When people ask me “Who is one of the best cartoonists working today?”, I always answer “Eleanor Davis.”

OK, nobody ever asks me that question. But if they did, that would be my answer all the same. At the risk of sounding like some back-cover, hyperbole-ridden hack, the intelligence, emotion, and pure, awe-inducing skill she continually exhibits in her comics make her one of the most significant creators to come out of the indie comics scene in the past 15 years.

I first became aware of Davis’s work with the various mini-comics she self-published between roughly 2003 and 2009. Working with her frequent collaborator and spouse, Drew Weing, she released a number of short comics that experimented with format and presentation while adopting or riffing on a fable — or folktale — like structure.

Since then, she’s produced a number of excellent books in a variety of genres, from children’s books (The Secret Science Alliance, Stinky) to slice-of-life tales (Libby’s Dad), memoirs (the stellar You and a Bike and a Road, which made my best of 2017 list), erotica (Frontier #11) and more. Each successive volume exhibits the same high level of craft and care (she has also proved to be remarkably adept in a variety of different mediums — her style has altered considerably since her early years).

A lot of Davis’s comics deal with characters attempting to cope with depression, anxiety, or just the overpowering effort of trying to get by in this modern world. In one untitled short story (found in the collection How to Be Happy), a woman turns from fad to fad in an attempt to stave off despair, with no luck. But then a friend mentions how wonderful it is to be gluten-free and the cycle begins anew. In “No Tears, No Sorrow,” a group of people attends a self-help seminar in order to learn how to cry. They are successful, but leave the seminar unable to contain their grief, falling apart in their cars and the local supermarket.

This concept is, at first glance, patently absurd, but — and this is one of the great things about her work — Davis is able to use this seemingly ridiculous scenario to say something about sharp and profound about human nature. She segues from the humorous and silly to the upsetting and emotionally raw with considerable aplomb.

All of which brings me to her latest release, Why Art?. Slyly dubbed the “fourth edition” on the title page, the small, square book begins as if it’s going to be a treatise of sorts, or will at least attempt to answer the titular question (the tongue-in-cheek blurb on the back of the book promises to guide the reader “through a metaphysical journey where the mysterious and regenerative properties of art are put to the test”).

Right away, however, we can see this book will be anything but an academic discourse. For one thing, Davis’s narrator begins by separating art into some odd categories. Under color, for example, we are presented (in black and white no less) with “blue” and “orange” objects. One of the blue objects is a small pig. No mention is made of the rest of the spectrum.

From there, the narrator notes goes on to discuss “mask” artworks, “mirror” artworks, and the popular “concealment” art which hides unpleasant things from view (“Some of us have student loans to pay off” exclaims a defensive sculptor in the midst of creating such a work). The narrator also darkly reminds us that there is some art “meant to remind the audience of things we’d rather forget, things so awful they shouldn’t be true.” This type of art is represented as a simple black square the slowly grows to consume the page. “Many people try hard not to look at this type of artwork,” we are told.

Very soon, however, we turn our attention to a loose affiliation of nine artists, each one working in a different medium (Jose, we learn, works exclusively in “concrete and fondant”).

We spend the most amount of time with Dolores, a performance artist who soon grows unnerved and then removed from her art, mainly due to the overly strong response from her audience. She then goes through a series of fantastical and life-changing events, including surviving a shark attack and growing back an arm. All this inspires her to create a new, demanding work, which people like. But of course, they ultimately prefer what she did before.

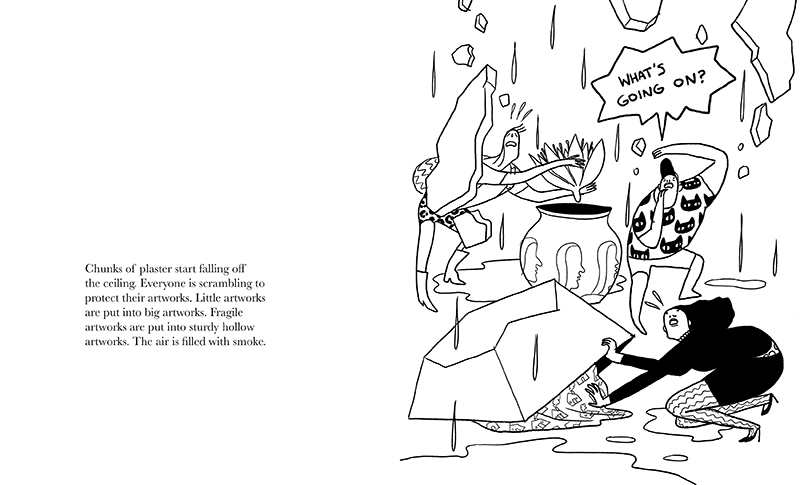

From there the group begins to work on a collaborative exhibit. But then catastrophe strikes. Rain pours in, destroying the art and their studio. A seemingly giant, godlike force obliterates the neighborhood. (It’s worth noting that it’s at this point that Davis’s third person, objective narrative voice suddenly switches to “we” and “our”.)

And, perhaps straight out of Jorge Luis Borges or Synecdoche, New York, the artists are forced to take literal refuge in art, first inside a papier-mâché head, then in a miniature shadow box. There they attempt to remake their world in miniature fashion. At first, they are content simply observing and delighting in the world they made. But Dolores has other ideas and pushes their doppelgangers to disaster in the hopes they can “show us how to save ourselves.”

Throughout her career, Eleanor Davis has proven herself to be extremely adept at exploring the ways in which empathy, sorrow, and art intersect and how often any one of these things can overwhelm us. That she does so not only with considerable insight but also with a good deal of humor and appreciation for the downright ridiculous is why she remains one of my favorite cartoonists, period. Allow me the luxury of suggesting you make her one of yours as well. •

Featured image by Isabella Akhtarshenas. All other images courtesy of Fantagraphics.