Recently, a colleague and I were talking about television shows we watched, particularly the ones stigmatized as “bad,” “junk,” and “garbage.” She threw in a few suggestions, none of which I thought were particularly terrible – a few sitcoms and reality shows. Finally, I said, “well, I watch wrestling,” to which, she replied, “you win.” This response is not unfamiliar. As somebody who regularly watches wrestling, my fandom is frequently approached with raised eyebrows, “seriouslys,” and the inevitable “you know it’s fake, right?”

My own fandom resides in World Wrestling Entertainment (formerly World Wrestling Federation, a name change prompted by a lawsuit with the World Wildlife Fund). It is the Hollywood of wrestling. It even has its own “independent, not really” subsidiary, NXT, which airs longer matches featuring incoming athletes into the brand (some seasoned talent learning the particularities of the WWE brand and some starting their careers). There are other independent companies scattered throughout the United States that garner an enthusiastic and dedicated audience (Ring of Honor, Chikara). Wrestling has also been popular in Mexico and Japan with their own styles, narrative devices, and expectations. Programs like Lucha Underground (which is produced by Survivor exec Mark Burnett and filmmaker Robert Rodriguez) and streaming services for New Japan Pro-Wrestling (Japan’s largest wrestling company/promotion) have created developed a cultural wrestling exchange. Though I have friends who devote equal time to WWE, independent circuits, and international matches I haven’t been able to carve the time but for those matches highlighted on With Spandex, UPROXX’s wrestling site, or posted on Facebook.

I’m not sure if it’s because I’m 30, a woman, or an academic that people are confused or think I’m being facetious when I try to talk about upcoming Pay-Per-Views and storylines. It’s probably a mixture of all three. For whatever reason, it is assumed that after a reading a few books everything you enjoy must be serious and speak to elite tastes. No longer is pop music pleasurable. It’s mindless garbage and to blare Ariana Grande is a grave insult to those like Theodor Adorno who paved the way for people to not enjoy fun (popular) things.

But there are many of us academics who balk at this tradition. Wrestling has head-butted its way into academia. Conference panels have shown up at the Modern Language Association, the Society for Cinema and Media Studies, and the Popular and American Culture Association. Academic anthologies filled with intelligent discussions and analyses of performance, narrative, and industry politics exist.

Outside of academia, an influx of work has devoted space for legitimizing the study of wrestling. David Shoemaker has written and podcasted regularly about wrestling. His book The Squared Circle: Life, Death, and Professional Wrestling has become a staple for understanding wrestling as sport and entertainment. Sportswriter Bill Simmons wrote about wrestling for ESPN and recruited writers like Shoemaker and Peter Rosenberg for the now defunct Grantland website. He treated it seriously and defended the WWE vigorously against detractors. Jeremy Gordon’s New York Times piece “Is Everything Wrestling?” already articulates far better than I could about how professional wrestling has moved beyond the fringe and further into the mainstream. Linda McMahon ran for Senate. Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson has become a bonafide movie star. Wrestlers appear on Sportscenter regularly. Even presidential nominee Donald Trump is in WWE’s Hall of Fame and continues his heelwork on the campaign trail.

Wrestling is everywhere. And it’s not only for what wrestler Damien Sandow considered the “unwashed masses.”

One of the complications in approaching wrestling is sorting out what it is. Vince McMahon, Chairman and CEO of the WWE, labels it as sports entertainment, placing it in a liminal space. It does require athleticism to participate. There is little doubt about the capabilities of those performing in the ring. But unlike sports, winners are predetermined in order to further a narrative. It looks like sports, but isn’t. And many viewers aren’t necessarily interested in the process itself without the stakes of (legitimately) winning and losing. The “entertainment” comes from the narratives written for the screen, classic melodramas filled with emotional highs and lows. But daytime soaps are not considered valuable within most social circles.

There is a tension within popular culture studies. On one hand, we want to demonstrate the utility of cultural artifacts considered “low” – television, popular music, fan fiction. We spend a lot of time, however, trying to legitimize the form by looking at issues of “quality,” considering “savvy audiences,” and frequently flirt with the elitism we often try to work against. Wrestling is firmly associated with low culture. It is a physical soap opera often associated with children who don’t know better.

The most-used point against wrestling is that it’s “fake.” And this critique is said as if fans don’t already know outcomes are predetermined. A majority do. But there are plenty of things “not real.” Literature is “not real,” but we identify with characters and themes (even non-fiction can be disputed as unreal). Films are built on illusion. The phi-phenomenon creates movement out of stillness, and we enter into fantasies displayed onscreen. Even nonfiction work is the product of a series of choices made by filmmakers to construct a cohesive version of reality. But we don’t, as audience members and critics, get bogged down in the details of realness when it comes to deconstructing these texts. We know they are created and manipulated, but never as an English major did somebody come up to me and question “You know Frankenstein isn’t ‘real,’ right?”

It doesn’t matter. We remain entranced by the skills and process. The ways in which authors construct sentences, lyricists lyrics, and filmmakers shots are of significance. There is admiration for form and how that form dictates our experience, our points of identification. Pleasure exists in the struggle between creator and viewer over the narrative – who should succeed, the motivations for each character and how those dictate the course of the plot, and the ending. For some reason people (those who exist outside of fandom) seem to assume professional wrestling should be different. It isn’t.

I was once like them. When my friend told me he started watching wrestling again, I looked at him with the same disbelief. It was fine when I was younger, but I’m a grown up. What could adults get out of it? While cat-sitting, he dared me to watch Wrestlemania 30. It worked. It was at times silly, melodramatic, heart warming. Though I hadn’t watched wrestling in a decade I could immediately drop in and get to know characters and narratives. Since, I’ve done some reflection about my own interaction with wrestling and have determined three strands that have kept me invested in professional wrestling.

Count 1: Nostalgia

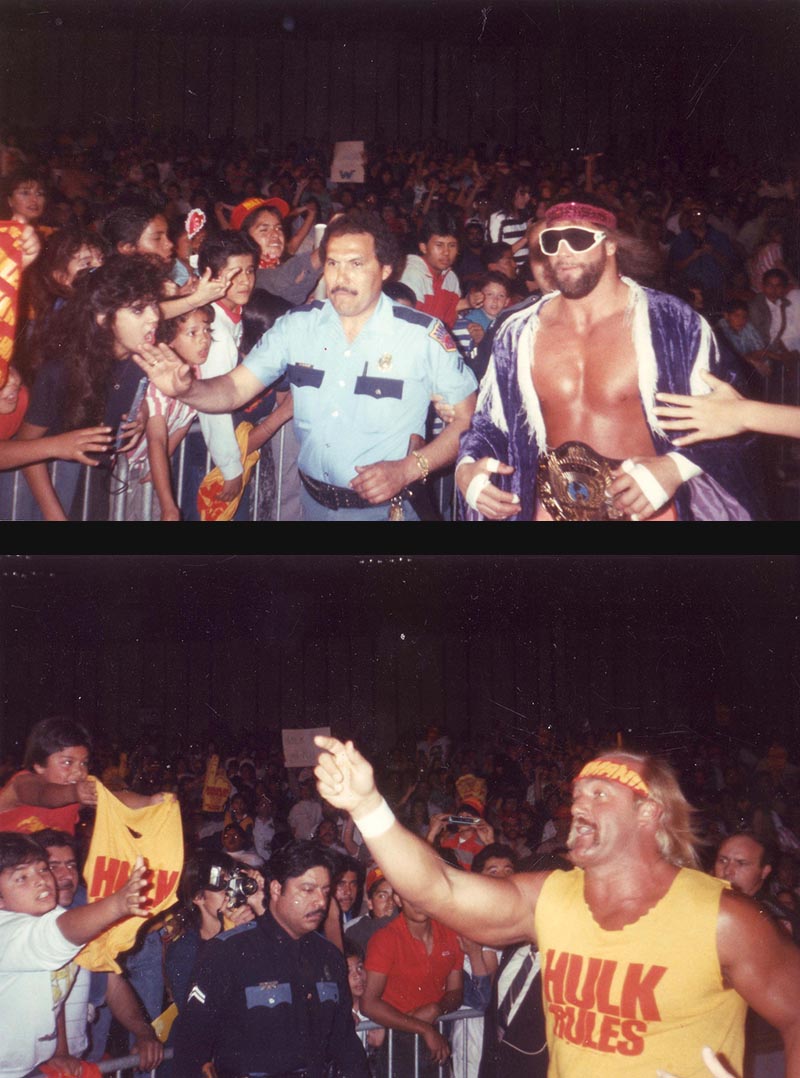

The majority of my toddler and pre-school years were devoted to wrestling. I used to move as far back as I could against a wall, bolt as fast as I could toward my dad lying on the floor, and leap into a frog splash above him. He would catch me mid-soar and pull me back to the floor. Giggling, I’d get up and like a typical only child would repeat the process until he got sick of it. Then I would turn to the tapes. VHS tapes filled with WWF episodes. Hours full of Koko B. Ware (my favorite) and Frankie (his parrot) flapping their way to the ring and Undertaker doling out pile drivers and Hulk Hogan’s ripped shirts.

As a military brat growing up overseas, wrestling was a staple for the Armed Forces Network, the military’s broadcasting service. The WWF was definitively AMERICAN. After all, Hulk Hogan ran out to “Real American,” a rockin’ jam about standing up for people’s rights at whatever cost (this is what would make his heel turn as Hollywood Hogan all the more explosive and his recent fight with Gawker all the more interesting). “Others” like The Iron Sheik and Bolsheviks became fictional substitutes for real life international political conflict. And also nothing can be more in the line of the Founding Fathers’ intentions than wet men pinning each other for the right to declare themselves champion.

These men and women performing feats of strength and agility in the ring consumed me. The performers were unreal, otherworldly, impossibly human. They weren’t superheroes but could do things only superheroes seemed capable of accomplishing. They flew. They lifted people over their heads. I don’t know if I was highly invested in the narrative beyond “this person is a bad guy (heel) and this person a good guy (face).” It was the performance itself. In my eyes, it was magic.

Magicians hone their skills. Slights of hand and redirection are practiced to better the illusion of magic. We are not so much amazed by the trick itself but by the fact we are in awe in spite of ourselves. We know Copperfield didn’t make the Statue of Liberty disappear, but we are just as impressed by how he could, for an instant, suspend our disbelief. Wrestling is capable of such postponements. The immense amount of skill is what continues to tie me back to that childhood wonderment and pleasure.

In the past month, a match featuring Ricochet and Will Ospreay from New Japan Pro-Wrestling went viral. The match was criticized by many for not “selling” moves – the fact that both would get punched or kicked or choked, but continue working as if no harm was done (attempting to appear real) – however, most were impressed by both wrestlers’ abilities to fly through the air, twist and turn, and move in synchronized opposition.

It’s stunning and looks more like a Cirque du Soleil show than a backyard brawl. It is full of acrobatics and Olympic-level gymnastics. They might not be “really fighting,” but it doesn’t matter as their ability to weave in and out of moves provides an incredible illusion and narrative of equals jockeying for position.

Count 2: Narrative

Wrestling is a multi-level narrative of stories told with speech and through action. It’s ballet with more sweat, hair, and spandex underpants.

There is melodrama. Male melodrama. Best friends betraying each other for title opportunities. Egos humbled after defeat. Swelling emotions when the underdog finally defeats the giant. Like most soap operas, the narrative can be hackneyed, but at times also self aware and a means to an end.

These narratives are also living, breathing texts. Not metaphorically – a sense that a text remains relevant over a period of time. While wrestling narratives have writers and planned arcs, characters and plot points are rewritten when required. If the audience rejects a character, after so many attempts of trying to push through, the wrestler and writers have to regroup and redirect. If a wrestler gets injured, narratives have to be rewritten in order to accommodate their injury. These rewrites can get particularly complicated if the performer is major character, like recent (former) World Champion Seth Rollins or John Cena (arguably the most successful wrestler of all time), both of whom were out for months with injuries this past year, leaving large gaps in the narrative. Arcs have to be placed on hold, other narratives have to be moved up or redirected to accommodate.

A YouTube video by writer/director Max Landis circulated a couple of years ago about the WWE’s ability to build a character, comparing professional wrestling to Game of Thrones. It is one of the most dynamic “readings” of wrestling narratives and the fact storylines can and have been maintained over decades. Using Triple H, a wrestler whose career has spanned two decades in the WWE and multiple character shifts, Landis dissects the way the character has both shifted over time to remain interesting, but done so in a way that also remains true to the initial character. The video not only acts as a love letter to wrestling but also as a reminder to the amount of labor writers and wrestlers put into the writing. Writing on the fly doesn’t always work out flawlessly, but considering the amount of time provided, the history they’re working in, and the demands from the audience, what they’re able to accomplish shouldn’t be treated flippantly.

There are also, of course, the narratives told in the ring. The wrestling. If you listen to Steve Austin’s podcast, The Steve Austin Show, you’ll hear him talking with wrestlers (both retired and active) about beats, pauses, and full stops. For a match to be interesting, there have to be breaks and moments. Suspense is created between large actions. The audience demands a good story and wrestlers are the stortyellers. It is not rare to hear a stadium full of people chant “BORING” when they are displeased with lack of emotion or high impact moves, or “THIS IS AWESOME” when they approve of the pacing and performance of those constructing the scene. And to fit in with the nature of improvised storytelling, performers make alterations to move the audience from apathy to engagement.

There are times when the WWE can be disappointing or lazy in its storytelling (which is to say, they don’t abide by how I would tell the story) but others when it feels satisfactory, if not perfectly executed. A heel turns at exactly the right moment. A finishing move brings about the picture-perfect denouement. Even at its most frustrating it becomes a source for all of us to collectively complain and figure out ways for it to better.

Count 3: Ideology and Industry

Despite the magic and performance so far discussed, like any art form, wrestling is a commercial industry. It’s popular culture, which means certain baggage comes attached. The WWE, in particular, has never had a completely clean history when it comes to representations of race, class, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, disability . . . pretty much anything problematic has or continues to happen. Let us remember Kamala, the “savage” from Uganda who had a bone through his nose, Billy and Chuck’s #nohomo wedding, and the overall use of women which have traditionally been ornaments for the male gaze with sporadic occasions of legit wrestling talent (often under-utilized to make space for male wrestlers).

Because of the rapid nature of storytelling, wrestling relies on shorthand, which sometimes also betrays a short sidedness. But studying popular culture means I’ve gotten used to liking things I don’t necessarily agree with politically or ideologically. I critique the texts I love. Nothing exists without “flaws” (a matter of taste). Facing such a dilemma also creates a lot of analytical opportunities.

The WWE, for example, has been in the throes of a Divas Revolution, wherein women are gaining status as athletes and performers in their own right as opposed to narrative devices for their male counterparts. Women have no doubt had a place within wrestling’s history. Documentaries like Lipstick and Dynamite, Piss and Vinegar: The First Ladies of Wrestling and GLOW: The Story of the Gorgeous Ladies of Wrestling provide insight into the extent of which women have been participating in this industry. The WWE itself has had a more complicated tradition with waves of talented wrestlers intermingled with models who can also wrestle. This revolution comes at a couple of intersections – the rise in popularity of WWE’s NXT brand, for example, which allowed women to demonstrate their physical prowess and skill in longer technical matches. Women used their time on screen to address their lack of narratives and demanded that more of their matches be aired. The revolution hasn’t been perfect (it’s made-for-TV, after all), but their attempt to address disparity in some way has been something to cling to. And it’s hard not to feel empowered watching wrestlers like Charlotte Flair, Bayley, Sasha Banks, and Becky Lynch consistently dominate in the ring and support each other doing so.

Watching the industry try to keep up with the times and stay removed from controversy has at times been more interesting than the narratives played out in the ring.

If anybody balks at the idea of wrestling’s penchant for melodrama, they ignore the intricate and sometimes tragic narratives of the industry. Retired wrestler, CM Punk claims to have been fired on his wedding day, receiving a “Dear John” letter from the company while dressed in his tuxedo. After settling his contract, he sat for an interview for fellow (non-WWE) wrestler Colt Cabana’s Art of Wrestling podcast, wherein he tore into the industrial practices leaving wrestlers injured and exploited. Hulk Hogan’s life outside of the ring appears more like a Lifetime original movie than life itself: a contentious divorce, gossip surrounding his relationship with his daughter, a sex tape involving himself and his friend’s wife, racial epithets that would lead to the WWE terminating his contract, and a 100 million dollar lawsuit against Gawker. There is also the slew of wrestlers who for various reasons have died before the age of 60 from overdoses, complications from alcoholism, accidents, heart attacks, and suicide.

Submit

Underlying the incredulity concerning my wrestling fandom is a snobbery that associates WWE with children and the working class (those dupes!). My father has heard similar reactions to his love of Nascar, which he considers geometry in motion and practice. We are not indulging in irony, as many seem to assume (“seriously, you like this thing?”). We, as our fellow fans, are earnest. I wouldn’t spend six to ten hours of my week (at least) watching and reading about something I was not genuinely interested in, brainstorm my fantasy entrance (I would parade to Perfume Genius’s “Queen” and take up every second), nor would I have applied to be a writer in 2014, or bought any of the t-shirts – that would be a waste.

I enjoy wrestling as a fan because I respect it as an athletic endeavor, an art, and a performance. As an academic, it offers a host of intricate ideological knots to untangle, which is a different type of pleasure. Wrestling bridges gaps. After incorporating wrestling .gifs in my PowerPoints, some students would approach me to talk wrestling. Former students have contacted me recently confessing they just started watching again – a safe space. I’ve gotten more high fives wearing my Macho Man baseball cap around the city than any band t-shirt or sports logo. Wrestling tends to remind people of those times in front of the television, their brothers’ backyard wrestling, or that terrible movie Hulk Hogan was in (or that great movie and even more relevant film, Roddy Piper starred in). It brings us back to a place where superheroes weren’t so far removed.

Wrestling promises nothing more than play, something we all need and make little room for in our adult lives. Nothing brings me more joy than a heel’s well-placed insult, an unexpected narrative turn (if and when that happens), or a move that even impresses those performing it in the ring. Wrestling is fun and still real to me, dammit.•

Feature image courtesy of Robert McGoldrick via Flickr (Creative Commons). Other images courtesy of John McKeon, Robert McGoldrick, John Jewell, Miguel Discart via Flickr (Creative Commons) and Leandro Gonzales de Leon, MandyJC72, JBZA2003 via Wikimedia Commons (Creative Commons).