Maybe you’ve been lucky enough to be in Venice. You’ve seen the party-colored palaces that line the Grand Canal. You’ve sat at a table in the Piazza San Marco enjoying an aperitivo at Florians or lunch at Harry’s Bar, thinking this is how Hemingway felt. You’ve run your hand along the smooth sensuous marble interiors of churches and stood in awe before the art on the walls around you. You’ve done your best to hit as many high spots as possible that are mentioned in the travel books. But if that’s all you’ve done, you haven’t seen Venice.

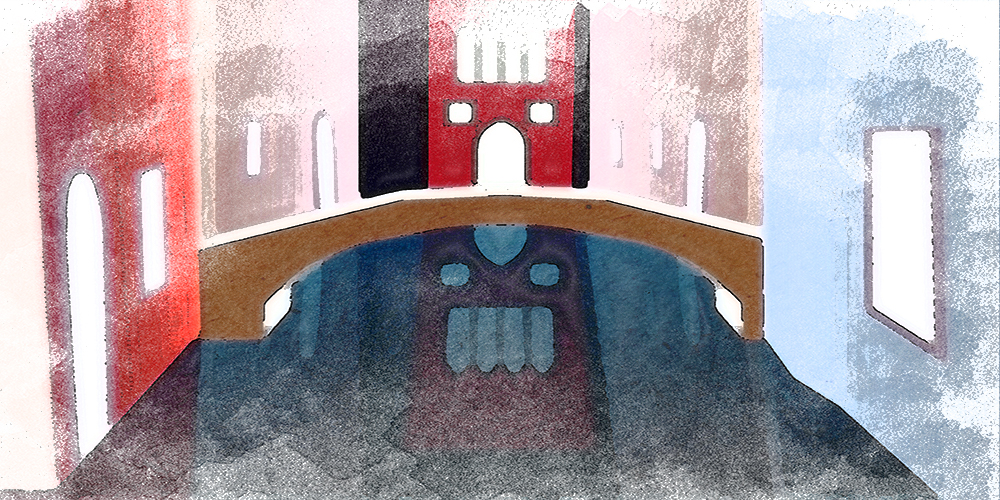

To really see her you have to stand beside the Grand Canal in early morning when the tethered gondolas are floating on their own reflections and bridges are hanging upside down in the water. You have to go back at midday when the pink and white of palaces are melting into the rose and cream of freshly made gelato. And then again at evening when the sunlight is slanting against the Grand Canal, colors beginning to drip into each other as water and sky draw closer in an embrace of elements, the tide swelling and moving farther into the belly of the city, the rising water lapping at the thick wooden piles, sucking them deeper into the slushy sand. Night in Venice is the ultimate wet dream.

Venice is not mortar and stone but light and water and atmosphere. Her face doesn’t fix in your mind for all time but changes according to the hour, the month, the season you pay her your respects, and who you are. To politicians and economists, she is the greatest Mediterranean military and commercial power after the fall of Rome. To painters, she is Giorgione, Titian and Tintoretto. To architects and sculptors, the Piazza San Marco and the Doge’s Palace. And to pleasure-seekers, Casanova and carnival.

Authors too, like courtiers, have worshipped at her court. Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice and Othello, Henry James’s The Aspern Papers, Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice and Hemingway’s Across the River and into the Trees are just a small portion of the hundreds of fictional works she has inspired. No less ubiquitous are the travel logs, diaries and memoirs that have extolled her beauties: e.g., Goethe’s Italian Journey, Gautier’s Travels in Italy, Howells’ Italian Journeys, Dickens’ Pictures from Italy and Rusk in’s three-volume The Stones of Venice.

But for all her shifting faces, the one that never changes is that of the Eternal woman in all her moods and mysteries — charming, vibrant, with an emotional depth that is never fully sounded, the mature woman who has known life in all its twists and turns, and the femme fatale, so seductive and alluring that once you have seen her nothing else matters. 19th-century Italian author Gabriele D’Annunzio said it outright in his novel, The Flame of Life: “Do you know, Perdita, of any other place in the world like Venice, in its power of stimulating at certain moments all the power of human life, and of exciting every desire to the point of fever? Do you know of any more terrible temptress? ”

By the 18th-century, when her military and commercial preeminence had come to an end, Venice went into denial. Retreating behind the anonymity of masks, she turned carnival into a six-month festival. Idleness, gambling, and debauchery became the pastimes of all who could afford the price of a false face as if she knew in her prescience about the coming of the most notorious Romantic figure of the nineteenth century.

In 1816, all England and most of the Continent were aflame in the white heat of Lord Byron’s poetry and his exploits. Men wanted to be him, women, to be taken by him. But when marriage difficulties, exacerbated by rumors of incest with his half-sister Augusta, became too much to bear, Byron cursed the hypocrisy of regency England and fled to Geneva where he stayed briefly before settling in Venice. There, from 1816 to 1819, he lived on the Grand Canal with 14 servants, two monkeys, two dogs, a fox, and a varying number of female companions while continuing to send cantos of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage to his publisher in England. Four years earlier when the first two cantos of the poem were published, 500 copies sold in three days, prompting his famous quip, “I awoke one morning and found myself famous.”

No sooner did Byron arrive on Venetian shores than an apparently endless stream of Venetian ladies lined up to “take the measure” of the famous English poet, who was only too happy to accommodate them. Inspired by, or in spite of, this enervating amorousness, Byron continued to write poetry, including the entire fourth canto of Childe Harold. In it he remembers his youthful infatuation for Venice that has not diminished even in “her day of woe:”

I loved her from boyhood — she to me

Was as a fairy city of the heart,

Rising like water-columns from the sea,

Of joy the sojourn, and of wealth the mart;

And Otway, Radcliffe, Schiller, Shakespeare’s art,

Had stamped her image in me, and even so,

Although I found her thus, we did not part,

Perchance even dearer in her day of woe,

Than when she was a boast, a marvel, and a show.

Perhaps Byron saw in Venice the mirror image of himself, the beautiful, famous personage admired by all the world, still proud, still beautiful, but fallen into degradation and decay. Perhaps he and Venice were the two halves, male and female, of the primordial being separated in lost time, now at last having found each other. In Teresa Guiccioli, his last mistress, Venice gave him the love he had found nowhere else and the courage for what lay ahead for him in Greece.

53 years later, the great British-American author Henry James followed in Byron’s footsteps. In his collected essays on Italy, published later as Italian Hours, he described Venice in language that, for James, borders on the erotic:

It is by living there from day to day that you feel the fulness of her charm; that you invite her exquisite influence to sink into your spirit. The creature varies like a nervous woman, whom you know only when you know all the aspects of her beauty. She has high spirits or low, she is pale or red, grey or pink, cold or warm, fresh or wan, according to the weather or the hour. She is always interesting and almost always sad; but she has a thousand occasional graces and is always liable to happy accidents. You become extraordinarily fond of these things; you count upon them; they make part of your life. Tenderly fond you become; there is something indefinable in those depths of personal acquaintance that gradually establish themselves. The place seems to personify itself, to become human and sentient and conscious of affection. You desire to embrace it, to caress it, to possess it; and finally, a soft sense of possession grows up and your vision becomes a perpetual love-affair.

In another letter to a friend he rhapsodizes:

The simplest thing to tell you of Venice is that I adore it — have fallen deeply and desperately in love with it. I had been there twice before but each time only for a few days. This time I have drunk deep, and the potion has entered my mind.

On and off for 38 years, James returned to Venice, unable or unwilling to get his fill of it. By the time of his final trip in 1907 most of his friends from previous trips were dead, and those that weren’t made him feel so out of place that he “could never again face the irritation and inconvenience of it.” But Venice itself had not changed for him; her gossamer threads were as tightly wound around his heart as ever: “never has the whole place seemed to me sweeter, clearer, diviner.” When he left her for the last time and returned to New York, he confessed openly to his friend, Edith Wharton: “I don’t care if I never see the vulgarized Rome or Florence again — but Venice never seemed to me more lovable.” James too had pledged his allegiance to his sovereign.

Henry James’s life of family wealth, private tutors, and world travel predisposed him to the traditions of Old Europe that he so admired. Mark Twain, his contemporary, grew up in the backwater hamlet of Hannibal, Missouri, population approximately 700. Where James was eminently comfortable amid old-world traditions, Twain saw them through the eyes of a satirist. To him, they were the remnants of a decayed system that kept the wealthy in power at the expense of the middle class and the poor. Twain was the quintessential American who believed in hard work, fair play and equality, James the natural-born American who traded his birthright for British citizenship.

Like James and many others of the 19th and 20th centuries, Twain made his version of the Grand Tour to Europe in 1860, later publishing his impressions in the first of his three travel books, The Innocents Abroad. While not oblivious to the natural beauties of the country or to its ubiquitous art, he found “too many churches,” “too many well-fed priests” and an overall indolence among the people that flew in the face of good old American values. Even Venice did not escape his disdain:

Her glory is departed . . . she sits among her stagnant lagoons, forlorn and beggared, forgotten of the world. . . a peddler of glass beads for women, and trifling toys and trinkets for schoolgirls and children.

But his penchant for humor and satire notwithstanding, Twain was able to look deeper and, like James and Byron before him, see the substance beneath. All humor and satire aside, he was a truth-teller to the end. His description of drifting down the Grand Canal is not that of an iconoclast hurling insults but of a Romantic who succumbs to the same enchantments that continue to seduce millions:

In a few minutes we swept gracefully out into the Grand Canal, and under the mellow moonlight the Venice of poetry and romance stood revealed. Right from the water’s edge rose long lines of stately palaces of marble; gondolas were gliding swiftly hither and thither and disappearing suddenly through unsuspected gates and alleys; ponderous stone bridges threw their shadows athwart the glittering waves. There was life and motion everywhere, and yet everywhere there was a hush, a stealthy sort of stillness, that was suggestive of secret enterprises and bravoes and of lovers; and clad half in moonbeams and half in mysterious shadows, the grim old mansions of the Republic seemed to have an expression about them of having an eye out for just such enterprises as these at the same moment. Music came floating over the waters — Venice was complete. It was a beautiful picture — very soft and dreamy and beautiful.

In the pantheon of English travel writers that includes such immortals as H.V. Morton, Norman Douglas, Lawrence Durrell, and others, Jan Morris is secure. A Welsh historian known especially for her Pax Britannica trilogy, a history of the British Empire, she has written books about many of the world’s great cities. Morris has rejected the description of herself as a travel writer, preferring the term “writer of places.” It’s a title she richly deserves. No one has delved more deeply into the poetry and the psychology of cities than she has.

Her book, Venice, described by her as “a record of old ecstasies,” takes the reader into the heart and soul and history of Venice as few authors, with the possible exception of Henry James, ever have. Morris too seems most comfortable describing Venice as one would describe a woman:

The Venetian allure is partly a matter of movement . . . her motion is soothing and seductive. She is dressed in breathtaking brocade and silk. She is yielding . . . even the mud is womb-like and unguent.

For Morris, Venice is not a place you see and then move on from to something else. You can leave Venice, but Venice refuses to leave you. She stays with you, always nudging at your shoulder, her unique braiding of Moorish, Gothic and Renaissance architecture following you like a persistent melody or a dream that has twined about your consciousness and will not let go:

Wherever you go in life, you will feel somewhere over your shoulder a pink, castellated shimmering presence, the domes and riggings and crooked pinnacles of the Serenissima.

Truman Capote, the American novelist and short-story writer, took all of 13 words to evoke the sensuality and voluptuous abandon that Byron, James, Twain, and Morris surrendered to in Venice, but he did it in his own inimitable way: “Venice is like eating an entire box of chocolate liqueurs in one go.” •