October 15th, 2017 12:50 a.m.

During the dark morning hours, the time when my eyes are cloudy and my muscles ache, I worry about losing you in space. My gut lurches with that feeling people get when they’re holding a helium balloon and lose their grip — there’s no more control of that umbilical string, and what was once an extension of them drifts into the atmosphere. In the glow of street light coming through my blinds, I imagine you floating toward the stars. It’s a slow ascension, yet you’re just out of reach. Your crown catches moonlight and shines like the long hairs I pull from my clothes, the ones that clog our bathtub and live in between the fibers of everything.

After I turned off your brain for the first time, I noticed how the buzzing of electricity that’s normally in the room ceased to insense me. I felt stillness. It was like the green desolation that lingers after heavy rain, when the quiet is fragrant. You had pleaded in the way you always do before bedtime. But the back of my eyes felt like fire. I was close to chewing through my tongue.

“You’ve gotta get some sleep,” I begged. “Now go lay down. Please.” You cried. You stomped your foot, beat your head with an open palm, and squalled loud enough for the neighbors to hear. I wanted to yell at you. I wanted to make you understand that you don’t work or pay bills. You don’t, you can’t, appreciate the moments of quiet when your eyes are closed and your racing mind has slowed. At least, I didn’t think you could. I think I’ve just tried to convince myself.

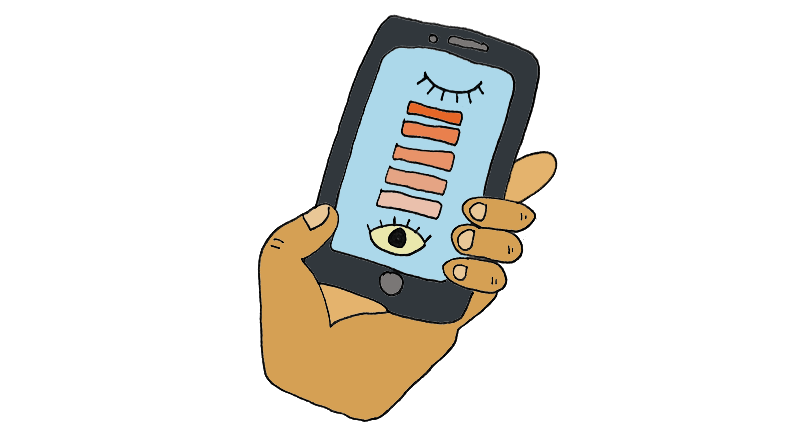

After I shut your bedroom door, you threw something across the room. It could have been a toy. You could’ve broken your tiny knuckles against the wall. Yet I pulled my phone from my pocket and tapped on Absolution, the app that allows me to choose the intensity and duration of your sleep. The workday would start in just four short hours and I needed only a few of those for myself.

I slowly slid my thumb across the phone. It was as easy as dimming the lights. And after only a moment, your crying abruptly ceased. That was it. There wasn’t any kind of dramatic shift. Any guilt I had was muted. You just slept as if a switch had been struck. I remember carefully opening the door and feeling my way into your dark room. I checked your breathing. I didn’t trust the app to monitor your vitals, so I held my finger under your nose, my hand to your heart. It was then my composure started to give and I slipped into your bed. Even though you were right there, I felt alone.

The exam room was small, from what I remember. I couldn’t help but feel anxious despite the toys on the floor, the dinosaur patterned rug and colorful abacus, the exam table shaped to look like a smiling sloth. The doctor drilled us with questions and it felt like my oxygen was being cut short. Why had I agreed to the meeting?

“Melatonin?” she asked. Harper kept busy by roaming the room. Her hands were held out in a kind of open embrace as she touched and mouthed anything she could reach.

“Yeah,” her mom responded, “It doesn’t work.”

“It’s a natural hormone that regulates the sleep-wake cycle. Good for falling asleep, not so good for staying asleep.”

“It’s worked some,” I said, “but not a lot.”

“How many milligrams?”

“I dunno” — I pretended to think — “Five, maybe ten.” The doctor pursed her lips.

“And your daughter’s previous physician — did he prescribe anything like Zoloft or Clonidine?”

My ex-wife shifted in her seat, “Right, she has taken that. She just won’t stay asleep. It’s a persistent issue.” They both looked to me. I nodded my head.

“She’s been frequently getting up in the middle of the night?” the doctor reiterated.

“Yeah,” we both echoed. It was the first time we’d agreed in a while.

“And the previous medications haven’t sustained sleep, even at larger doses?” Harper approached the doctor and poked her face. The woman playfully returned the gesture. She started to say something but stopped.

“Sweetheart,” I pleaded, half-apologizing, half-dreading the exchange, secretly solaced by the fact that someone else was recognizing our plight without establishing blame, and could see Harper’s eyes plagued by dark craters of sleeplessness. They made her look alien and much older than five.

As she continued talking, I wanted to point out that, at first, I’d never agreed to give Harper drugs. Rather, I’d told her mom I’d given them to Harper on our nights together, that I’d crushed them into powder and laced her yogurt. I was angry about the whole ordeal, and that made it easy to invent the story. But Harper’s sleeplessness persisted. It became a weight, which loomed over my evening. I dreaded nine, ten, 11 o’clock, the jumping and guttural screeches when I tried to get her to bed. I prayed away being punched in the jaw when Harper lashed out. I closed my eyes and wished not to be kicked in the back as I lay in her bed and tried to apply pressure to all the right muscles. I never wanted to give her anything for fear it’d steal away a piece of her, some kind of faculty I’d never noticed or taken for granted. I’d taken anti-depressants a few years prior. They made me somnambulic and too agreeable. But without sleep, Harper was a shell of a kid. Eventually, I bought a mortar and pestle. I stocked up on yogurt and I stopped lying.

“Does she often feel tired, fatigued, or sleepy during the daytime?” the doctor asked, tablet in hand. I could see colorful screens in the reflection of her glasses.

“Yeah, we all do,” my ex-wife joked.

“Has she been treated for high blood pressure?”

“No.”

“Low iron?”

“Yes.”

“Does she snore? Do she use electronic devices before bed?” Once, when I asked Harper why she couldn’t sleep, she bit my nose.

“What’s her age?”

“Six,” I said, “Isn’t that on your form?”

“Does she experience anxiety, nervousness, sadness or depression?”

“Madness?” I asked.

“Sadness.”

“I don’t think so,” her mom answered.

The doctor mumbled and typed, “Seizures?”

“No.”

“Has she been tested for Fragile X?”

“What’s that?”

“Are there nighttime choking spells?”

“Jesus, no.”

“What’s her neck circumference? Is she active? Does she experience headaches, facial or jaw pain, clicking, or teeth grinding? Has there been a loss in the family?

I looked to my ex-wife, but she wasn’t there anymore. I felt the specter of Harper’s hand on my arm.

Has there been a loss in the family? CPAP device? Do you feel like you’re choking? Have you lost your appetite? Has there been a loss in the family? Have you become maladaptive? Has your environment become hostile? I ticked my finger and tapped my toes. Why are you divorced? What did you do wrong? Have you owned up to your mistakes? Do you want to drive into oncoming traffic? Do you question your sanity and ability to properly care for your child? Has there been a loss in the family?

“A loss in the family?” I sprang back to attention.

“Yes?”

“Yeah,” I replied, “my dad. And the divorce.” The doctor gave a sympathetic smile.

“These adjustments can be hard on kids. You both seem like you’re doing your best.”

There was a short silence. I didn’t make eye contact with anyone. “How long has it been since the divorce?”

“Seven, eight months,” I replied.

“Almost a year,” my ex-wife corrected me, “So, what else is there?” Harper climbed onto my lap and stood, keeping her balance by fisting my hair. She was so heavy.

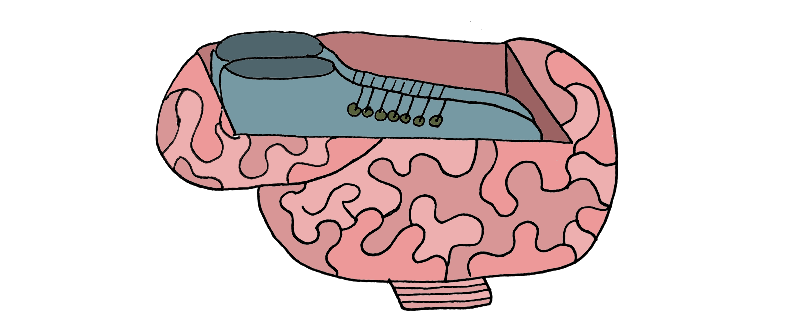

“Well, with your consent,” the doctor began, taking off her glasses, “we’ll be injecting a device that’s called ‘Reliqua’ on the market. It’s not FDA approved, but I’ve seen it do some amazing things for our kiddos. Basically, through a small syringe, we inject a chip into the bloodstream and navigate it to the hypothalamus. Small electrical currents will control Harper’s hyperactivity.”

I stiffened. “Small electrical currents?”

“No more than a pinprick. Nothing she can feel. And then, through an app called ‘Absolution,’ you can induce narcolepsy. It can be as strong or weak as needed — but only enough to lure her into a complete sleep. The app shouldn’t allow you to make any quick, dramatic shifts.”

“Are you sure there’s no pain?” my ex-wife asked, “How could she tell us?” The doctor set down her tablet.

“Again, nothing she will feel. It’s like a mild sedative. We could order the preliminary blood work this afternoon.”

Harper picked up something from the floor and put it in her mouth. I asked her to spit it out and she swallowed, laughed. She climbed into her mom’s lap and began kissing her chin. It occurred to me that maybe I’m the problem. Maybe this new custody agreement wouldn’t work out.

“I’d suggest keeping a sleep diary,” the doctor continued. “Track her hours asleep. Make note of when she wakes and how she behaves while awake. We can meet again once the results from the blood work come in.”

I tried to return the sympathetic smile.

September 21st, 2017 7:00 a.m.

Last night, I dreamed you fell down a manhole. It was in the middle of your bedroom floor, one of those big copper-colored circles you see in the street. For some reason, there was no cover and you just walked in. I called to you, tried to use my phone’s flashlight app to peer into the darkness, but it was just too deep.

The first thing I thought to do was call the police, but they took two days to get back to me. In that time, I carried on by going to work, watching TV, all the while wringing my hands in fear you were hurt. I called to you each evening. I just stared into the musty darkness and screamed. There wasn’t an answer. I waited anxiously for someone to take action.

When I finally decided to do something, I realized just how deep the hole was. It was a recess that stretched well into the earth, maybe miles. I began climbing using steel rungs attached to the wall. I didn’t get very far until I became paralyzed with the thought that the ladder could buckle.

There’s a gap. I don’t know how, but my brothers, your uncles, were suddenly all gathered together to help. They brought some of their friends. We decided to feed a long rope down the hole, so as I climbed, I could grab onto something. I didn’t get down many rungs until I became frightened and climbed back up. All I could feel was space around me. The air was dark matter. The entrance was only a pinpoint of light shining as small as a faraway star. And then I heard a buzzing — an alarm or a rushing of water — swirling black throngs of bees.

I climbed back up and rechecked the rope. My brothers and their friends were gone. And then, up from the hole, you came. You climbed out all by yourself. You were dirty, but otherwise happy. We rejoiced and cheered and you seemed okay. I didn’t think to reposition the manhole cover, so while my back was turned, you jumped off of your bed and fell down once again.

Without thinking, I climbed in an untethered frenzy, missing rungs and hitting the walls of a narrow brick tunnel to hell. But the hole wasn’t nearly as deep as I feared. I touched ground and noticed how rust ran down the walls of a small, subterranean sewer. Water rushed under my feet as I straddled a concrete ledge. You lay there with a wound on your head. Blood trickled toward your temple. You seemed to be fluttering in and out of consciousness. But rather than picking you up, I helped you stand. I supported you on your climb. You were halfway up the ladder when I woke.

Am I really trying my best?

I should have felt more anxious the first time I left Harper completely alone.

After my marriage, planning to go on a date or meet up with friends felt impossible. When it happened, I always kept my phone at a moment’s reach. The volume was always up. I was in a kind of disassociated attendance during those cold evenings in Chicago when the split was definite and the divorce impending. I don’t know what I could have done for Harper from so far away.

As my time with Harper — what would later be written into custody agreements — became routine, my trips to Chicago increased. Over the better part of five months I drove eight hours round trip to live in a world that I missed but was never mine. Harper couldn’t have called me. She couldn’t have told me something was wrong. I didn’t necessarily fear that my wife couldn’t handle our child. It was an instinctual worry, a hold over from the days when Harper was a baby and her grandparents kept her overnight. That was when her mom and I tried to remember why we’d gotten together in the first place. Why had we become parents so young? Maybe I projected my feelings about her onto the state of things. I think the guilt of being away from Harper should have made me more anxious.

At any moment, I was prepared for a dramatic phone call. I’d receive news Harper had choked in her sleep, or she’d run away from home again. Imagining this fate for her wasn’t some sick fascination. It was a coping mechanism, I think, something all parents do to emotionally prepare themselves if something horrible were to ever happen. I’d rehearse my response, how I’d keep it cool and ask for factual information — what hospital — how long — how quickly I could hop in my car and make it to the interstate. Throughout dinner, movies, concerts, walks downtown, I’d look at my phone and count the minutes until it was time to return home and relieve my wife. We’d switch places so she could also go out and reclaim pieces of her youth that had been given away.

Why would I leave a toddler by herself? After the divorce and the implant, I didn’t need to worry anymore — at least not in the way that I used to worry. It’d been a few weeks since the immediate side effects of the Reliqua had worn off. Harper was no longer agitated or disoriented in her waking hours. Her mom was giving me good reports from school. There were no more tummy aches in the evenings and her meltdowns were at a minimum. With improved sleep, I even started to see her speech progress. It was slow — sand escaping parted fingers, but we were beginning to speak the same language, and I no longer struggled to tame her echolalic alien tongue.

The first time I left her completely on her own, she was asleep in her bedroom. It was just for a few minutes while I got groceries, and I only had to check the app to see if Harper was sleeping soundly. Her heart rate and breathing just needed to be in the green. Sometimes, I’d turn her off and leave her wherever she felt comfortable—the living room couch or the small space in between two parallel bookshelves. Absolution’s smiling cartoon infant cooed and that’s all I needed to put my phone away and enjoy myself for a few hours on the days when Harper was in my care, when all that stood between her and the world was a locked door. All that drove me was need.

August 14th, 2017 11:59 a.m.

When I tell you to put your shoes in the coat closet, for some reason you place them, along with your socks, in one of my comic book boxes stacked on the floor. You’ll lift a lid and set them right on top of books or in the empty spaces between them — never on the floor, against the wall, where I’ve asked for them to go. But you’re so satisfied. You have this proud smile on your face. My heart wells up and I clap for you. You’ve followed a two-step prompt. I think you compartmentalize my command in the same way you stow those shoes. Your brain is turning things in a way I just don’t understand. Is this how you process things? Do you put them in boxes? How much of your planet am I unable to explore?

In these moments when I’m alone, the thought of not being with you is too much. You’ve got me putting my shoes in there, too.

I wasn’t sleepy. I was tired. I was tired and I’d lost my senses. Earlier that day, my girlfriend and I took Harper to the zoo. Afterwards, we met up with some friends at a blues festival downtown. The three of us stunk of sweat and animals. Our knees were weary from all of the walking. But Harper was in love with the live music, so we stuck it out for her. She was in her element, swooping and careening in an open street to rhythm guitar, translating her inner joy into bodily language that made her one with the crowd. Next to the stage, Harper assimilated with everyone else. It was strange to see her that way. People embraced her in a place that felt, oddly, safe. My girlfriend looked at me and smiled.

“Concert people are the best,” she said. I dropped my guard. I held Harper’s hands and we spun in a circle. Stage lights morphed into long streaks. Harper was the only thing in focus. We spun our way into a silent disco tent and danced in slow motion against strobe lights, neon-flashing fireworks, pink glow sticks like heart lights and for a moment, I forgot about her therapy schedule. I didn’t worry about the sleep routine or when I would need to drop Harper off with her mom. Assured in parallax, I could see.

It was late when we got home. We were up past our bedtime, and I knew none of us would sleep if I didn’t do something soon. I tried to snare Harper in a blanket. As she fought, static crackled, small electrical storms popping in the dark like there were a thousand misfiring stars.

The sun had been up for an hour and Harper hadn’t slept. I held her close to me, her legs wrapped around my waist, my arms locked around her torso in a tight embrace. She wrenched an arm free in frustration and dug at my temple hard enough to get to my brain. I shouted at her that it wasn’t okay. She shouldn’t hit. I was reminded of the first time I’d seen her on an ultrasound — her brain, her spine — all within view, forming before me, something unrecognizable and familiar in the same breath. It knocked the wind from me. It was uncanny. For years, I’d struggled to put that feeling into words.

Getting Harper to sleep had once been about hitting the right rhythms — Clonidine, melatonin, deep massage, and patience. Don’t put her to bed too early. Don’t hesitate a minute too late. No electronics after eight, at least one story before bed. I’d done this dance a million times, but I didn’t always get it right, and the tempo would change without warning. There were evenings I got angry with her but kept it to myself. On this morning, I got angry with myself because the hole I punched in my kitchen wall wasn’t her fault. I blamed the changeling, this bewitched, half-conscious version of myself. I wasn’t just asleep or awake.

I reached a point of no return and threw open her bedroom door. Harper hung over my shoulder, writhing and straining her throat. I don’t know how one kid could hold so many tears. I wasn’t careful about setting her in bed. When I pulled my phone from my pocket, I didn’t think about the doctor’s sound advice — to take it slow, ease her into sleep. I didn’t think about it. A large part of me is afraid I didn’t care.

“Shut up!” I screamed, “shut up and go to bed!” Harper really erupted. She bounced on the bed. She practically catapulted herself through the ceiling. She reached for me, and I shut her off in one quick stroke. I didn’t know what would happen. She went limp, hit with sudden gravity. When we play, we call it “wet noodle.” A ragdoll on the bed, Harper’s limbs briefly twitched before becoming still.

The sudden silence was deafening.

August 13th, 2017 7:25 a.m.

I’ll always need sleep. And I’ll find some almost every night of my life until I can’t wake anymore. It’s so easy to forget that, how I’ll always sleep despite the sun. Day and night are arbitrary.

It’s easy to take for granted early mornings with you, Harper. Maybe you just want me to see the sunrise.

I’m grateful to sit on our patio with you and watch fog lift off of our pond. I love the sound and smell of watermelon pulp you suck from your grubby fist. I feel lucky to exist in these moments. I realize that, without you, I’d be well rested and inexperienced. I wouldn’t know how you like your melon cut. I wouldn’t hear you converse with geese.

I feel you beating forever outside my chest. My heart is saturated. It seeps with love for you, little girl, and each of your despairs is a pinpoint poised to make it burst.

I didn’t bother to set an alarm. Our early Saturday morning became Saturday afternoon, and my first thought upon getting up was how many comic books I could read before waking Harper. Perhaps I could fit in a little bit of writing or grade some student essays I’d held onto for too long. I puttered with the coffee machine, watched granola fall slowly into a bowl of vanilla yogurt. Medication, I rationalized, is a tricky thing, but it’s meant to help people. Perhaps there was a silver lining to Harper’s brain being shocked into submission. I’d been gifted some time to sleep in and gather my thoughts. Maybe I could watch some TV.

Parenting Harper had given me a disdain for the small rules that maintain social order, so I didn’t bother to open the blinds, gather the mail, or brush my teeth. Even though I felt bad, shutting her off like that surely wasn’t the end of the world. Neither was the time I wasted scrolling through Facebook and watching videos on Youtube. Absolution had sent me notifications just an hour before. “Time to wake your little one up!” it said. “Tap the screen now.”

I locked my phone and stared at the ceiling for a long time. That post-divorce apartment had a ceiling with a voluptuous curve like an open book, an ocean wave or bird’s silhouette. I read the ceiling and let my eyes get heavy. I ignored the anxiety of wasting daylight that set in with each buzzing of my phone.

Time to wake up. Time to wake up. I thought of those late nights when I’d driven Harper. Car rides used to calm her down. They were cold evenings when I paced outside myself, when my nose stung and eyes watered as I carried Harper to the car wrapped in a blanket. I kept the same Ben Folds CD in the dash. We navigated winding country roads. High beams up, the volume low, the piano was soft, and one of Harper’s favorite songs admitted, “You’re so much like me. I’m sorry.” With the dashboard bathing her reflection in cool blue, Harper’s eyes never met mine. I always noticed how she stared out of her window at the blackness and an occasional glimpse of passing trees. What was she looking for? There were a few times I almost fell asleep, too. But I always jerked awake with awareness that I held our lives in my hands. I rubbed my neck and tried to keep an eye out for deer.

I dreamed of the sound her therapy brush makes when I massage her arms and legs. It’s soothing — like brushing a horse or rocking ocean waves.

Pipes in the wall woke me up. The sun had started to set. I unlocked my phone and checked a litany of alerts.

Time to wake up. Tap to wake your little one up. Wake up. Wake up.

I hit the right button. But I was met with an error. “Oops,” it said. “Something went wrong.” But it couldn’t say why. Not really. I tried it again. “Oops.” Again. “Oops.” I rebooted by phone. The blackness of the screen lasted for what felt like a lifetime. I saw my dark reflection. The null ate at me. Once the app re-launched, I tried again. Nothing.

Harper was still in the same position on her bed. Her legs were tucked underneath her. Her mouth was ajar. She had a blanket snared around her foot and her hair spilled from her head, draped down her pillow. A fear gripped me that I didn’t know what I would say, how I would frame it. How could I explain I’d been away too long? That my phone wouldn’t do what it was supposed to do? That I didn’t understand the science of decreased synaptic plasticity, or I hadn’t learned anything from my own salient memories?

I shook her. Checked her breathing. Tried the app again. What day was it? Was the doctor in? I tapped and tapped and shook and cried. How often did I throw tantrums?

I ran to the living room and checked our WiFi. I frantically looked for the paperwork from our pediatrician. I realized Harper is not just an extension of me. My time with her has to be shared with her mom because she’s a piece of us both. She may be my daughter, but she’s hers, too. She’s her own person and I am not Harper’s only home.

I heard a groggy “daddy” come from her bedroom. It was just quiet enough that I thought I’d imagined it.

March 29th, 2017 2:59 p.m.

Sometimes, it’s hard to play with you. You’ll occasionally flick ants into plastic pants or pluck cherries from a small cardboard tree. There are days you want to ride my shoulders. I’ll gallop up and down the hallway, neighing like an awkward horse. But you only allow me in when you want to. I can’t often meet you where you stand. You seem light years away when I wish to reach you, even if it’s just for a visit.

The miracle of playing catch with you for the first time, bouncing that giant exercise ball back and forth, immediately carved a crater in me. I’m still astonished, and grateful, for that reciprocal exchange. You got “too happy” and scratched me when the game was over. We’d fallen to the floor and I tickled your belly. I wasn’t mad about the blood you drew. I watched the wounds scab and wither for weeks after. They reminded me you’re here, with me, on earth. Together, we jumped and our house became unsettled.

You didn’t sleep last night. Today, I’ve been living in a livid state, suspended in half-sleep. I’ve daydreamed about weird landscapes and caught myself being rude to a coworker. Tonight, I plan to share grocery store ice cream with you. I know you’ll spit the chocolate chips like cherry pits because you don’t like their texture. And I’ll be prepared to clean them up. But it shouldn’t make me mad. I’ve often blamed you for my own capacity to be both the best and worst versions of myself. If there exists in me an ability to judge unfairly, to set you up for failure, then I worry about how all these aliens around us — strange, faceless people — will treat you.

Yesterday afternoon, we played in the labyrinth at Hawthorne Park. It was cold. I forgot your hat, but you didn’t seem to mind. You were at home on the open asphalt among errant piles of brown leaves. As I walked the painted maze, a man and his son came into our circle. They cut across the lines and set themselves up uncomfortably close to us. I don’t think you noticed. You instead threw your kickball to the ground and watched it bounce as high as your strength could manage. You seemed to be enamored in the ball’s shape, in its endless distance to the sun. The father and son began to spar. It was a ritualistic lesson in combat. I was mad at their lack of awareness, at colonizing our play, but as I pulled you away from the maze, I realized that we’ve been fighting, too. Maybe I’m not teaching you what’s important. Maybe our battle is just too different.

You don’t often sleep. But when you do, I’m left wondering if you dream. Maybe, when we’re both asleep, we dream at the same time, even when you’re with your mom and seem a world away. My favorite dreams are the ones in which we’re together and our bad days are behind us. Often, you sing or tell me stories in a voice I imagine sounds like your own. You extend your hand through the space between us and I know you’re okay. •

All images by Isabella Akhtarshenas.