March, 2020

I want to put it all down before I forget. Before all of this becomes normal. It’s already becoming a little bit normal; the start of some new era. And right now, a month in we can’t tell if this is just the beginning of a time that will be over soon. Or something deeper, darker and more permanent. A pit being dug that will swallow us all up.

The world has changed but my view of it has not in about 30 days. Spring is filling in my backyard gradually like an imperceptibly sped up time-lapse film I’m watching where it feels like 24 hours equals about 23. New details come into focus gradually like in an impressionist painting. Flowers grow a little more into their own each day, the grass gets less yellow and the buds open up on the branches like a slow-motion yawn. Or scream. Time seems to crawl here in my little home office but out there in the world, dark events roll past quickly like storm clouds.

•

The maps of the virus show New York City covered by a bright red throbbing sore. My town upstate is outside of that area, for now. Its case numbers a healthier rosy pink color. Before all this I would commute every working day by train and then walk a few blocks to my job from Grand Central Station among the throngs of people who were always moving a bit too slowly or too quickly, forcing me to constantly adjust my stride. All of that has very suddenly become part of a past, which is now disproportionately distant — like looking through the wrong end of a telescope.

I’m reminded of those old Twilight Zone episodes where a character suddenly finds themselves in an unfamiliar world. Either all the people have disappeared, transformed, or there are aliens. In nearly every case the character’s first reaction is denial and then hope that they are in a dream from which they’ll soon awake. References to the end of the world now register at a higher frequency and grab my attention the way a high-pitched whistle will make a dog’s ears prick up. Watching a Buffy the Vampire Slayer rerun, I heard Buffy say, “what if there’s a pandemic loose and we’re too late to stop it?” That got my attention. As does every scene involving people in crowded places. They now look either irresponsibly reckless or blissfully unaware of what’s to come.

•

My life has now become a miniature version of the one I had before. Or, maybe more accurately, a thin slice of my previous life, the one containing my hours at home with the other layers cut away. If I go outside, I glimpse the borders of those other layers — the train tracks leading towards the city, the empty tables inside restaurants, or the out-of-state license plates on cars that pass.

Since this all began, I’ve noticed my dreams have started to incorporate visits from nearly everybody I’ve ever known; as if I’ve needed to check in with them to make sure they’re ok. In real life, paralyzed by the enormity of this event I’ve only been in contact with a few people. Mostly it’s just been my wife and me, daily calls to our mothers, and the occasional group chats on video platforms that make it look like we’re guests on a low-budget news show.

•

The NBA announces it’s suspending play. It happens shortly after a player makes an ill-conceived joke at a press conference about spreading the virus then later tests positive and apologizes profusely. Somehow this is an inflection point that convinces me of the enormity of this crisis. I have marked the seasons with the opening and closing of sporting leagues my whole life. In the absence of live sports, reruns of old games appear. They become a time machine reminding me of where I was at those moments. In a crowded London pub with my sister as David Beckham scores a last-minute free kick against Greece, the two of us secretly disappointed for our Greek compatriots amid the mayhem. Past my bedtime in front of our suburban TV when Muhammad Ali lost the crown to a cocky young Leon Spinks. Alone in a New Orleans bar watching my Montreal Canadiens win a Stanley Cup feeling jubilant but homesick.

When the lockdown was announced it was as if we were all playing a huge game of musical chairs and the music has not yet restarted. All my previous life decisions leading up to this point now feel more permanent and unalterable. Like my decision to buy this house my wife and I live in that has now become equal parts refuge and prison. I’m grateful for the isolation it affords. That same isolation was the very thing that gnawed at me when the world was the way it was before. The density of the city and its unpredictable interactions — things I missed after having lived in Brooklyn for the past decade — are now killing people and driving them inside.

The sharp outlines of my fate lead me to revisit all the choices I’ve made that have taken me to this moment. But I’m also at the mercy of all the choices of others swirling around me that have swept me up into this predicament. Which is life, I suppose. And history. I think about my decision to emigrate to the US and my complicated feelings about my adopted home. I’m ambivalent about this country at the best of times and these last four years certainly haven’t endeared me to it anymore. The national tendency toward blind optimism without any concrete action now seems directly responsible for a growing tally of deaths. My Twitter account is an endless scroll of outraged finger pointing at official incompetence and venality intertwined with stories of anonymous suffering and heroic sacrifice.

•

Rooted in place I let my mind wander.

Every morning I wake up and the daydreams of places and things I long for engage in a simmering rivalry with the unblinking realities before me. My frozen circumstances are a now living balance sheet of all my good and bad choices. What led me here in a literal sense was an ad for the American Green Card lottery brought to my attention by my father. My initial reaction was indifference or even self-righteous hostility. Why would I want to move to the US? Its crassness, hypercapitalism, and rabid individualism all conflict with my values and nature — my Canadianness. But my father saw an opportunity for my future so I entered the life sweepstakes and a little while later I was informed that my name had been chosen. “You’re so lucky!”, everybody told me. I wasn’t so sure. But the Quebec economy was sinking and I was drifting into oblivion of torpor and unemployment insurance checks so I tried my luck. First in New Orleans, that beautiful disaster of a city.

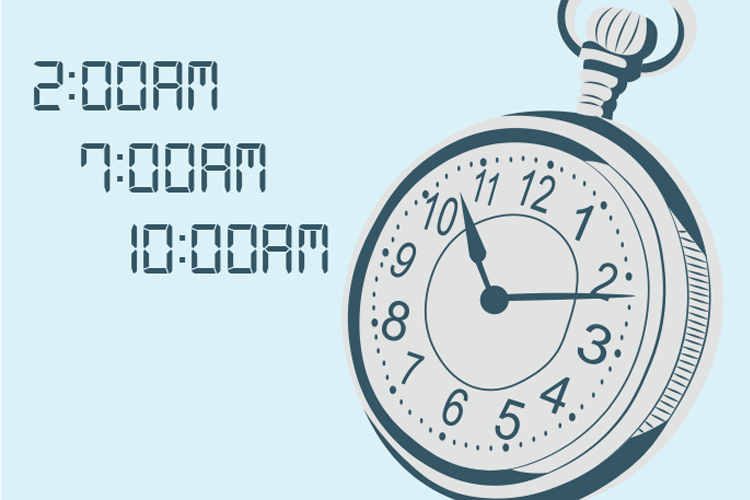

In my wanderings across the fertile tangled landscape of the internet, I come across an article about my former home from 1996 by Andrei Codrescu, the city’s unofficial chronicler and poet in residence describing it as a place that “emanates an intoxicating scent of decay and promise.” I perk up when he mentions Coop’s Place, the restaurant I worked at for a year as a dishwasher and waiter. I remember the day I served him, and now reading his descriptions I’m plunged back into my memories of the place more vividly. He describes a kind of lazy, unashamed decadence. I remember working until two a.m. then drinking until six or seven in the morning since the bars never close. Sometimes when I showed up for my shift at ten a.m. the cook who had worked the night before would still be on the street outside in the middle of a 24-hour bender, uncharacteristically cheerful. This was all considered normal for New Orleans. As was the murder rate, which topped the nation. The bar next door kept a running tally in its front window comparing it to Boston’s, a city of comparable size with a murder rate about a tenth as high. Everybody I knew had been a victim of a crime, including me at the hands of three kids with a gun, who looked they were still in grade school. The people in places like New Orleans who shrugged at the murder rate now seem equally unconcerned by the virus they were told was a hoax or will disappear soon.

Today, a Tuesday (I think), is a workday so I treat it as such and act as if I were going to the office in an attempt to preserve a sense of normality and maintain the shapes of the days — a bit like a kid playing house or an actor doing an extended bit of improv. I wear pretty much the same outfits I would wear to my office minus the shoes. My commute now consists of a walk down the stairs to the kitchen then back upstairs. I open the blinds of my home office and see my backyard and the backyards of my neighbors, and the sky, and I wait. I work, read the news, get diverted by the Internet, or learn Italian on Duolingo. And the day passes like that almost imperceptibly. I have lunch with my wife. Having lunch at home on a weekday reminds me of being a kid home from Greendale Elementary eating while watching the Flintstones or Mary Tyler Moore on the small portable Quasar we kept on the kitchen counter. It’s all very comfortable and cozy until I read the news and feel as if I’m surrounded by a ring of fire.

But here in our Victorian two-story house, we’re protected. I don’t go out except for the occasional walk or drive where life in my little town looks mostly the same except, like in that old song by Morrissey, “Every day is like Sunday.” The restaurants and shops are quiet and they’ve taken the basketball hoops down and put police tape around the playground. In the evening I go down rabbit holes on YouTube or Reddit or stream movies and TV shows. CNN feels like it’s part of a B-movie about contagion — until they show the faces of real doctors and nurses who look shell-shocked and talk about the numbers of dead that keep going up or that they are running out of places to bury the bodies. In that way, it feels like war.

•

On our last trip to the local Stop & Shop, ominous signs appear. The aisles for the toilet paper and bottled water are nearly empty and the checkout lines are suspiciously long for a weekday. To help me cope I shop for groceries online filling a virtual grocery basket . . . Olive oil, couscous, tangerines, cheese, and bread and frozen fish and cans of beets and corn and beans and cans of coke (cheaper by the dozen) like I’m building a towering barrier of produce to keep out danger. In the basement, we store the overflow of cans and boxes of pasta on a shelf guarded over by a small plastic skeleton my wife bought to teach kids art that sits on top of a can of creamed corn like a casual memento mori. But the deliveries themselves are a threat now, too, and have to be treated as if they are contaminated like nuclear waste. We dutifully wipe down each item as we take it out of the bag with the Purell wipes we have stockpiled, wondering how much time to spend on each one. Toilet paper appears and then disappears in my Amazon order basket repeatedly as I imagine millions of other people anxiously typing at their keyboards. Finally, I find a no-name brand from China. When it arrives a few weeks later it is about a third the size of regular toilet paper like some kind of a practical joke.

•

I discover a coronavirus podcast called Coronavirus 411. In a robotic voice, it records the growing number of daily cases, country by country, state by state. It gives me a mini-panic attack, making tangible and quantifiable the sense of dread enveloping my house as if we are hearing a progress report of impending doom. After a few days of this, I stop listening.

•

About a month ago I was dogsitting at a friend’s house, and taking advantage of her HBO membership, I watched the entire Chernobyl series, a drama about the nuclear disaster that stays close to the facts and the horror. In a way, it prepped me for the escalating scale of bad news that characterizes a worst-case scenario. The equation diagrammed by experts soon starts becoming a dark reality; “if this happens then that consequence will inevitably follow,” the scientists explain to doubting officials, as hastily constructed safeguards fall away like a high-rise collapsing under its own weight. Official spokespeople tell the public a more palatable version of the truth, which is soon undermined by reports from the field.

The series showed that sometimes the worst outcome comes to pass despite the human capacity for denial and self-delusion and the best intentions of those who can see the consequences in advance. 9/11 felt like that too. I heard the first reports of a plane crashing into a building on a cab driver’s radio as my girlfriend and I returned from a long train trip in Northern Quebec. I had the same chest-tightening feeling of dread then that has seized me in its vice-grip at times these last few weeks. A ‘how bad will this get?’ sense of vertigo. Now that the parameters of the disaster are being defined more clearly a sort of acceptance has set in. As if we had our Pearl Harbor and we’ve dug in for a long fight ahead. Or maybe more aptly, the Crash of ‘29 has happened and the Great Depression looms.

•

When the quarantine starts, I decide to keep a diary, reasoning that I am living through a historic event that should be recorded. Writing has always been my defense against the chaotic inarticulate ramblings of life. I squeeze the enormity of the world into the margins of a page making them feel manageable.

I always want to write more than I do. Calamities, especially make me wish I had spent more time honing my skills. When my beloved cat Ophelia died, I ached to be able to articulate who she was to me to the world. Since my father passed, I still haven’t been able to find the right words in the proper order to write the epitaph he deserves.

Every day I wake up and I do a little writing while still bleary-eyed but never quite enough. And that’s usually the last thing I think before I fall asleep. But somewhere between the early morning ambition and late-night regret I get sidetracked, turned around the way I do when I’m visiting a new city, and inevitably make a left instead of a right on my way somewhere. Writing is exceptionally lonely. Or maybe it just puts your loneliness into sharp relief. Accessing the thoughts that inhabit your own inner landscape means leaving this world for a little while and traveling through an uncomfortably small crawl space barely big enough for one.

That’s what makes distractions so appealing. And now with all of us struggling to escape the specter of a thing almost as big as the world, the appeal of avoidance and its many flavors is inescapable. Sites like Reddit or Twitter are irresistible stews of nonsense, cleverness, cuteness, and outrage with a bit of information sprinkled in like a valuable spice.

Each day I write a schedule of what I plan to accomplish that includes writing. What I don’t get done gets slid into the nebulous future. It usually starts well enough but sometime in the afternoon after lunch, my body, drowsy and sated, starts to lose the fight, my grip on the day loosening as time accelerates towards the finish line. The minutes form hours and fall into a sinkhole and I curse my inaction. After dinner the pull of passive entertainment via my TV or laptop is strong and my body starts taking on weighty sleepiness like a bag filling with sand.

Working in the garden my hands pulling out deeply rooted weeds I get a revelation that is both obvious and inescapable. All good writing is the ability to tell a truth (or maybe all good writing is is the ability to tell the truth). Maybe the extent one can stand to tell a truth in a personal, unyielding way determines how effective a piece of writing is. I’m not sure I’ve ever been comfortable fully confronting the truth and the effect telling these truths would have on me or anyone reading my writing. Some of the things I think about in the course of the day, I don’t want to share with anybody. I hold them too closely and preciously, maybe because my biggest fear in revealing them isn’t that readers would be scandalized, it’s that they would just shrug. And the last thing I want is for my closely guarded inner reality to be tossed in a pile with millions of others once I give up ownership of it. Articulating these things too acutely or explicitly will give them a life outside my own head — a permanence and a power from which there’s no turning back.

I’m amazed at how little it takes to satisfy me some days. The comfortable thrill of a safe home, a warm cup of coffee, a compelling story and companionship can feel like a jackpot. On other days the list of things I lack or long for never seems to end. These two selves live uneasily within me, next to one another, finishing each other’s thoughts or contradicting one another like loving siblings.

April, 2020

I think of my abandoned office, which I haven’t seen in over a month with its angled view of the United Nations building from the 9th floor. And for some reason, I focus on the plants now left there to fend for themselves. The ones I so diligently took care to water and fertilize and expose to the right amount of sunlight. I imagine them now a month later covered in a layer of dust, their leaves shriveled and brown, gradually deprived of life; the smallest of tragedies nested nearly invisibly within this bigger calamity. A cartoon in the New Yorker shows an abandoned office plant marking the days on the wall with a piece of chalk, like a person in solitary confinement. I think of them and of the day I’ll return to my office to breathe its stale air and put in context the void that has been carved out of all of our lives.

•

On one of our walks, my wife and I see a mockingbird fluttering between the trees and the electrical wires, going through its enormous repertoire of songs as if it was auditioning for us. My wife films it on her phone while I record the future memory. Later as we walk home arm in arm, she explains that the older a mocking bird is the more songs it knows, expanding its playlist with experience.

As I lay in bed reading through the news feed on my phone my wife joins me to see me off to sleep as if I’m going off on a trip (which I sort of am). “Oh no!” I see the news that John Prine has died from complications of Covid.

“You knew him?” she asks.

“Yeah, he was really great,” I tell her and try to explain why. “He wrote beautiful simple songs.”

My spontaneous mini-epitaph is obviously insufficient.

As I read the obituary and learn new things about the man, she asks, “is there music?” After a minute I clicked the link to “Paradise” and we listened to his earthy tribute to his childhood and the place he grew up in. Before it was over, she had fallen asleep on my chest, her body swelling and deflating quietly with every breath.•