My first real memory may very well be the opening scene from Star Wars: A New Hope, in which, after the floating text tells us the world is at war, Darth Vader and his stormtroopers seize Princess Leia’s ship. While rebel soldiers line the hallways, stormtroopers blast open the air-locked door and begin firing lasers. A moment later, Vader comes through with his black mask and heavy breath, cape sweeping the ground behind him, and sometime after that we see lightsabers and landspeeders, X-wing and Tie-fighters, the Millennium Falcon and the Death Star, and I’ll say now “ignite” is too weak a word to apply to what that movie did to my imagination.

Suddenly we were all looking at the stars, wondering what went on above our heads. Or we were arguing if lightsabers were real, if we could learn to use the force to move things with our minds or convince our mothers to take us swimming if she said no the first time. I still wonder, occasionally, when I’ve left a light on after climbing into bed, if I couldn’t just turn it off with the wave of a hand.

The second word in the movie title is war, and we played at it constantly. At Christmas, cardboard wrapping paper tubes turned into lightsabers. My mother’s station wagon morphed into the Millennium Falcon, and any truck following too closely was a Tie-fighter. On summer nights, lightning strikes might have been a battle above us, thunder the crash of star destroyers or Death Stars.

We also collected all the characters. My brother and I pooled our allowances to buy the action figures, then set them up against one another on the floor of our room. Stormtroopers murdered Jawas. Sand People rose from the rocks and struck Luke Skywalker. Han Solo shot Greedo, and Obi-Wan chopped off that walrus-guy’s arm before being killed in the end by Vader. We made them fight until we grew afraid. Alderaan got annihilated. The Death Star was destroyed.

It seems there was so much to be scared of in the late ’70s. Bombs fell constantly at nearby Fort Chaffee, as if the army were gearing up for war, and in 1979, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan. In September of the same year, the U.S. discovered a Soviet combat brigade in Cuba and refused to ratify the Salt II agreement, which would have limited the number of nuclear missiles on both sides of the world. I only heard the rumblings then, looking as I was to the skies, but I could feel it beneath the floors of my shoes when the bombs struck.

The year after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, The Empire Strikes Back came out. Critics claim it the best film in the series, but I left the theater sick to my stomach. Han Solo was taken captive by Boba Fett after being betrayed by Lando Calrissian, who was in turn choked by Chewbacca. Luke lost his hand, and worse still, we learned Vader was his father. The whole galaxy, it seemed, was collapsing.

By the time Return of the Jedi was released in 1983, the world was close to war. In September, not long after the movie premiered, a Soviet Su-15 shot down a Korean airliner with an American congressman on board. Less than a month later, a Soviet early warning system falsely detected the launch of American Minutemen missiles, and the world hovered on the edge of annihilating itself. Some of us were still watching the skies, worried that what we saw on the movie screen might not be make-believe.

That same year — I was 11, my voice close to dropping into the serious tones of a man — President Reagan announced his Strategic Defense Initiative. To save the United States from the evils of the Soviet Union, we would put lasers and interceptors in space to shoot down Soviet missiles in case of a nuclear attack. Because of its reliance on futuristic technologies like lasers, subatomic particle beams, and electromagnetic rail guns, the SDI was nicknamed Star Wars, although the animation that ran on our TV screens of how it would work was much less realistic than any movie.

I don’t know if we grew older and forgot childish games because the real world colored our view of the movies, but shortly after Reagan’s announcement on national television, my brother and I burned all our Star Wars figures. We lined them up on a rock wall behind our house and held a lighter to a can of hairspray, creating a flamethrower. We watched their faces melt, the same way TV shows such as The Day After assured us we would melt when the missiles flew and the warheads landed after the lasers in space failed to stop them. Perhaps we knew then that despite that opening line of “a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away . . . ” that here was our future: men like the ones we would someday become continuing to build missiles and lasers and lightsabers and Death Stars, until all the universe was destroyed.

In the seventh Star Wars movie, The Force Awakens, a new war begins. A weapon even more powerful than the Death Star, with the ability to destroy five planets, has been built, and a small band of rebels must destroy it. Some critics have complained the movie is simply a reiteration of the other ones: the same threats, the same weapons, the same heroes, and it’s hard not to argue that history repeats itself, even in movies.

At the end of the eighth movie in the saga, Rogue One, everyone dies. The Death Star fires from the skies and a massive tsunami washes over the rebels. Two of the main characters sit on the beach in the last sunset of their lives. A moment later, time loops around and again Vader invades the rebel ship. The movie ends where my childhood began: the world is at war, Vader is breathing heavily in his black mask, and there’s only a tiny sliver of hope that the evil Galactic Empire will ever find defeat, or that men will ever stop attacking each other.

One thing the Star Wars universe lacked was cost. There was never any cost to use the force, unless it was the evil that overcame the wielder if he used it in anger. The only limit was what he could imagine, and I wonder now how much war we can imagine, how much all our warring will cost us. I wonder how we would use the force today, if we would choke all the enemies who came at us, or destroy the Death Stars we’ve already put in space.

In our world, what we call the real world, forgetting how art imitates life, the sky is full of interceptor missiles, the descendants of Reagan’s Star Wars program. The United States has invaded Afghanistan; we’ve been there longer than the Soviets ever were. The old Soviet Union no longer exists, but there’s evidence Russia hacked the 2016 election, that they’ve engaged in a new kind of war. Trump recently announced an initiative to build a state-of-the-art missile defense system to combat what he fears might fall on us out of the sky. Along with the initiative to put missiles among the stars, he also announced a Space Force, modeled after the Marine Corps, which includes changes to the Air Force to bolster national space security. This outer space security concern stems from the fear the Russians might get there before us, which makes me think of Reagan, and my Star Wars figures, how my brother and I burned our little green army men first, then turned our attention to the stars.

With more movies on the way, the Star Wars universe is as strong as ever. As is the idea that we can protect ourselves by placing defenses in outer space, which reminds me I’m still afraid of the same things I was when I was a child. Some days I think the movies are real, and we’re watching the last hour of humanity. You’ll have to decide if there’s any hope. •

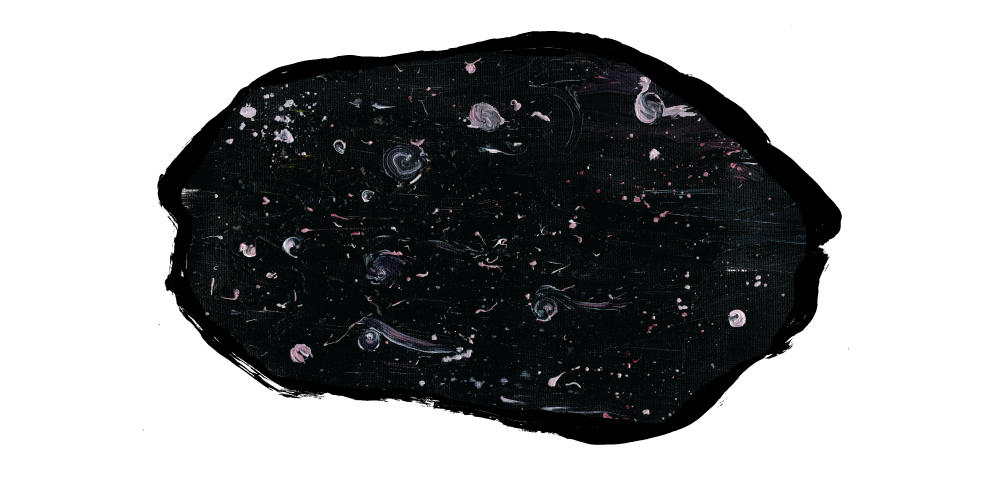

Illustrations created by Emily Anderson.