My friend Iskra sent me the condo real estate listing on the last morning of my trip to Turks and Caicos a few months ago. I awoke to her texts urging me to buy this and rent it out, and let’s be Golden Girls one day and that we’ll build a fireman’s pole connecting the two units! The spot up for grabs was directly beneath the one she owns and rents out in Crown Heights, Brooklyn.

Right away, I thought it looked pretty great. Not a “true” two-bedroom, but the duplex had a basement that I was sure I could showcase as a second sleeping area. It was modern and cute, albeit ground floor and street-facing but . . . location, location, location! It was in one of my favorite neighborhoods on Franklin Avenue, and having an “in” with Iskra on the condo board meant I knew the building was in good standing, and of course, I knew exactly how much and how easily she rents hers out.

Sitting straight up in bed, I contacted my realtor, the husband of my best friend from childhood. I forwarded the listing to a handful of friends, with the caption — I’m going to buy this — to make it feel real. I sent the same text to my dad, to let the gravity of this decision and his future involvement sink in.

I was going to revenge-buy a condo to get back at my brother.

Purchasing real estate had been on my mind for several years. At 41, with all my financial affairs in good standing, I knew this was what grown-up people like me did. But New York City felt big-time and risky, with such large down payments required. If I were buying anywhere else, I could probably do it on my own, but I wouldn’t be able to buy in this market without the financial assistance of my dad. And that was just the point, this was something I was owed. This, due to the news I got six months earlier, turned this piece of real estate into my birthright.

On a busy Thanksgiving night in a large colonial home-turned-restaurant in Cape Cod, I was with my dad, my new boyfriend and my dad’s relatively new wife. In line to be seated, I casually inquired about my childhood home. The house my dad, brother, real mom and I lived in since I was three years old was sitting idle for several years, uncared for, not on the market but not not on the market. It was a showpiece back in its day, a contractor once told me; the large four-bedroom sat on several acres of land, nestled in the idyllic countryside of Solebury township, Pennsylvania, an hour’s drive north of Philadelphia. But since my mom died five years ago, my dad did what any old widower is wont to do and quickly found a new wife and moved on and in with her a few towns away.

The Solebury house reeked of my mom. My dad even built a shrine to her during the early Covid days of lockdown, cementing the fact that his new wife would never step foot in that place — and she hasn’t once to this day. My childhood home was slowly rotting, undignified, and the shrine and memories of my mom were left to collect dust.

“What’s the latest with the house?” I asked my dad. We were sharing the crowded restaurant entrance hallway with a giant armoire full of nutcrackers.

“Oh, I sold it to Peter!” My dad flashed his white teeth, looking down at me in close range. He smiles like this when he’s nervous.

“What?” I was smiling back, startled. “When?”

“We’re transferring the title soon.” Waiters bumped into us, passing with trays balanced on their shoulders on their way upstairs.

“You’re not trying to sell it to a developer anymore?” This had been the last update I’d been given, that the house was unfit for human habitation. It might have to be torn down, or at least completely gutted, and be sold for much less than market value.

“No, I sold it to Peter.”

“How much?”

My dad grew more somber, looking away as his smile retreated into his mouth.

“How much?” I repeated. I stopped smiling now, too. Then my dad released a number, perhaps a similar amount to what he had paid for the house more than 30 years earlier. It went without saying that our neighbor’s house had sold for four times as much just a few years back.

“It will come off his inheritance. This won’t affect you.”

I held back tears, wanting the conversation to end, ready to perform the silent treatment for the rest of our evening. I seriously contemplated grabbing my boyfriend and driving back to New York City.

Of course, he only revealed this to me when directly confronted, he knew it was not fair, he knew it would make me furious.

The reason this news was so gutting, one of the reasons it made me want to throw an adult tantrum, was that my older brother Peter and I hadn’t spoken since our mother passed away. I tell friends we had a falling out, though I am quick to add, I’m not sure if Peter knows we had a falling out. This makes our situation sound a little silly, because it really is. For Peter to acknowledge we had “a falling out” would be a call to action, something to be discussed, and my brother, like our dad (and like me), is very non-confrontational.

I stood up to my brother for the final time one month before our mom died, in the living room of our childhood home. I was fed up with his bad attitude and ready to cut off all communication — and with our mom’s impending death, comingling would soon become less necessary. Tension from our text exchange the night before was thick and prickly, and I initiated the dialogue as my dad sat in a chair, a little off to the side, with his head hanging in silence.

“When Dad dies, I don’t think I want to talk to you ever again.” I was angry, tears ready to spill down my cheeks. My words were provocative on purpose, a lifetime of feeling like he didn’t give a shit about me made me want to pile on to the vanishing family members.

“When Dad dies, I don’t think I want to talk to you ever again,” he parroted. I was a bit surprised, but also not. Creativity was not Peter’s strong suit.

Peter still lived in our hometown, and, not unlike many of us, he has suffered a series of failed relationships and missed job opportunities. But, he too, was in a solid financial position, he makes excellent money, and living in a small town allowed him to save and save. He owned a condo a few miles down the road. But anytime I ask the smallest favor of him (like picking me up in Brooklyn on his way back from JFK so I could visit my mom — the subject of this final fight), it comes with immense emotional blackmail and conditions.

I am not necessarily proud of my side of the street, or how I approached my arguments, but we were mostly just speaking two different languages. “If you put my address in Google Maps, you will see . . . the time difference is a total of 10 minutes . . . from point A to point B . . . but from point C, it is this time minus the difference. . . . ” I should have known that winning the battle with facts doesn’t always win you the war.

I also wanted him to acknowledge particular details of our interactions over the years, positioning him, I thought, as the antagonist in our life story. Why couldn’t he see he was wrong and I was right — I had logic on my side to prove it! I wanted him to say that he always had it out for me.

Peter didn’t have a list of grievances to unload but repeated that I “take, take, take, and I don’t give” several times. I get what this means but I don’t get what he meant; he wasn’t seeing his actions from the right perspective — my perspective.

Maybe I am pigheaded, like Peter. Perhaps I was missing the bigger picture. We were two hurt children losing their mother, and neither of our lives were in the places we wanted them to be.

My dad added almost nothing during the hours-long tit-for-tat, he just listened as his children, whose mother was in hospice care, lobbed accusations at each other, red-faced and in pain.

After she died, we stuck to our word. We stopped communicating. At first it was gradual since my dad fell off the roof of our house and required assistance for his ongoing prostate cancer and atrial fibrillation treatments. But once our dad settled down with his new wife and new life, we had no reason to cross paths. Peter’s birthday happened to be the day after the fight, which was also my mom’s last birthday (she went into labor with Peter on her birthday) and since I was still in town, the three of us sat down for an icy dinner at a restaurant along the Delaware River, at our dad’s urging. I was still searching my brother’s eyes for some kind of remorse. I found only hostility.

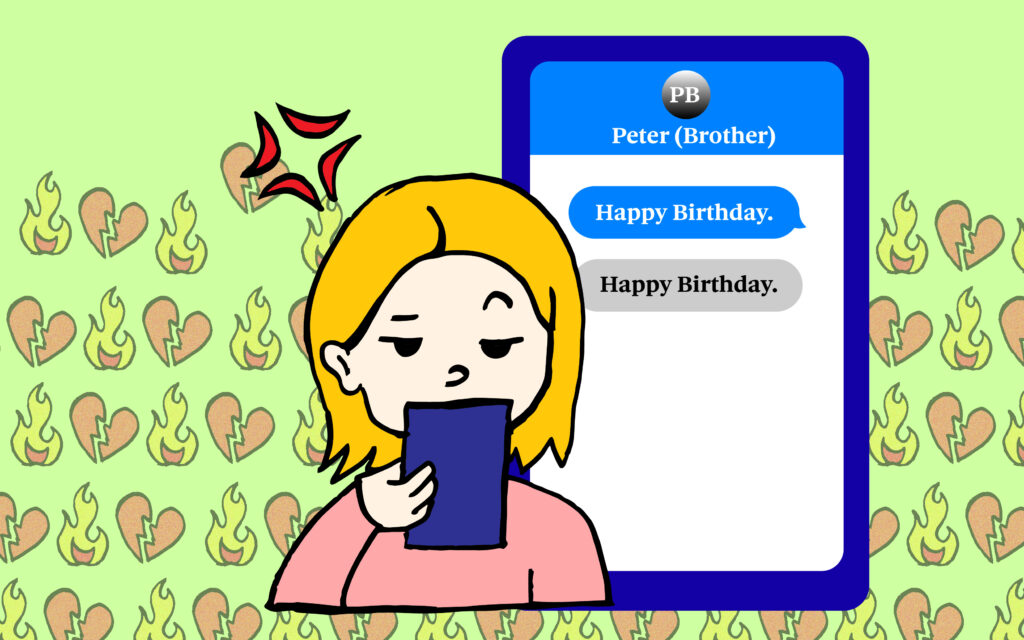

Peter texts me every year, “Happy birthday.” Period included. I text it back to him on his birthday. When I underwent surgery, he texted to say he hoped I was fine, but that is the full extent of our communication over the last few years. Even before my dad remarried in 2021, in a ceremony to which neither of us was invited, we had not seen each other for some time.

My dad spends Christmas with his wife and her daughter’s family now, and for the past three years, I have spent Thanksgiving with my dad and his wife — without Peter, since he conveniently works on that holiday. I might see my dad once, maybe two other times each year. For the Thanksgiving reunion, he usually spends money on a nice Vrbo somewhere, like this last time in Massachusetts, since it’s an area in which they are contemplating relocating out of Pennsylvania. But they don’t seem to be in any big rush.

Neither of my dad’s children is married or has a family to spend the holidays with.

Back at the dinner table in the converted mansion, I was sulking and seething, thinking about my brother having a leg up on me. I managed to corner my boyfriend on his way back from the bathroom to tell him about the conversation with my dad.

“Were you trying to buy that house or something?” he asked, looking nervous about what I might say.

“No, but Peter’s not going to live in it, he’s going to flip it and make money.”

“Are you sad about the house?”

“No. It was always going to be sold someday. Peter just lowballed him, it’s like my dad is giving him much more money, the profit he’s going to make on it when he sells.”

“Did you want to try to make a counteroffer—”

“No! I don’t want the house, that’s not the point. The point is that it’s unfair that Peter gets it for so little. Off his future inheritance, my ass. And why didn’t my dad tell me? He knew it would upset me so much.” We dodged more waiters, without resolution. I relented and returned to the table to get on with the night.

Then it suddenly occurred to me to get something out of this — this was an opportunity, I realized. I confronted my dad at the table — I didn’t ask but told him — “You’re going to give me the same amount of money to buy a house. Off my future inheritance.”

“Of course,” he said, very quickly, reassuringly, happy to have some kind of closure on this. He’s a very generous man, but he is careful to make things appear even with his children. He doesn’t want to give the impression that he’s taking sides.

He never asks me about Peter, he never asks about us reconciling. That he can’t do. But he can give us money.

I was in Turks and Caicos because I have a friend who works for a charter airline, and she told me last-minute that I could travel to the resort with her for free. She put on her flight attendant outfit and wheeled her suitcases out of our bungalow earlier that morning, and I was figuring out what to do with my final few hours when I saw the message about the condo.

After a few giddy minutes of sending texts, my head was swirling with thoughts of owning my own apartment and getting some well-deserved revenge. I’d use my dad’s money to make the down payment, I’d get amazing renters, they’d pay my mortgage . . . but what is a mortgage? What are interest rates? How does that work? And how much is the optimal leverage amount for tax deductions on rental income? That last question was not mine but came later from a CPA.

I decided to do a mangrove kayaking tour before making my way to the airport and back to New York to set my plan into action.

Surrounding my mom, who was reclining on her hospital bed the morning we learned about her glioblastoma diagnosis, my dad, Peter and I spoke with the attending physician. Peter didn’t seem to grasp the meaning of a malignant brain tumor fully, I thought. He knew it was bad, but when my dad and I locked eyes, I could tell he got it, that only he was in the same terror-stricken place I was. Most people think cancer is a thing to be fought, like a battle where one can become victorious. Fuck cancer. Well, not glioblastoma. I read the night before (after taking my mom to the emergency room due to her stutter and subsequent bad MRI) that her odds would be almost zero at her age to survive two years past diagnosis if the results came back positive for the disease. My dad and I continued to shoot each other silent eyeball screams as the doctor answered our questions. What size was the tumor? A golf ball, but with the swelling, a baseball.

Fear strangled me. I was too immature, too ill-equipped to be left with these men as my remaining family — to lose my mother. Peter and I had been trying to get to a better place in our friendship for several years but the new reality of caretaking, doctor’s visits and dealing with dad’s erratic emotions would be a bit too much for us to bear.

When my brother and father left to find snacks and I was alone with my mom in her hospital room, she finally said something.

“I guess I won’t live to see any of my grandchildren.”

None of us believed in an afterlife by then.

Two and a half years later, and a month after my brother and my big fight, a doctor doing his rounds in a hospice home, stumbled upon a scene of a broken family of two adult children and a withered old man, sitting but not talking around my mother’s deathbed. My mom was nonverbal, too, and couldn’t walk, and she was beginning to struggle to breathe. The doctor said that her death should be dignified, implying we all looked so undignified. He brought in a nurse to administer the fatal morphine dose that would stop her breathing and end this chapter of our lives.

I am now under contract to buy the condo, but somehow, I still won’t officially “close” for another month. I think I have that right. It was a pretty fast process of offering, then counter-offering even more to beat out the next prospective homeowner to get my offer accepted. My dad and I have had some tense conversations during this time, it did not go down so easily. I felt belittled and small, like a little girl who knew nothing. But forking over the cash to his ill-prepared daughter for some kind of investment property, which I think he knows comes from a place of spite, is probably difficult to watch unfold.

The excitement I felt in Turks has waned. There are scary, uncertain things involved with homeownership — condos, in particular, it turns out. And soon I will have tenants, like children, who will have their own questions and need help from their master overseer, their lady of the land. I will be their landlady.

There are scary, uncertain things involved with growing older when you’re looking for meaning in things you cannot have, things that aren’t real, things that are gone.

Friends who know me from childhood — and my brother as the older classmate who you didn’t want to piss off — ask how things are between us sometimes. I explain that this is the best relationship we’ve ever had — this one, now, the one where we don’t talk. We’re in a good place, I say. They laugh and move on to other subjects.

Perhaps we will reconcile one day, but we’ll never be close. When our dad does die, we won’t lean on each other, we’ll mostly be alone to figure out this final chapter in becoming orphans. But we’re going to get a fat lump sum of inheritance to do with what we please.

Peter might be in over his head with home renovations and could lose money in the end, I think, though I doubt it. I’m sure he’ll learn a lot at least.

If I can’t grow up and be happy, at least the condo is something I can control. I wonder if Peter will casually ask my dad about me sometime soon and will learn that I too am acquiring real estate off our father’s back. If I know my brother well, he will be angry. He will think it’s not fair. And somewhere out there I will be satisfied.•