Growing up in the ’50s and ’60s in the South, I was introduced to Jim Crow at an early age. I didn’t understand too much, but I knew that “he” was the law, and that we had to obey the law. Things were very unfair for colored people, and the law made the unfairness legal.

I was unaware of much that was going on outside the confines of my limited surroundings. We lived in the small town of West Memphis, Arkansas, a rural community minutes from downtown Memphis, Tennessee. Grownups never talked about the Freedom Riders, the March on Washington, or the 16th Street Church bombing in front of us children. With only one television in the household, it was easy for them to monitor the information we received.

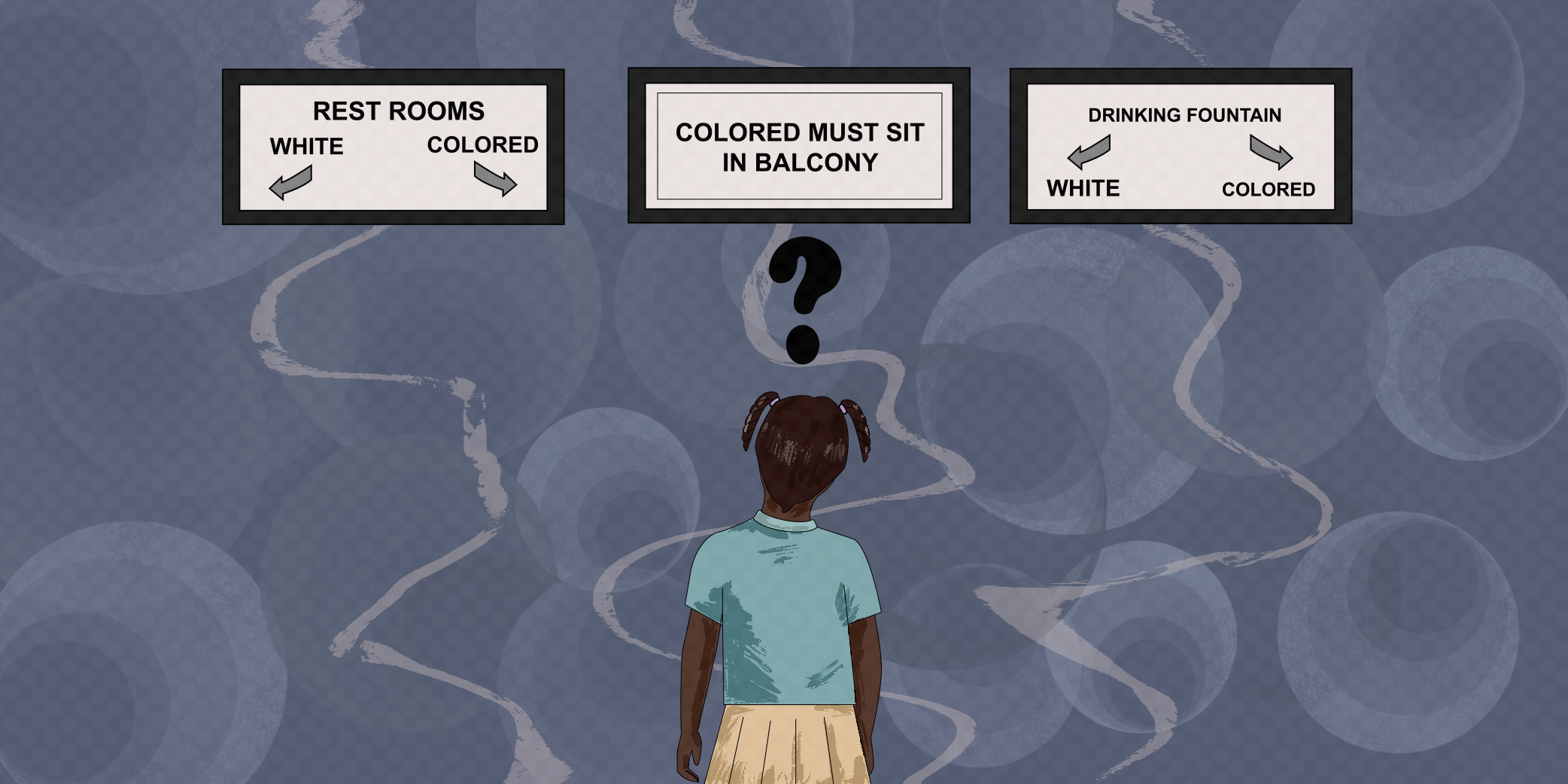

They tried to shield us from the horrors of racism, but racism was everywhere, especially in the South. When racism reared its ugly head, it would not be ignored. I could not ignore the signs: “whites only,” “help wanted, no colored people needed,” “colored entrance around back” or “colored people wait outside.” I always wondered why? What had we done to deserve this?

Although I was very young, I knew something was wrong with how we were treated, and something needed to change. We were taught to fear white people in order to avoid trouble. Occasionally, I would hear the whispers of adults talking about a young Black boy being beaten, lynched, or castrated. When that happened, there was a sadness that engulfed the community, and nothing the adults said could penetrate the sadness or lessen the fear. As I recall, nobody even tried. They just let time heal their hurts until another episode occurred. In the meantime, it was back to normal.

Normal for us who were Black was not what I considered normal. My older siblings had to go to the back and up to the balcony at the movies. We were prohibited from certain stores and restaurants, and even certain neighborhoods. When we went door to door selling Girl Scout cookies, we knew where not to go. On the rare occasions that we went out to Hamilton’s clinic or shopping, we had to go to the “colored” bathrooms and water fountains, and they were both always unclean. I always longed to taste the water from the white fountain. Imagine my surprise when I finally did. It was the same water!

Another blatant insult to us was not being able to sit down at the lunch counters. Sometimes we had the pleasure of going to downtown Memphis to shop. I was always mesmerized seeing the statues around the courthouse. Sometimes we heard music coming from the park. The tall buildings, which really weren’t tall at all, made me think I was in New York City or maybe even Heaven. The icing on the cake was having those delicious hot dogs at Woolworths. They were huge, roasted on a rolling grill, and served on a toasted bun with an array of condiments that I only saw there. We didn’t get out much, so I cherished my rare fantasy until reality interrupted. We had to get our food to go. Even though no one was sitting at the tables or counter, we couldn’t. We had to stand up and eat over on the side designated “colored.” I knew my parents were tired of explaining why. Their only answer was “that’s just the way it is. Maybe one-day things will change.”

When the movement moved to Memphis, I finally had hope. I knew that these people were marching for change! April 2, 1968, as I remember it, was an especially gloomy and ominous day, echoing the overall mood for black people in America. There was a boycott on the horizon, and no one knew what was going to happen.

Everyone was talking about the march downtown. Supporters were to impose sanctions on local businesses by not shopping. But we were headed downtown this particular day . . . to shop. Unbelievable! My heaven was now my hell. Mom had asked Daddy not to go. But Easter was coming, Daddy had gotten a bonus, and we needed new shoes. Besides, no one could tell Daddy what to do. He was a pastor, for God’s sake. His solution was to go early, before the march. I was disappointed in my parents, but it was the era when children were seen and not heard.

Nothing was the same that morning. Downtown was like a ghost town. No people, no music, no hot dogs, no joy. We made our selections, hurriedly, and started to leave. As we turned the corner, there they were. The marchers. They covered the street from one side to the other and there was no definitive end in sight. I never knew that many people existed, all arm in arm shouting “Don’t Shop, Boycott, Don’t Shop, Boycott.”

There were about five other people shopping. The protestors were destroying the shopper’s belongings and roughing up some of them. They were angry. Years of oppression had finally culminated into this one moment in time. I could see it in their eyes. They meant business. As we stood there frozen, I saw something in my daddy’s eyes that I had never seen before, fear. I was afraid too, but pride outweighed my fear. Black people were standing together on one accord for change.

As we stood there not sure of what to do, one of the leaders ran up to us. It was Jesse Jackson, Julian Bond, or maybe even, John Lewis. I don’t know. I do know that he was just the tallest man on earth! He asked Daddy, “Sir, why are you shopping?”

Daddy replied, “we don’t live around here; we didn’t know nothing about the march, and we don’t know nothing about the movement”.

Liar! Liar! I wanted to scream. I think the gentleman knew he was being lied to, but his compassion for this older man and four little children outweighed whatever negative emotion he was feeling. I think he sensed that Daddy was embarrassed, as well. So, he responded with kindness.

He asked, “Sir, aren’t you tired of being treated like a second-class citizen?”

“Yes, Sir,” Daddy replied.

“Aren’t you tired of being discriminated against day in and day out?” he continued.

“Yes, Sir”, Daddy replied.

“And aren’t you tired of not being treated like a man?”

Again, Daddy replied, “Yes, Sir”.

“But most of all, sir, aren’t you tired of telling these four little children that they cannot go where they want to go, sit where they want to sit, be what they want to be, or accomplish their dreams because of the color of their skin?”

“Yes, sir,” Daddy answered.

Our hero replied, “that, Sir, is why we are marching today. That is what the movement is all about.”

He had Daddy put the packages under his coat and walked us to our car. As he walked away, he told us to be safe. Daddy waved and shouted, “thank you.” Although we appeared to be on opposite sides that morning, I realized that we are, in fact, our brother’s keeper. I marveled at the simple concept of unity. I have never been so proud as I was that day. I saw strength, perseverance, dignity, and compassion personified. To me that was what the movement was all about. Umoja!

That night, Martin Luther King delivered his famous “I Have Been to the Mountaintop” speech. I had been to the mountain top that morning. Nothing was the same after that. From that day on, when we gathered around the TV, Daddy included the news. As a family, we watched coverage of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and we all cried together.

Although we were crushed, in my heart, I knew that the movement was bigger than one man. Martin Luther King Jr. was just the beginning, and as he said, “we may not all get there together, but together we will all get there.” I had the answer, each one, teach one. Racism hurts everyone. I wondered what would happen if we all looked out for each other, as the tall man had looked out for us earlier. Maybe, just maybe, we would not celebrate occasional victories but eradicate racism forever. •