Cultural critics generally place themselves at a distance from material culture. They may critique the world, but they don’t seem to inhabit it.

But why shouldn’t those of us who parse culture also celebrate it — acknowledge that we make choices all the time about the clothes we wear, the food we eat, the furniture we put in our homes? Why shouldn’t we, in other words, make recommendations regarding products and services that we think are unique, useful, or otherwise commendable?

“We’re IN society, aren’t we, and that’s our horizon?” as Henry James put it. In a consumer society, we want reliable recommendations regarding products that can improve our lives. At the same time, we tend to be suspect of product endorsements. We are aware that advertisers will use whatever means they can to sell — from testimonials by famous people to ingenious product placements to the incorporation of skepticism itself into their messages (i.e. couturiers who stitch “waist of money” into their garments). But if someone like myself, who has experience deconstructing culture, sets out to explain the value of a product, shouldn’t that carry weight? I realize, of course, that this could be seen as a more sophisticated advertising ploy, but that’s the mise en abyme of salesmanship and a risk you have to take.

In this case, I want to endorse a product that may save the reader a great deal of money. I also want to probe what this product and its potential savings may mean. Is the need for the product a “real” need and are the savings a “real” boon when looked upon in a wider or at least a different context?

So to get to it.

I wish to extol the Wonder Cloth, a product I purchased for $9.99 about seven months ago at the large chain store, Bed, Bath and Beyond. I am not employed or otherwise connected to Bed, Bath and Beyond. I receive, as many people do, the store’s 20% savings coupons in the mail and use them when I go. Other than that, they have not done anything special for me and in no way asked me for an endorsement. The Wonder Cloth is not even their product; they merely stock it. You can buy it online for even less money, as a quick search indicates. Moreover, the cloth is advertised as a makeup remover, not as a miracle skin treatment, the purpose it has served me, as I shall explain. I should add that there are other products out there that are similar. The MojaFiber cloth, for example, comes in a three-pack costing $19.99. These also work well, though I prefer the Wonder Cloth, perhaps out of brand loyalty, having stumbled upon it first.

As background to my endorsement of the Wonder Cloth, I should explain that, before discovering it, I had spent hundreds of dollars a year on skin care products. If you also factor in dermatologists and facial treatments, the expenditure rises into the thousand or so dollars. Considering that my concern about my skin has existed since I was a teenager and extends from there over a period (rounding off) of 40 years, I would estimate that I have spent $40,000 on my skin. This may sound like an overstatement but consider that the New York Times Style section did a feature on a men’s moisturizer that costs $75. That’s just a moisturizer — and for men. In other words, my estimate is modest compared to what other people, even men, may be spending on their skin.

So compare my expenditure of $40,000 on skin care to $9.99 for one re-usable cloth (or, taking into account wear and tear, an extra one for travel, and the disappearance of a few, along with socks, in the wash, let’s say $100, had this product been available to me from the beginning). In short, a substantial saving. This is all the more impressive when I say that the results of the $40,000 expenditure were lackluster, while the results of the $100 expenditure have been astonishing.

But let me dig a little into the ontology of skin care before going further.

Why, you might ask, would people spend hundreds if not thousands of dollars a year on their skin? Because, I would answer, they have bad skin. To be fair, my skin was never that bad, just moderately bad. I imagine that there might be people in the world for whom my complexion wouldn’t have given them a second thought.

But from my rather extensive knowledge of women — and my admittedly smaller insight into men — most people with moderately bad skin are concerned about it.

This is why dermatology is now among the most competitive (i.e. lucrative) medical residencies: the “D” in the so-called ROAD specialties.

The skin is the largest organ, that part of ourselves that faces the world, and hence the first thing that others come to judge us by. Its capacity for metaphorical significance is considerable (one talks of people being “thick-skinned” or “thin-skinned”). I won’t go into racial history where skin color has been the basis for the inhuman treatment of whole races of people. Or the way the illness of leprosy was for centuries connected to sin and moral decay. Rosy, alabaster, porcelain — such terms are almost reflexively associated with female beauty in Western culture, amended more recently to include creamy milk chocolate and black velvet. I have yet to find a poet extolling the pebbly, the mottled, or the carbuncular.

My skin problem dates back to junior high school, an age when physical self-consciousness is at its peak. I’ll never forget the mortification I felt reading the General Prologue to Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales in 9th grade when we arrived at the Summoner’s “fire-red face,/So pimply was the skin” — for whom “no ointment” could “rid his face of even one white pimple/Among the whelks that sat upon his cheeks.” I was sure that everyone was staring at me.

Had my complexion been clear, I have no doubt that I would have been more outgoing, gone out for sports, and had many more friends. I might have run for student council and had a political career. I attribute my life in academia to the fact that reading allowed me to bury my nose in a book rather than parade it outside where people could scrutinize my complexion. As it was, huge swaths of my time were spent daubing my face with various solutions, covering it with pasty products that were supposed to both mask and improve it, and trying not to catch a glimpse of myself in store windows.

I continued to have mild acne into my 20s and 30s, and then graduated to a more mixed complexion — dry patches and oily, in my 40s and 50s. From a distance, and even at relative proximity, my skin was not bad after I reached full maturity, but if you looked with attention, you saw that it was not good either. Few people looked with attention, of course, but that didn’t prevent me from imagining that they did. If you’ve had bad skin in youth, you never outgrow this kind of self-consciousness.

After college, I began to seriously investigate the world of skin care. Living in New York City, I had access to the great department stores and would linger at counters until snagged by women with excellent complexions who would assure me that if I used their products my skin would be like theirs. This was also the period when facials began to be popular. I can still recall Elizabeth Arden’s red door on Fifth Avenue where I spent half my meager salary — though their treatments mostly made my skin worse. The search continued for decades, and resulted in various regimens, involving cleansers, toners, pore-minimizers, moisturizers, retin-A cream, and other emoluments that crowded my sink and medicine cabinet, and which I used erratically or, after a few trials, not at all.

Then, this year, I stumbled on the Wonder Cloth while looking for a soap dish in Bed, Bath, and Beyond. This square of microfiber cloth when immersed in warm water and rubbed with moderate vigor on my face completely did away with all the problems that had plagued me over the years. It erased the dry patches and forehead eruptions, reduced the pores and redness, and, after only one use, created a smooth, healthy glow that I had never before encountered in the vicinity of my face. This was accomplished without soap or any of the product-additions that I had been sold over the decades.

I have used nothing on my face for seven months now besides warm water and the Wonder Cloth, with the exception of a light foundation to cover some of the indelible marks of acne and age.

This raises the issue of how it could possibly be that a small swath of material could be more effective than the most expensive products and treatment regimens. Is this a miracle? And if so, why would a miracle happen on such a small scale? Why not have the miracle be associated with alleviating global warming, world poverty, or cancer? Actually, there is something akin to the Wonder Cloth for a particular cancer — it’s called Gleevec, generic name: Imatinib. Wikipedia it. But that’s the subject of another essay.

Perhaps more germane than the question of what the Wonder Cloth says about miracles is what it says about consumer culture.

For one thing, it demolishes the old saw that you get what you pay for. It also says that sometimes the simplest treatment can be the best, and that so-called experts may not know things that are staring them in the face. These insights are not new. I was told them for years by my mother. It’s just that we rarely get a dramatic example of their truth. The Wonder Cloth has empowered me to look at the world with new eyes.

For example, the simple recipe that I can get off the corn flakes box may actually be tastier than the complex one in the Julia Child cookbook. And there may be a commonsensical way of raising children that does not require that I consult a Ph.D. in child psychology.

These are not, I realize, exact analogies to the Wonder Cloth. I’m still waiting for other sorts of remedies that are more analogous — like a simple way of losing weight that involves, say, eating a bowl of kale every day (this is hypothetical, I am not endorsing it); or of getting rid of unwanted hair (I thought there might be one in a product called the No-No, but I couldn’t get it to work).

You may ask if the Wonder Cloth is selective in its effects. Does it only work on me? I haven’t done an extensive clinical trial, but my daughter, to whom I sent one, also swears by it, and she has sent it to some of her friends, who seem to like it too. But I am surprised that there has not been a groundswell of interest in this product. Perhaps its modest claim to remove make-up rather than to solve all complexion problems, not to mention its dumpy packaging, have kept it under the radar. Perhaps this essay will go viral and inform the larger world.

By the same token, the product does have a downside. I look back at the years of searching for skin products with mixed feelings. It was a thankless and expensive search, but it was also a pilgrimage. It had the quality of a holy rite, quixotic in its seeming impossibility. I miss that Sysiphean quest. I suppose this is akin to someone who leaves prison and misses living behind bars. But the fact is that I enjoyed talking to those women in their white lab coats at the department store make-up counters; and I have thought about how an entire industry would be destroyed if the Wonder Cloth were to truly catch on. I also acknowledge that I would never have read so much — or had the patience to write so much — had I not been confined indoors by my bad skin.

The discovery of this product has also opened up vistas of free time. What used to take hours ministering to my skin now takes minutes. When I think of the time spent on my skin over the past decades, I think of what I could have done with it — written ten books, learned Mandarin, become an expert in wines and beers — but it seems rather late in the day to do those things now. And the time that has been opened up weighs heavily.

Interestingly, however, I have lately begun to notice other parts of my body that I previously ignored and that seem to need attention. A few months ago, I began to look askance at my nails. I had never given them much thought before. Nails are not as front and center as skin, but now I realized that mine were short and raggedy and that it would be nice to paint them red. I decided to get a manicure, which I have continued to do for several months now. This takes time and money. And having read about the exploitation of manicurists, I seek out those that seem more legitimate and hence more expensive. I should note that a seemingly miraculous remedy for creating beautiful nails that would last unchipped for weeks — the so-called gel manicure — proved not to be one for me as it almost destroyed my nails. Regular weekly manicures had to do.

This, then, seems to be the nature of how things work in a consumer culture. Saving money in one area shifts the expenditure to another. The time opened up by an easy remedy makes time for a more time-consuming one; fulfilling one need leaves room for the creation of new ones. The economy chugs along, and though my skin is clear and my nails under control, I have begun to notice that my hair needs a lot more work. •

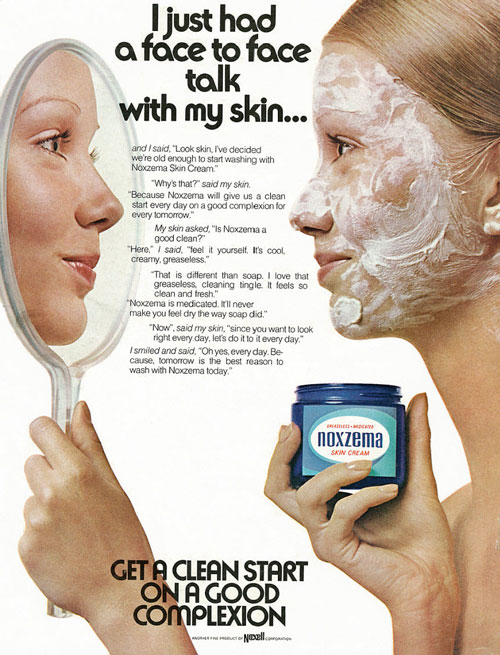

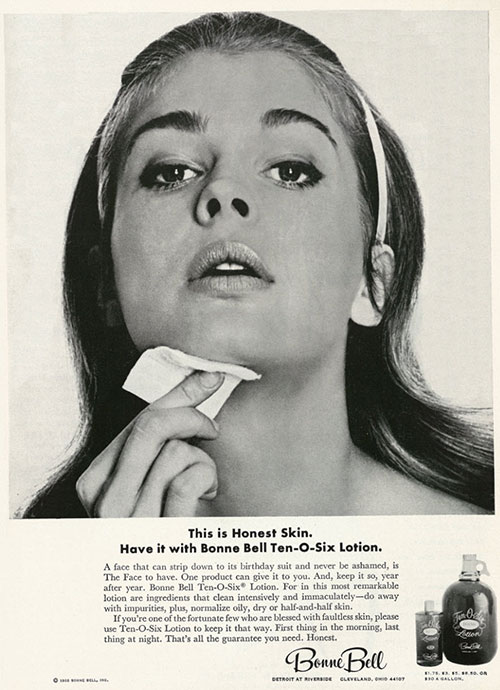

Vintage ads from Addie via Flickr and Classic Film via Flickr (Creative Commons).