in their exuberance at recognizing these foreign contents, send hordes of cells and protein to this breach, forming a clot. The result, colloquially, the “widowmaker;” clinically, ST-elevation myocardial infarction, myocardial necrosis, ventricular tachycardia.

We all have them, these plaques. Autopsies of GIs shipped back en masse from the jungles of Vietnam demonstrated fatty streaks, the precursors to these plaques, even at 19. But why, in some, do they remain quiescent, and in others, detonate without warning? What makes them “vulnerable,” exactly? And to what? Perhaps the signs had been there all along — looking back, my brother and I can both recall when we first were able to beat my dad in a game of tennis, a sport he always seemed to play with such fluid ease (and in stark contrast to his usual stiff demeanor). Or there was the time that he was helping me move into my first apartment in New York, carrying one end of an Ikea futon down E. 88th street, only to pause and heavily lean against a brownstone, his face drained of color.

The poet Elizabeth Alexander writes of her late husband Ficre, an Eritrean refugee who died suddenly of a massive heart attack at the age of 50, that “the heart is a metaphor and the heart is real. Sustained strain can break the heart and people who walk to freedom often carry that strain for the rest of their lives, invisible, but ever-present.”

My dad, like the thousands of Indian nationals that had been granted J-1 and H1-B visas who arrived in waves in the ’70s, wasn’t fleeing war or deprivation. But I can’t help but note the parallels. He carried with him the trauma that all immigrants carry — of crossing an ocean, of leaving kith and kin, of arriving to this new world only to exist at its outer margins — an un-belonging which I now realize that, even though I’m a generation removed, is inscribed within me.

•

My dad barely survived his heart attack. Afterward, he retreated even further into asceticism, becoming so fanatical about physical activity that on trips home, getting in late at night, I’d find him pacing the living room for hours on end. He renounced anything that might have tasted or felt good, including his treat to himself, the occasional trip to Taco Bell for a side of refried beans. My mother (likely, it always seemed to me, out of intense guilt at not being able to stop what none of us could have foreseen) became a maniacal caretaker and stripped her pantry to its bare essentials: no ghee, brown instead of basmati rice, jars of Folger’s instant coffee that had been repurposed into storage containers for dried legumes.

One of the many problems with real life is that it doesn’t seem to want to abide by the genre conventions of writing workshops. Great, illogical leaps; twists of fate that, in the hands of a screenwriter, would be derided as being too on-the-nose and riddled with cliché — they happen all the time.

To wit: I am the cardiologist who overlooked the signs of his own father’s impending massive heart attack. In spending most of my 20s and 30s learning the practice of medicine — cramming for meaningless exams, half-finishing meaningless research projects, working 36-hour shifts — I had also unquestioningly swallowed modernity’s most pernicious myth: that, with the engine of scientific progress on our side, we were well on our way toward eliminating the random cruelty of a universe that could result in the type of statistical anomaly that my dad, on a cold morning in January, instantly became.

•

I don’t go to Taco Bell much anymore. People hear this, and it makes sense to them. Of course you don’t, they say. You’re a cardiologist. That stuff’ll kill you. And look what happened to your dad.

It’s upon hearing this last bit that the bile rises in my throat and my pulse starts pounding in my ears. The uniquely American conceit of prizing the individual above the collective extends to the way we treat the ill, blaming them for their own condition. What did Sontag say? That biomedical illness tends to be interpreted as psychological? People are, she writes, “encouraged to believe that they get sick because they (unconsciously) want to.”

Sontag was, of course, speaking of her own cancer, not heart disease. But as a cardiologist, I think of her words often — and the fact that, despite what you’ve likely been led to believe, it’s the vanishingly small minority of people who develop a cardiovascular illness due to some discrete “choice.” There are always causes that are more proximate, more complex than simply the inability to “eat right” and exercise, root causes that are embedded in the invisible lattice of structures that govern our everyday lives.

So even in cases like my dad’s, perhaps in an effort to make sense out of entropy, people will offer up their own unsolicited, individualized explanations, ranging from the race-essentialist (Indians—as though this term represented some meaningful category — they’ll have you know, are exquisitely sensitive to the deleterious effects of the “Western diet”) to the overtly Orientalist (he must have been “stressed” — but wait, wasn’t he a regular practitioner of yoga?).

•

My own son is 19 months old, perhaps still too young to truly appreciate the bliss that comes with that first bite of a Doritos Locos Cool Ranch Taco with beans subbed for beef. What he does love, though, is his grandfather, my dad, his aba. One of our favorite pastimes is looking at photographs together and spotting people he knows. As someone who, for a long time, felt little attachment even toward his friends’ children, I can’t begin to describe the feeling I get seeing my son clap his hands gleefully and point at his grandfather.

There is one picture in particular that we look at a lot — of the four of us, my parents, my brother, and I, from one of those interminable road trips. In it, we are in Alaska, outside Denali National Park — or maybe it was the Tetons? The exact location doesn’t matter. Everyone looks happy, even my dad, who has that look on his face that, to the novice observer, resembles a scowl, but that I immediately recognize as a smile. My mom, wearing high-waisted jeans, sits with her arm around my brother. I am at a remove toward the edge of the frame, wearing flannel and sporting an ersatz Kurt Cobain haircut. The Barthes-ian studium of the photo is clear — our family, one of the last times we were all together, and years before my dad’s body would betray him.

But there is something else that holds my gaze when I look at the photo — what Barthes would call the punctum — something that only I would notice. We are sitting on the edge of a flowerbed, but behind it is a beige stucco wall, and just entering the top of the photo are the eaves of a terra cotta roof. To the left, an arched window. Look even closer still, and you can see a paper bag next to me, on which there is, barely discernible, a bell. •