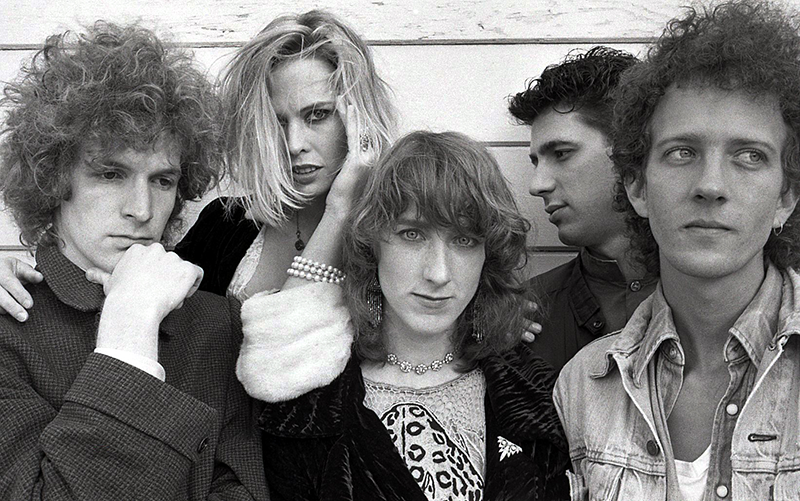

When Donnette Thayer thinks about the definitive moment of playing in Game Theory — the much-beloved, if woefully underappreciated, San Francisco pop band in which she held down guitar and vocal duties from 1986 to 1988 — she thinks about the wine glasses.

Thayer, the late Game Theory frontman Scott Miller, and producer Mitch Easter were listening to the finished tracks on the band’s final album, Two Steps from the Middle Ages, when their review of the L.P. opening, “Room for One More,” was interrupted by a studio employee putting away stemmed wine glasses.

As the glasses clinked together, “they made the most beautiful, bell-like sound that fell into the track like it belonged there,” Thayer recalled in a written interview.

She told Easter, best known for producing R.E.M.’s debut E.P., Chronic Town, and its first two albums, Murmur and Reckoning, that they had to find a way to add the glasses to the track.

So they did. They nailed it, and the sound of clinking glasses ended up on the final version of song.

“Years later, that moment stands out for me because it symbolizes so much of what I loved about Scott’s writing and what we did as members of Game Theory,” Thayer wrote. “Our glasses may seem empty by traditional standards — but this was unimportant to us . . . We had different objectives.”

In the 27 years since Miller called time on the band, that legacy has only grown and fan loyalty has only intensified.

And this summer, Two Steps from the Middle Ages gets the full reissue treatment from Los Angeles-based Omnivore Recordings.

It includes all 13 of the L.P.’s Easter-produced tracks, liner notes from Easter and Posies co-leader Ken Stringfellow, and 11 bonus recordings that include live renditions and Miller’s original demos.

Unfortunately, Miller isn’t around to appreciate these re-releases. He committed suicide in 2013 at age 53. The band’s drummer, Gil Ray, has also since passed away, leaving a decidedly bittersweet taste to the proceedings.

If you listened to college radio in the 1980s (or were, like me, a high school kid who listened to college radio under your pillow and hung onto every note as if it were a lifeline), preferred your rock brainy, and were the sort who used the adjective “angular” to describe the kind of guitar-pop you enjoyed, then Game Theory was your ideal band.

There were so many of those bands in those days. Skinny kids with big hair who channeled the best of post-punk and the ideals of the 1960s. R.E.M., of course, were at the leading edge. But so many bands — who sprung out of Athens, Georgia, or North Carolina, or somewhere in northern California or Los Angeles — some better remembered than others.

Miller and Game Theory were among them, hitting all the right notes, combining a melodic sweetness with coruscating guitars.

Game Theory’s debut Blaze of Glory wears its 1960s pop allegiances on its sleeve. But it also forges its own distinctively experimentalist path.

The opening, “Something to Show,” for instance, is prefaced by an explosion of bells, while “White Blues” is driven by a pulsing keyboard line.

The band hit its apotheosis on Lolita Nation, a double album that went from a merely sprawling 27 tracks on its initial release in 1987 to a truly epic 48 tracks, courtesy of Omnivore’s February 2016 re-release.

The record “checks all of the boxes of the sprawling, ambitious double album,” The Paris Review’s Adam Sobsey wrote in a lengthy retrospective last year.

The album’s “knotty but grabby songs are interspersed with bursts on experimental noise [and] rash new musical ideas,” along with “references to The Beach Boys, Led Zeppelin and Kubrick,” Sobsey wrote.

It’s a challenging listen. And that’s probably the way Miller preferred it.

Tim Lee, the co-frontman of the Mississippi-based power-pop band The Windbreakers, who recorded with Easter during those days, called Miller “one of a kind.”

“I only got to hang out with him in that ‘Hey, we’re on the road together’ kind of way, but we got along well,” Lee wrote in an email interview. “The Windbreakers and Game Theory played several shows together in the mid-80s, mostly in the Midwest. He was completely sweet in the way you’d imagine, so easy to be around.”

When Lee thinks of that signature Miller moment, his memory turns to a “night we shared a bill in the basement of some college in Milwaukee.”

“I think we played first, but ended our set with a cover of Led Zeppelin’s ‘Tangerine,’” Lee wrote. “Prior to starting, I asked Scott if he was familiar with the song and wanted to join us. He said yeah and hopped up on stage with us. When it got to the solo, I nodded at Scott and he played a stellar version of [Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page’s] solo, note for note.”

“That just slayed,” Lee recalled.

After folding Game Theory, amid a break-up with Thayer, Miller went on to form another well-regarded band, The Loud Family.

The band’s debut, Plants and Birds and Rocks and Things, again produced by Easter, was favorably reviewed. The band even landed a Rolling Stone feature, putting them alongside such then-newbies as Liz Phair and Radiohead.

As The Paris Review’s Sobsey notes, Miller released two more Loud Family albums to diminishing artistic and commercial returns and went into a kind of semi-retirement.

He launched a blog, and his “Ask Scott” column became a must-read of the early internet. Those columns have since been collected into a book.

After Miller’s death, it emerged that he’d been planning a new Game Theory album with the working title, Supercalifragile.

Miller’s widow enlisted The Posies’ Stringfellow, along with some Game Theory bandmates, to finish the L.P., which is to be released this year, according to the band’s Wikipedia entry.

Some of Miller’s fans see similarities between Game Theory and the Alex Chilton-fronted power-pop band Big Star. Some among them hope that Miller’s image will undergo a similar rehabilitation and that he’ll soon occupy a similar place in rock history.

“I hope that, as time passes, and the [Omnivore] reissues get more attention, people will understand the intricate genius of Scott’s songwriting,” Peter Holsapple, of The dB’s, wrote in an email interview. “Those were my hopes in 1972 when I first heard Big Star, and they’ve managed to come true some 40 years later, so it’s always possible.”

The Windbreakers’ Lee feels much the same.

“Like few others — folks with names like [Chris] Stamey, Easter and Holsapple, for instance — Scott had a brainy approach to pop music that was initially appealing,” he wrote. “But what I feel aligned him more with Alex Chilton and Chris Bell of Big Star, perhaps a little more than his other contemporaries, was the way he wore his heart on his sleeve in such a visceral way. So many of his songs still make me wince at their honesty.”

Thayer, who once knew Miller so well, isn’t as sure that mention of Miller’s name will ever elicit the same reverential hush that the mention of Chilton’s elicits among some pop fans.

“Barring some sort of fictionalization of the band, and given the plethora of music now available to compete for ears, Scott’s following is likely to remain static at best,” she wrote. “I wish I could believe otherwise.”

But, maybe if you were a kid who listened to college radio in the 1980s with a transistor radio jammed under your pillow or headphones wrapped around your ears, finding in the dark some lifeline to people who felt a lot like you did or made you feel a whole lot less alone, maybe that doesn’t make a difference.

Maybe it’s enough that Miller’s music is still alive, feeling just as essential as it did three decades ago. And if it reaches even a few new listeners through these Omnivore reissues, that’ll feel like a kind of quiet victory. •

Feature image courtesy of angrylambie1 via Flickr (Creative Commons). Second image also courtesy of angrylambie1 via Flickr (Creative Commons). Third image courtesy of Lwarrenwiki via Wikimedia Commons. Other images created by Shannon Sands.