The first sentence of A Christmas Carol is “Marley was dead: to begin with.” It’s a terrible way to start a story about Christmas. But A Christmas Carol isn’t great because it’s a great story. In fact, A Christmas Carol is a flimsy story. The characters are mostly clichés. Scrooge is a parody of miserly behavior. He is not only against Christmas, he is against love. He is also against charity, kindness, and even heat, preferring to keep his coal locked up rather than warm the office with it. Scrooge lives in darkness and gloom. “The fog and frost so hung about the black old gateway of the house, that it seemed as if the Genius of the Weather sat in mournful meditation on the threshold.”

In contrast, Tiny Tim — the blessed little cripple and son of Scrooge’s employee — seems to bear no resentment to the world at all. His love for everyone knows no bounds, despite the fact that Scrooge has done everything in his power to keep the Cratchit family in misery. God bless us, every one, and so forth.

Then Scrooge has some bad gravy, a nightmare about three ghosts, and he spends Christmas Day in a hysterical fit sending turkeys all about the city and giving everyone raises. He’s so happy not to be dead (as the third ghost suggested he soon would be) that he has a chuckling fit and bursts into tears, perhaps having gone insane. An unbelievable asshole but a day ago, Scrooge is now the picture of human kindness. I, for one, don’t buy it. Despite Dickens’ assurance to the contrary, I think Scrooge came to his senses a few days later and started busting balls again. Tiny Tim died. No way he could have survived.

This explains why the movie versions of A Christmas Carol are so roundly disappointing. When you strip it down to plot, there simply isn’t much there. But that is Dickens for you. His greatness is of the slippery sort. Filmmakers want to capture some measure of his magic, so they take the stories and the characters, they tell the tale, but all of a sudden they’ve lost it. Dickens is Dickens because of his voice, because of the way he flips sentences around and goofs his way through plot.

A Christmas Carol is great because of paragraphs like the following, where Dickens is explaining to us that Scrooge’s partner Marley is dead (an important plot point since it is Marley’s ghost who will soon visit Scrooge and warn him about the three ghosts of Christmases past, present, and future that will visit him in the night):

The mention of Marley’s funeral brings me back to the point I started from. There is no doubt that Marley was dead. This must be distinctly understood, or nothing wonderful can come of the story I am going to relate. If we were not perfectly convinced that Hamlet’s Father died before the play began, there would be nothing more remarkable in his taking a stroll at night, in an easterly wind, upon his own ramparts, than there would be in any other middle-aged gentleman rashly turning out after dark in a breezy spot — say Saint Paul’s Churchyard for instance — literally to astonish his son’s weak mind.

I particularly like the bit of honesty about Hamlet, something we’ve all suspected but rarely voiced. Hamlet is soft in the skull, perhaps a little retarded. Dickens does all of this to re-establish an already perfectly clear point of plot, which is that Marley is dead. The first sentence of the story is, after all, “Marley was dead: to begin with.” Dickens does this because he knows the plot is thin, he wants to shift your attention to the way it’s told, to the way he writes.

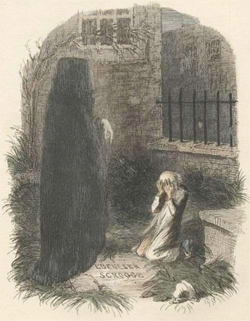

Later in the story, at the appearance of the first spirit, Dickens describes what happens as the ghost approaches Scrooge in his bed. “The curtains of his bed were drawn aside; and Scrooge, starting up into a half-recumbent attitude, found himself face to face with the unearthly visitor who drew them: as close to it as I am now to you, and I am standing in the spirit at your elbow.” The remarkable thing here is not so much that a ghost appeared to Scrooge but that Dickens himself is a ghost appearing to us. Dickens’ authorial voice does come directly into our heads at that moment. In this, the joy of writing becomes the very substance and content of the story. Almost no writer gets away with this kind of playfulness very often. Dickens gets away with it all the time. And A Christmas Carol is utterly charmless without that extra element, without Dickens constantly nipping at the heels of his own story. It makes me think that we ought to reconsider Dickens, to see him more in the light of a Lawrence Sterne than in the light of the straight shooters of 19th-century novel writing. • 8 December 2009