The veneration of holy relics has long been an easy target for Protestants, atheists, and just about anyone who didn’t fall into the hardcore Catholic fold. Even the Church itself has downplayed the role of relics since the Vatican II reforms in the early 1960s. But odd as it may be, relics are making a comeback. Don’t believe me? You should have witnessed the masses in England who turned out two months ago to pray in front of the bones of St. Therese of Lisieux that were touring the country, or the crowds who gathered to see the bones of Mary Magdalene last month, taken on a U.S. tour by a French monk.

Today we may have health care, the lottery, and recreational drugs to help us get by. But for the typical Christian in Medieval Europe, the sacred shards of bone, strands of hair, and flakes of skin were like calling Dial-a-Devotion straight to the promised land, tugging at a saint’s leg in the hope the divine individual would talk up your request with the Big Man. But in some rare cases, that piece of sanctified stiff might have belonged to the CEO of the celestial sphere himself — Jesus. Or perhaps his mother. Never mind that Jesus and the Virgin Mary ascended into heaven bodily; that didn’t stop a few relics — both physical possessions and improbable body parts — from materializing on the spiritual landscape of Europe.

You’ve heard of the Shroud of Turin and the many pieces of the True Cross, but unbeknownst to a lot of us, there were — and in many cases, still are — bits and pieces of the Holy Family on display and ready for your veneration. Here are my 10 favorites.

10. The Holy Swaddling Clothes

|

| Shrine of the Virgin Mary, Aachen Cathedral. |

It would seem relics of Jesus’ infancy would be a rare commodity. The heads of the Three Wise Men (or Kings, as they’re sometimes referred to) — while not being a Jesus relic but associated with his birth — are housed in the grand gothic cathedral of Cologne, Germany (even though they’re only mentioned in Matthew and there’s no number of these men given). In the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, one can eye Christ’s crib, which today has been whittled down a few pieces of wood. But one of the most remarkable Baby Jesus relics is his swaddling clothing. A Holy Shroud of sorts for babies. Relics scholar Joe Nickell recounts some of the miraculous experiences associated with the magical Holy Onesie in his book Relics of the Christ, noting that the clothes have reportedly exorcised demons from a young man and also burst into flames in order to scare away a dragon. Today, the swaddling clothes can be found in Aachen, Germany, the town that was the HQ for the great Gallic king Charlemagne. A tale attached to the clothing says that he attained it from the Holy Land. Just leave your dragon at home.

9. The Holy Girdle

Alongside Baby Jesus’ swaddling clothes (and the Virgin Mary’s shroud), Jesus’s loincloth is still prayed over in the Cathedral of Aachen. But the Tuscan town of Prato has its own sartorial prize: the Holy Girdle, housed in the Pisano-designed Cathedral and in a chapel partially designed by Renaissance master Lorenzo Ghiberti. The Holy Girdle is said to have made its way to Prato thanks to one of the many booty-loaded Crusaders who made their way back to Europe from the Holy Land. The green girdle is displayed five times a year on major Catholic holidays.

8. The Holy Nails

|

| A nail with reliquary in Trier, Germany. |

Early Christian writers claimed that Jesus was crucified with four nails. But like the pieces of the True Cross, the Holy Nails have been possessed with the gift of multiplying. Nearly 30 towns in medieval Europe could claim one. There was, of course, an explanation for this, as it was unclear if the provenance of said nail was one of the traditional four pounded into Jesus or if it was one of the (presumably) many that held together the True Cross. Or, as some historians have suggested, just a nail that simply touched one of the real nails. Whatever the case, there were enough of these going around that they seemed rather expendable: Saint Helena was said to have tossed a nail into the sea near Venice to calm a storm. Her son, Constantine, the first Christian Roman emperor, supposedly affixed one to his war helmet. Perhaps in a proto-MacGyver moment, he also refashioned one as a bit for his horse’s bridle. Today relic gawkers can spot a nail at relics-rich Santa Croce in Gerusalemme on the outskirts of Rome.

7. The Holy House

|

| The Holy House, Vatican Museum. |

One of the most magical relics is the House of Loretto, said to be the abode of the Virgin Mary. According to legend, angels first carried it from the Holy Land to the Dalmatian Coast on May 10, 1291. But, as the historians G. W. Foote and J. M. Wheeler wrote in 1887, “[I]t was too precious a memorial of the true faith to be left there; and after a rest of three years, during which its angelic conveyancers were perhaps recovering from the fatigue of their first journey, it suddenly and miraculously appeared in the Papal state of Loreto.” The Santa Casa, located 15 miles from Ancona, Italy, has become a regular pilgrimage site. You can also find a “replica” of the Holy House in Prague.

6. The Holy Robe

|

| Holy Robe, Trier Cathedral. |

John writes in the Bible that after Christ was crucified, soldiers divided up his clothes. The real prize was his seamless robe and after an argument over it, the soldiers settled by playing dice. The next time the seamless robe appears is in a tale that Charlemagne gave it to the French town of Argenteuil. The robe, however, was apparently stolen by left-wing terrorists in 1983. Thankfully, the German town of Trier has a Holy Seamless Robe as well, said to come from Saint Helena’s fourth-century relic shopping spree in the Holy Land (she also brought back Holy Nails, hunks of the True Cross, and the finger of doubting Saint Thomas, among many other relics). The Cathedral in Trier — the oldest in Germany — trots out the robe on rare occasions. In 1933, the robe drew two million pilgrims. It has been shown in public two other times since: in 1959 and 1996.

5. The Holy Blood

|

| Basilica of the Holy Blood, Bruges, Belgium. |

Medieval pilgrims had an insatiable thirst for the Holy Blood, which made crowds gasp and swoon and empty their pockets into church coffers. The blood was assumed to have been spilled during Christ’s crucifixion but strength in the belief of such provenance was best left to one’s own faith. Rome, of course, was a virtual Holy Blood bank (in Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, in San Giovanni Laterano, and Santa Maria Maggiore). So was — surprise, surprise — France (Fecamp, Soissons). Since the 12th century, though, the most notable claimant has been the Belgian town of Bruges. Because the blood would liquefy for the faithful every Friday, Pope Clement V gave his official stamp of approval on the Bruges blood in 1310 with an indulgence to those who came to venerate it. But after a blasphemy occurred later that year the blood refused to perform its weekly stunt, only liquefying once more in 1388. To this day, though, every May 21 the blood is the star of a lengthy procession through the streets of this handsome, gothic-clad city.

4. The Holy Umbilical Cord

It was written somewhere that the Virgin kept and coveted her son’s umbilical cord. She possessed it most of her life before handing it off to Saint John who, in turn, passed it along (as the story goes) to the Bishop of Ephesus. But how versions of the Holy Navel ended up in the French towns of Lucques and Châlons-sur-Marne is a mystery, especially considering Rome had one, too. The Eternal City’s blessed belly button was kept in the Sancta Sanctorum (the Holy of Holies) along with the heads of Sts. Peter and Paul, a chunk of wood from the Last Supper (which can still be seen tacked to the wall), and, until 1527, the Holy Foreskin (more on that later). Today the Sacred Umblicus is nowhere to be seen — not that it might stop someone from discovering one at some point in the future. Stay tuned.

3. The Holy Teardrop

Jesus ate, drank, clipped his toenails, relieved himself, and, as bumper stickers often proclaim, saved. He also cried. One of his most industrious followers who must have risked grave danger in leaping, vial in hand, to catch one of Jesus’ tears before it hit the ground. In fact, there were enough tears on display in European churches in the Middle Ages that Christ’s sadder days must have caused a scramble among his disciples. French towns Marseilles, Picardy, Orlean, and Auvergne, among others, all displayed depositories of sacred saline that were venerated. Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume and Vendôme went a step further by giving provenance to their holy teardrops, claiming they were shed by Christ on the tomb of Lazarus. All the holy teardrops have since dried up and vanished, many the victims of French Revolution fervor, but Vendôme pastry shops still sell chocolate teardrop-shaped cookies in homage to the town’s now long evaporated tear.

2. Holy Breast Milk

|

| “Madonna with Four Saints,” Rogier van der Weyden. |

Throughout the centuries, the cult of the Virgin Mary has rivaled that of her son’s. And so have her relics. Like Jesus, Mary ascended bodily into heaven. But that hasn’t stopped creative devotees from unearthing bodily relics of the Virgin. The most outrageous is her breast milk, which French scholar Nicole Hermann-Mascard traced to 69 sanctuaries, 46 of which were in France. The part of a pilgrimage route that traveled through the English village of Walsingham was known as the Milky Way because of its fame for possessing a drop of the beloved latte. “Had the Virgin been a cow,” wrote the 16th-century Protestant reformer John Calvin, “she scarcely could not have produced such a quantity.” One lucky relic collector boasted the two-for-one relic: the Holy Bib, which contained stains of Mary’s breast milk. Calvin later added: “I would fain to know how that milk . . . was collected …. We do not read of any person who had the curiosity to undertake the task.”

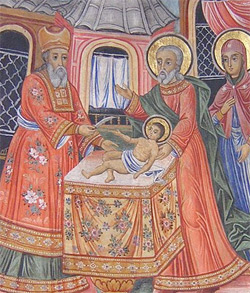

1. The Holy Foreskin

|

| Circumcision of Christ, Preobrazhenski Monastery, Bulgaria. |

As Catholic scholar James Bentley wrote of Holy Family curios: “None, however, ranks in absurdity with the cult of…the Holy Foreskin.” There’s only one reference to Jesus’ circumcision in the Bible — in Luke 2:21: “And when eight days had passed, before His circumcision, His name was then called Jesus, the name given by the angel before he was conceived in the womb.” But as Jean Calvin quipped: “They couldn’t let Christ go without keeping a little piece of him.” The foreskin of Jesus has loomed on the periphery of many historical epics and movements, from the Carolingian legend to the Papal Schism to the Reformation to 19th-century Romanticism. Though there were at least a dozen claimants to the Holy Foreskin (as you’d expect by now, most were in France), the papal-approved version was stolen during the 1527 Sack of Rome and ended up in the hill town of Calcata, 30 miles north of the Eternal City. By the end of the 19th century, the relic fell out of favor with the church, highlighted by a papal decree in 1900 threatening excommunication to anyone who writes or speaks about the miraculous membrane. Still, the relic remained in Calcata until 1983 when it was stolen under mysterious circumstances, leaving the villagers of Calcata with wild theories on its disappearance: that neo-Nazis, Satanists, and/or even the Vatican itself was to blame. • 7 December 2009

Sources/Further Reading: Bentley, James, Restless Bones: the Story of Relics (London: Constable and Company Limited, 1985); Nickell, Joe, Relics of the Christ (Lexington, Kentucky: University of Kentucky Press, 2007); Foot, G. W. and Wheeler, J. M., Crimes of Christianity (London: Progressive Publishing Company, 1887); Boussel, Patrice, Des réliques et de leur bon usage (Paris: Balland, 1971).