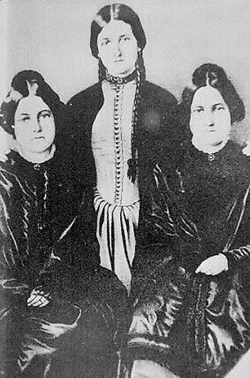

And just like that, America was haunted. When exactly the apparitions began appearing no one could say for sure. It was the middle of the 19th century — maybe 1848? This was the year that the young Fox sisters, Maggie and Kate, began communicating with the ghost of a murdered man who had been buried in the cellar of their new house in Hydesville, New York. The girls listened to his frantic rappings beneath the floorboards and created a Morse code of sorts to parse the meaning. Their mother called in the neighbors to witness her daughters’ supernatural powers and the neighbors’ excited whispers stretched to surrounding towns. They particularly excited Amy and Isaac Post, a progressive Quaker couple who were friends of the Fox family. The Posts relocated Kate and Maggie to their home in Rochester and soon the girls were performing séances for the Posts’ reformist friends. Strangely, the rappings followed them all the way there. The Rochester rappings became known all over the country, talked about by William Cullen Bryant and P.T. Barnum and Mary Todd Lincoln. The Fox sisters — now famous mediums — had started a movement. They were just 12 and 15 years old.

Or, the hauntings could have started the year that Mary Andrews began conducting séances from her house on Oak Hill Road in the western New York village of Moravia. Her nightly spirit conjurings drew thousands to Moravia — the hotels there were always full, despite being haunted too. In 1872 Mary Todd Lincoln came to the house on Oak Hill Road, searching for her own ghosts. These famous events turned Moravia and the nearby city of Auburn — a new city built on the wealth of the Erie Canal — into the Mecca of the Spiritualist movement. From there, the ghosts would spread. They would appear in familiar haunts all across the country — overlarge hotels, moldering basements, the salons of the rich.

Mediums will tell you that the ghosts are always there, that we the living share this earth with the dead. Sometimes the dead can be called from the underworld and invited to join us for tea. But some restless souls get stuck between heaven and earth, they don’t know how to go home. Their despair lingers in dark closets and they appear to the living when their restlessness is strong. This is what ‘apparition’ means. It is an appearance, a revelation of something already there. And every so often, a living person who is extra perceptive — often a child and usually female — becomes a breathing channel for spirits, a voice for the voiceless, a bridge between life and mystery, a bridge between now and then.

For some reason, the spirits started appearing in the middle of the 19th century and mostly around Seneca Lake in western New York. For thousands of years after Ice Age glaciers melted into finger-shaped lakes, this small part of the world was mostly filled with animals and people living out in the greenery. In the 18th century genocide arrived in the Finger Lakes, in the guise of an American General named Sullivan whose job it was to destroy all the villages of the Native Americans living there. American settlers showed up soon after to build humble cabins and live modestly upon the graves of the Iroquois. They lived there invisibly for 20-odd years, just hours from New York City, until one day in 1825, they looked into their fields and realized an enormous canal had been carved into the hills. Not long after its completion, the builders of the canal decided that it wasn’t enormous enough. So, in the 1840s the Erie Canal was carved deeper and wider and busier and louder. Steamships and industry roared over farms, turning villages into towns and cabins into mansions.

The Erie Canal became an information superhighway that carried the ideas of progress all around New York State. As industrialists sipped whiskey on their brand-new verandas, runaway slaves traversed an underground city below them. Frederick Douglass sat in the back of the Wesleyan Chapel in Seneca Falls at the First Women’s Rights Convention, listening to Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott and diligently taking notes. A few miles down in Auburn, the home of Harriet Tubman became a haven for fugitive family and friends escaping slavery. Hicksite Quakers in Rochester called for a boycott of slave-made products and preached radical nonresistance. A bit further east, the Oneidists created a Communalist Utopia. They promoted free love and equality and believed they were living in heaven on earth. Utopianism and religious revivals and Pentecostals preaching the Second Great Awakening inflamed the whole region. William Miller predicted Jesus would surface in upstate New York around 1843, and when Jesus failed to show, his disappointed Millerite congregation became the Seventh Day Adventists instead. Up in Palmyra, a 14-year-old farm boy named Joseph Smith was utterly overwhelmed by all the Protestant sects blazing through his community — he couldn’t make up his mind which to choose. Then, he had a vision for an entirely new religion that was shown to him by an angel. Thus was Mormonism born. In 1876, Charles Grandison Finney called this region of Western New York “Burnt-over” because by then there was no one left to convert. The region drew reformers from Boston and Washington, D.C. and Philadelphia — it was the place to be. As fast as you can imagine, upstate New York was not just part of the story of American progress. It was the story of American progress.

This is all to say that antebellum northeastern America was spiritually itchy. Prevailing theologies were insufficient to those who were looking for relief. Many established churches had little to say when it came to women’s rights and ending slavery. And then there were the ghosts. The more people talked about them the more ghosts appeared, and word of the hauntings ran the length of the Canal. Hardboiled journalists and famous scientists poured into the region by the boatload. They came ready to debunk and denounce. Frederick Douglass — a good friend of the abolitionist Posts — visited Rochester in 1850. He listened to the rappings, he later wrote in the North Star, and was respectfully unconvinced that their source was “unearthly.” But more often than not, people came as skeptics and left as true believers. The legendary newspaper editor Horace Greeley was fascinated by Spiritualism — for a time the Fox sisters lived in his home. The spirits and their mediums were increasingly invited to dinner parties thrown by progressive elites. In these circles, séances were no mere party game, “midnight fumblings over mahogany” as Emerson sneered. Communing with the dead was part of the mystical revolution.

The tenets of Spiritualism were an assortment of ideas taken from the somewhat messier domains of the Enlightenment. These ideas were merged with the reformist ideas of the day. Spiritualists talked about Emmanuel Swedenborg, about the spongy boundaries between the material and cosmic worlds, about the individual’s inner core of divinity. They talked of the philosopher Charles Fourier, who wrote of a new world order based upon a universal harmony. They wrote of the experiments of the physician and arts patron Franz Anton Mesmer, who believed in an interconnectedness between all the heavenly bodies and natural life forms, that energy moved from the planets to the human body and could be passed from one body to another through this universal force. To say you were a Fourierist communitarian and a feminist and maybe a Transcendentalist and an abolitionist and a Spiritualist was stylish and understood. It all boiled down to one basic understanding: That Americans were little parts of a greater social-spiritual whole, that all people were a unified species to be organized in a perfect fellowship, as Henry James would say.

This points to an important fact of Spiritualism. It’s not that Spiritualists were the only Americans who believed in ghosts. Americans have historically been, more often than not, believers. It’s not that people in the South, or African Americans, or Native Americans were less inclined to the supernatural. There was a reason why the ghosts all seemed to be gathered in the North. Spiritualism was transcendence for white antebellum intellectuals.

When we talk about a place being haunted — even if we do not believe in spirits and we are speaking only in metaphors — we are talking about the present being disturbed by the past. The “spirit” of the past comes knocking on our door and reminds us that we are not alone, lone actors in the land of now, unwatched by the dead actors of history. America in the mid-19th century was everything she set out to be — independent and wealthy, a country at peace, a civilized land whose borders were still mythic and wild. The heroic story of America had been written — and yet her citizens were panicked. Somehow the story couldn’t end just there, it didn’t feel quite right.

Spiritualists fit weirdly in the story of America, less because of what Spiritualists believed than who the Spiritualists were: physicians, scientists, writers, politicians, industrialists — white, prominent, educated, wealthy, Protestant. Though men were its primary defenders, women dominated Spiritualism — mediums were mostly female. A medium’s power was more than political; the ghosts made her practically divine. (Divine and also wealthy. Mary Andrews earned $1,000 a week in her séance heyday; her husband was happy to encourage her.) Spiritualism spoke to America’s so-called enlightened, in other words, those in charge of America’s public conscience. These leaders of mid-19th century America had become uncomfortable. They were as restless as the ghosts. They knew that America was getting ready to explode, that she must change ruthlessly and hard. They saw ghosts in their palaces and government halls, in their churches and in their homes. The ghosts were catching up with them, they were America’s conscience erupting. When Mary Todd Lincoln moved into the White House she said she saw ghosts everywhere. She set up a room in the Presidential home for séances just a year before the Civil War’s start and the transformation of the country was sealed.

By the end of the Civil War in 1865, half of Americans were ghosts, and Spiritualism went mainstream. Then, just like that, the ghosts were gone. Some of them showed up in England, a few decades later, at the end of the first World War. But in America they silently receded back under the floorboards. In the 1880s, the Fox sisters told the papers that they made the whole thing up. Only nobody would believe them.

Western New York is quiet now, its restlessness long past. In the Cayuga-Owasco Lakes Historical Society, Moravia’s resident historian and one of its last remaining Spiritualists, sits in her office cheerfully drawing pies on the backs of fundraiser mailings. Her museum is a single darkish room dedicated to Moravia’s most prominent citizen, Millard Fillmore, whose life is showcased with dusty family memorabilia and miscellaneous local items thrown in for filler. In a corner of the room, blocked off by dividers next to the kitchen, is a little exhibit of Xeroxed pictures and newspaper articles providing a short history of Spiritualism. It is a presentation of a strange and forgotten movement, and of a country’s existential crisis. The ghosts are sleeping now, the exhibit says, but they could stir at any moment. • 25 July 2013