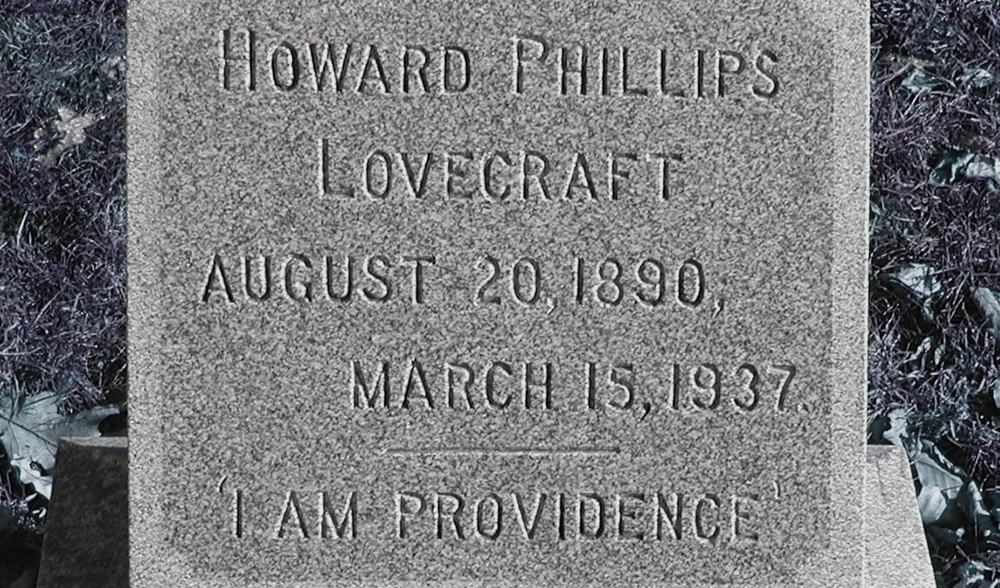

I am not a fan of H.P. Lovecraft. I have attempted a number of times (well, OK, two) to delve into the seminal horror author’s work and each time found myself unable to proceed very far. Whatever merits his prose might possess, I have repeatedly found his stories overly written, overly mannered, devoid of compelling characters, and incapable of producing believable dialogue. And then there’s all that racism.

That being the case, you would think that something like Providence, the recently finished 12-issue comic by writer Alan Moore and artist Jacen Burrows, would hold no appeal for me, seeing as it delves heavily into Lovecraftian mythos, to the point where the author himself appears as a significant character. How could I possibly find enjoyment out of a comic that is pretty much a treatise on an author I really don’t care much for?

And yet I did. Regardless of whatever misgivings I might have about Lovecraft’s place in the literary canon, I found Providence to be a compelling, if disquieting, comic, one that speaks to both our current era and American history as much as it does the unspeakable horrors that Lovecraft dreamed up.

Burrows’s name is probably unfamiliar to you, but I’m hoping that Alan Moore needs no introduction. The British author made a name for himself way back in the 1980s, where he turned familiar comic book tropes and genres on their heads in titles like Miracleman, V for Vendetta, and D.C.’s Swamp Thing. His best-known and most well-regarded work is easily Watchmen, a self-contained superhero whodunit that pointed the way — along with a few other late-’80s works like Dark Knight Returns and Love and Rockets — to creating sophisticated, layered comics for a more adult audience. His influence can still be strongly felt in most of the mainstream (i.e. superhero) comics being produced today.

Having forsworn Marvel and D.C., he’s spent a good bit of his career in the ensuing years working on more personal projects that explore occultism and magic (Promethea) and, relatedly, the symbolic power of fiction and storytelling (League of Extraordinary Gentlemen). A practicing ceremonial magician, Moore has advocated the notion of a collective unconscious of sorts, composed of ideas that anyone can access and utilize. For Moore, the creation of art is literal magic in and of itself, so it’s no surprise that Providence contains of all of these elements.

Providence is actually the final (or is it first?) chapter in a trilogy of sorts, one that began with The Courtyard, a Lovecraft-themed prose story Moore wrote in 1994 and that Burrows and Antony Johnston adapted into comics back in 2003 for publisher Avatar Press. Moore and Burrows followed that up with Neonomicon in 2010, a dark, mean comic featuring a modern female detective who runs afoul of some Lovecraftian cultists who are keeping . . . something in their basement. Providence tells the story of what came before these two tales and then wraps everything up in a nice, apocalyptic bow. Keeping all that in mind, readers would be better suited to peruse those works, more than Lovecraft’s, before jumping into Providence. (Avatar just funded a Kickstarter-backed project that will collect all three series into one slipcased set, due out in October.)

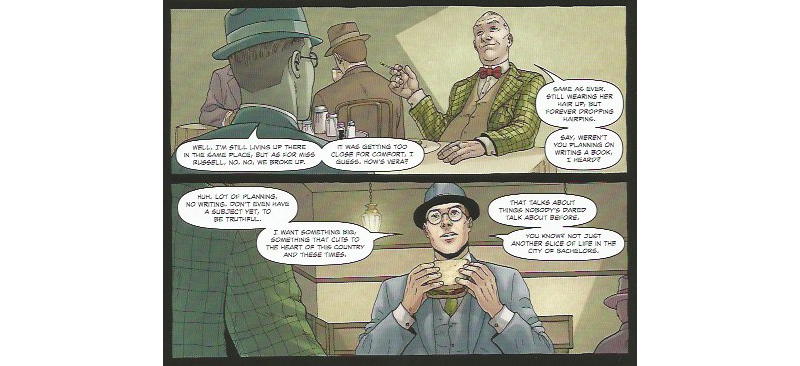

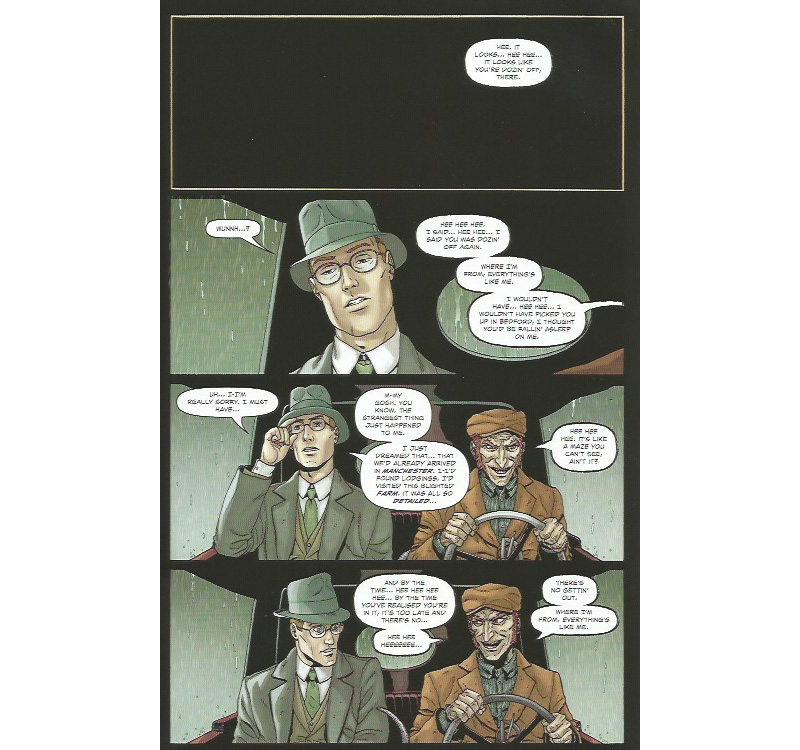

Providence takes place in 1919, in an America very much like our own but with subtle differences, such as “exit chambers” — small, domed buildings where people can go to commit suicide. It is in one of these structures that the spurned lover of New York City newspaper reporter Robert Black, a Jewish, closeted gay man, kills himself. Shaken by the tragedy and imbued with a desire to be a writer of no small importance, Black decides to suppress his grief by taking a trip up to New England, ostensibly to get research for a potential novel about a hidden America, one that perhaps has dealings in the occult or a secret society or two.

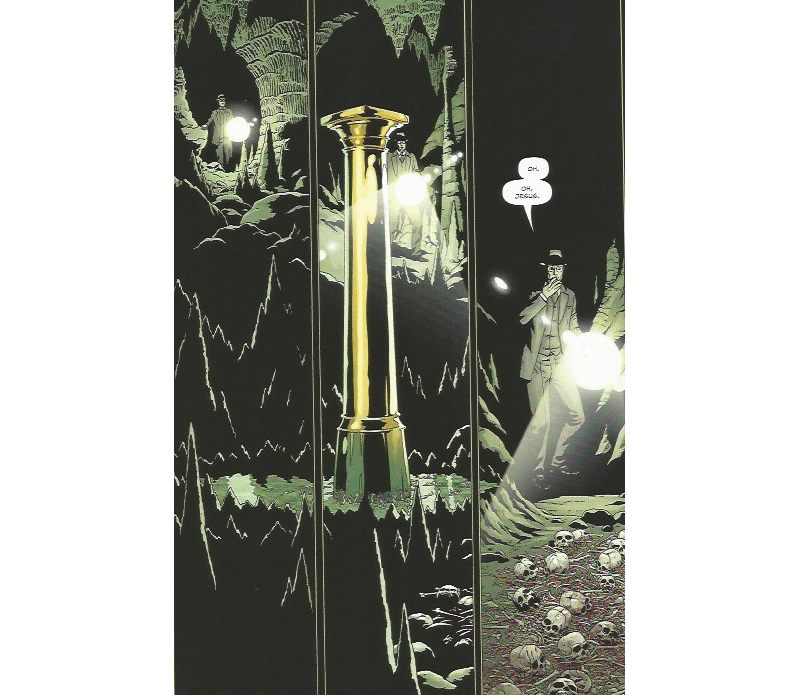

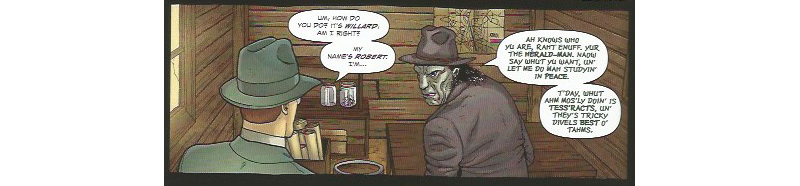

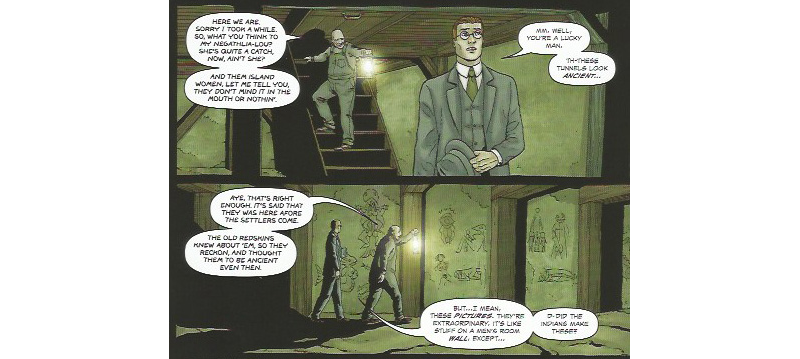

Of course, it isn’t long before Black comes across a more gruesome and nefarious “hidden America” than he had initially suspected, although it takes him a while to fully realize what he’s actually encountered. Each stop along Black’s trip brings him into contact with various characters from Lovecraft’s stories. The names are changed, mind you, but they all correspond to the characters in Lovecraft tales like The Shadow Over Innsmouth or The Thing on the Doorstep. (And while I maintain that knowledge of these stories is not necessary to enjoy the comic, I should note there is a very helpful website that provides annotations for each issue/chapter, so you can know exactly which story is being referenced when.)

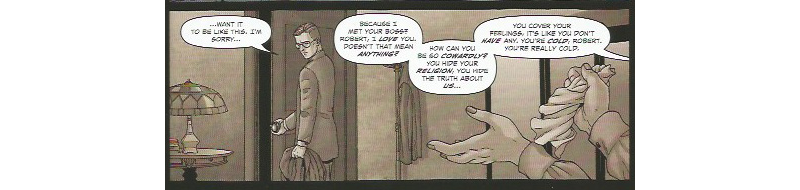

As mentioned, Black is no stranger to secrets, hiding his “true self” (Jewish, homosexual) from most of the outside world and only dropping his guard among a chosen few members of his own “secret society.” But he’s not as much of an outsider as he likes to think. Indeed, as we travel with Black, we realize how unsympathetic a protagonist he is at times. Beyond his cruel and cowardly rejection of his lover (shown in flashback), Black frequently comes off as snobbish and insultingly dismissive of those he considers intellectually inferior (exemplified in the prose passages excerpted from his diary or “commonplace book” at the end of each chapter). He’s also often rather clueless as to the true motives of the folks he meets (in true Moore doublespeak, everyone keeps referring to him as “the Herald,” which he takes to mean the newspaper he used to work at, even when it’s quite clear they don’t). Black encounters a good deal of bigotry and even downright repulsion towards some folks in his travels, but it is not as though he himself is immune from those behaviors. The fact is that in his general attitudes and prejudices, Black is as much a part of “normal” society as he is separate from it.

Indeed, this idea of what it means to truly be an outsider (Is it Black? Or the monsters he encounters?) suffuses Providence. One of Moore’s stated intents with both Neonomicon and Providence is to bring to the fore the sexual, racial, and xenophobic issues that dwelt unspoken at the heart of Lovecraft’s work. Lovecraft might have seen himself as a man out of time to some degree (his abhorrence of modern literature is well known), but though he was perhaps more expressive in voicing his racism and antisemitism than his contemporaries, it wasn’t as though such opinions were out of sync with the times.

Throughout the trilogy, Moore pushes this subtext to the fore, especially as it pertains to sex and sexual violence, often to uncomfortable and upsetting places. Neonomicon, for example, features an extended and horrific rape sequence. Providence has two instances of sexual assault, one particularly harrowing example located at exactly the midway point of the story. A third, incestuous incident is alluded to in passing. (Providence is restrained in its gore, but it certainly pulls few punches, so caveat emptor.)

Another of Moore’s stated goals with Providence is to find a way to make Lovecraft seem scary again, perhaps a more difficult task than you might think given that plush Cthulhu dolls are easily available for purchase these days (and indeed several are prominently placed in both Neonomicon and Providence). “I think what is perhaps needed is an effort to refocus the readership’s attention upon the things that are genuinely frightening or disturbing about Lovecraft’s writing,” Moore said in an interview last year, “such as his ruminations about our probable flight from knowledge and complexity, rather than on how cool a beard of tentacles looks.”

It’s that “flight from knowledge and complexity” that gives Providence a haunting correlation with our contemporary culture and politics. As the chaos (spoiler alert) that Black inadvertently sets loose starts to take hold of the world at large, various characters struggle in their attempt to not just process but come to terms with what they are bearing witnessing. And if their struggle to accept what by all rights should be utterly unacceptable bears any relation to Brexit or the recent presidential election (or, heck, any political event of the past few months), well, I’m sure that’s just good timing. I don’t know without rifling through my copies if anyone actually uses the phrase, “this is not normal” towards the end, but it wouldn’t surprise me if they did.

In many ways, Providence is the flip side of the coin to Moore’s Promethea, serialized from 1999 to 2005 and produced with the artist J.H. Williams. In that comic, one far more optimistic about humanity and the future than Providence, there is an apocalypse, but a benevolent one, which allows you to see people you have lost and where peace reigns. Providence similarly ends with the arrival of a new age (and there are plenty of Christian allegories made just to drive that point home), but just how benevolent its happening is depends upon whether you’re one of Lovecraft’s otherworldly monsters or not.

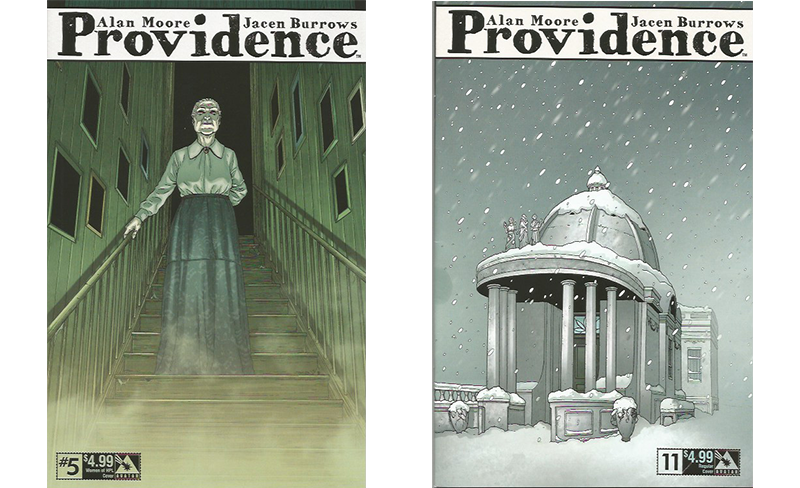

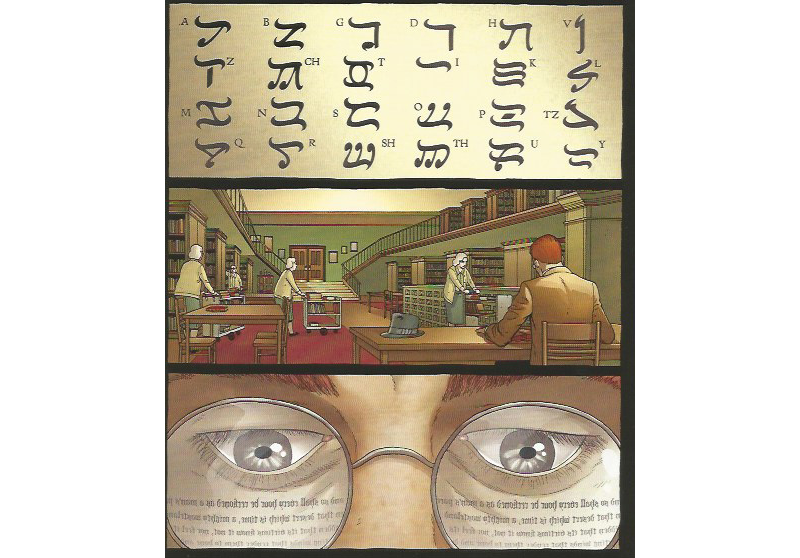

I have not yet discussed Burrows’s art work. Honestly, I was not a fan at first. Initially, I found his style cold and stiff, especially in earlier works like The Courtyard, where the characters boast weirdly elongated faces and bodies. His backgrounds seemed meticulous, spacious, and devoid of energy or warmth all at once.

But Burrows’s sterile style grew on me. He’s upped his game considerably for Providence — able to convey all the subtle and not-so-subtle emotions Robert Black and the rest of the cast go through with considerable aplomb. What’s more, his overly precise renderings perfectly match the cold tension in Moore’s text. Everything seems as it should be, but at the same time something seems a little too off, perhaps a little too neat. I can’t think of another artist doing this series justice.

Honestly, I have only scratched the surface of Providence. I haven’t yet talked about the formal structure of the book (Burrows and Moore adhere to four landscape panels per page) and how it affects your reading experience. I’ve only tangentially hinted at Moore’s core idea of how certain fictional notions (in this case, Lovecraft’s) can grow to the point where they start to take shape in the real world. I barely touched on the religious allegories. I’ll have to leave it to better, more articulate scholars, though: I’m way behind deadline.

Let me sum up thusly: The idea of “fiction as criticism” is nothing new for Moore. He’s long used familiar genres, staples, and other authors’ characters to dig at larger truths about art and society. Providence is in many ways a perfect fit for Moore for those reasons, including the fact that Lovecraft enjoyed and encouraged other writers to expand upon the universe he created. Moore has been threatening on and off to quit writing comics for years now, but if Providence does turn out to be his final turn in the medium, it’s a fitting capstone. •

Feature image courtesy of Magnus Manske via Wikimedia Commons. All images are copyright Alan Moore and Jacen Burrows.