Gina Nutt’s Night Rooms is a book of passages. I mean this literally in its form, a collection of nonfiction narrative poems that construct the book, and also metaphorically as each paragraph moves us from one sensation to another, unlocking a series of memories and feelings. Covering Nutt’s childhood, early adolescence, and adulthood, the collection as a whole amplifies the interconnectedness of things: how the horror films we watched in our teens can be foundational for how we process the word, the pleasures, and frustrations associated with the mall’s offerings and potentials mimicking the storehouse of memories housed in our brains and bodies, and how we process traumas built upon the foundations of previous traumas.

Nutt was gracious enough to carve time out to talk about Night Rooms, published by Two Dollar Radio in March. The interview has been edited for time and clarity.

Melinda Lewis: I have a lot of questions, but I want to first talk about [the store] Afterthoughts. I know you reference the mall boutique early on in the book and it’s not like I stopped reading there, but really the memory of sifting through Afterthoughts stopped me in my tracks. It stayed with me throughout the book as an example of what I loved about your writing. Out of all the 90s mall store, what was it about Afterthoughts that brought you to include it specifically in the book?

Gina Nutt: Well, you know, I feel, in some ways, like a lot of the book has that sense of sifting. For some reason, Afterthoughts is the store where I have, like, a really strong smell connection. I can smell it. I can smell the plastic, the ear care solution, the lip glosses, and the body glitter. I can do a whole 90s makeup tutorial. Do you remember the earrings cards? The ones with the gemstones or maybe turtles, peace signs, or smiley faces? I have a strong connection, but it also really fit with the buffet of imagery that is offered throughout the book: images from movies, instances of my life.

ML: I think that’s what struck me so viscerally when I got to this one detail in a section of an essay about malls. You describe malls as a “collision of opportunities,” which, to me, is like being a teen girl — a collision of opportunities, but not knowing what the fuck to do with them. Claire’s seems to be the most recognizable of that type of store, but using Afterthoughts felt more like a secret.

You operate in this inbetween-ess, where you describe [popular] films or texts and I know exactly what you’re talking about, but you’re also rarely explicitly saying what you’re talking about. So much of this book feels like the passing of notes back and forth in middle school. You write in between the lines in such a way that I know you what you’re referring to, but if anybody else, like a teacher, picked up our notes, it would be indiscernible. It felt like we were building something together, but that you were taking the lead.

GN: I love that. I haven’t heard it put like that.

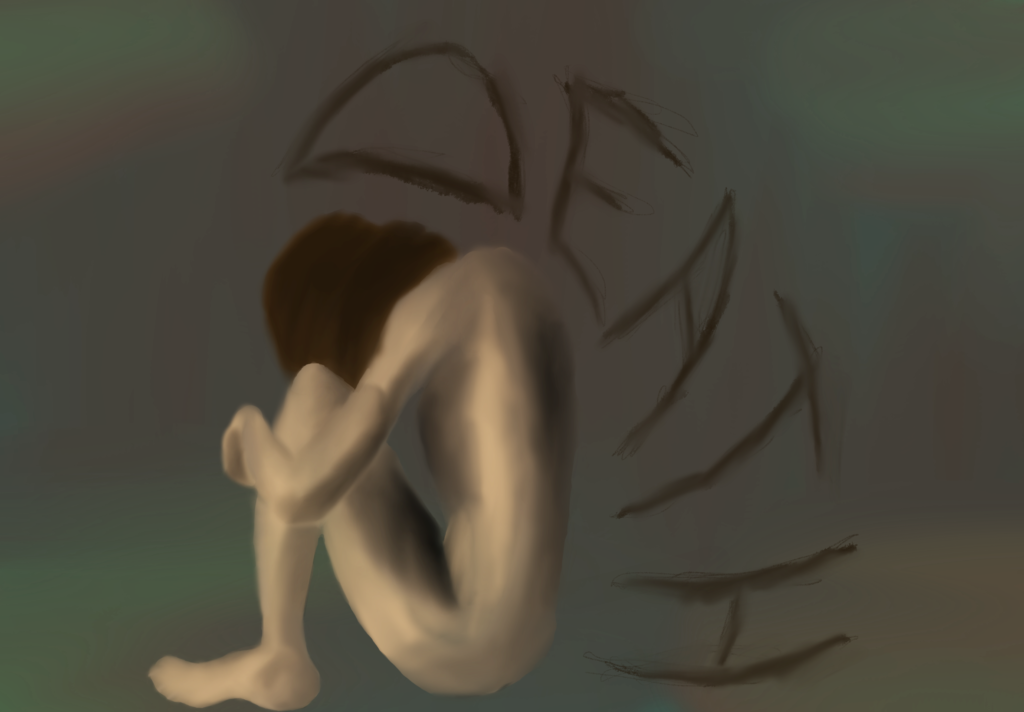

That idea of intimacy, I think, is what the sense that you get from like the passed notes and also, like secrets, which is interesting when you think about some of the things I’m writing about, which are stigmatized. Things that maybe historically were really difficult to talk about and I think remain really difficult to talk about. By building off that I found a way to talk about things that are challenging but also to feel a sense of safety and to feel like I had soft landing.

ML: I would like to stick with that sense of inbetween-ness and operating between implicit and explicit. I don’t necessarily want to say play, because there’s a lot of trauma throughout the book, but how do you negotiate the explicit and implicit when writing these essays?

GN: What’s interesting is like I feel like horror does this too, in a sense. It plays. You have like a really gory kill, or you have the lighting cast a certain way or this music playing a certain way to conjure a certain feeling, so I drew from that a lot. How does that art I riffed off handle trauma? I also think I gave myself permission and asked how I would like myself to handle these experiences. When I was initially drafting, I did write explicitly about those experiences and then when it came to revising, I asked myself, “Okay, what are you okay with? What do you want to have here in this realm?”

It’s a creative choice as much as a personal one. It’s hard, in my opinion, to divorce the two when you write about yourself. So, trying it out and writing a draft that’s very explicit I know that my threshold is there. Then, I can decide where I want to pull back and lean into those more implied moments.

ML: How does your background in poetry integrate its way into this more narrative prose?

GN: I think the lyrical and, you know, thinking of the lyrical moment that might inspire a poem guides me a lot. When I was writing this book, I was thinking “Okay, you’re writing one prose poem after the other.” I was becoming less daunted in a sense by doing this. I think a lot about acoustics, so a lot of the musical rhythms come out. Especially if you enjoy reading aloud. I think there are passages where it’s clear that you could read this aloud and really find joy and pleasure in the lyric.

ML: I think that there’s also the care and consideration of language that just comes through — the joy of how words can create feeling. And, yes, there’s pleasure in the lyrical but also just like some of the sentences are punches right to the solar plexus. And I feel that most often when I read essays by poets, like when I read a piece by Anne Boyer or Elisa Gabbert. It’s not like writers don’t like or think about words, but I feel like the care poets have with language comes through more often.

GN: In learning to write poetry, you learn how to streamline. And I think that’s where those solar plexus punching sentences come from. That aphoristic writing is something that I’m really drawn to in reading and seeps into my writing and reading so it makes sense that it seeps into my own writing. I think of Sarah Manguso’s 300 Arguments. It’s a book that whenever I feel stuck on a piece of writing, I go to that — just open it and go “I’m ok now. I need to get back to work.” It’s creative lifeblood in book form.

ML: I want to go back to this idea of soft landing like feeling like wherever we’re going emotionally within this narrative that there is a sense of commiseration and that, we are powering this through together we are both going to do this soft landing, while also going through, there’s no other way for me to put it, a boggy shit storm.

GN: But I think too like language and sentences, like, those can be a driving force. If it’s going to be dark, if it’s going to be heavy, then you’ve got to give the reader some reason to stay with you, and it can’t just be like this is really sad please listen to me.

It’s about the language. It’s not about “How can I make my pain beautiful?” because I think that’s really hard, and I don’t really buy that narrative. It suggests that everything happens for a reason, when really, it’s just that sometimes horrible things just happen.

But I do I find peace or a sense of like calm in coming to those sentences and giving my character, the language. But there are moments where I do surprise myself, and that might be an opportunity for a reader to feel that. When I know exactly where I’m going to go, I’m never happy. If you know that I know what I’m writing about that’s equally not fun for me or for a reader.

ML: Mostly because it’s not just a list of events. It is a list that continually builds off of each other. It brings me back into your use of like popular culture texts. There is a lot of horror and you bring in some true crime, like JonBenet Ramsey. And as somebody who teaches popular culture and film, I’ve often used these texts as a means of processing information or ideas. I’m really compelled by the interweaving of these popular culture texts with your own work processing yourself and your experiences. How did you start? What are the threads? What are the needles?

GN: I had seen It Follows and a year after that my father-in-law had passed, and I was just it was the first time I was having a hard time writing. I’m someone who’s in my office every morning and it was just a difficult time for me, and I was really stalling out. So, I was like, I’m going to write about death because that’s what I’m thinking about.

I wrote about my earliest interactions with death and how I remember death, including bringing my mother a dead mouse, which made it into the first essay. And it really segued into these anxieties and suicide following me and It Follows, which like everybody else, I love that movie and it still hasn’t left me.

And I kept write about movies and thinking about them, because I knew there were other movies that had an impact on me like Return to Oz and Milo and Otis — these childhood movies that stuck with me and does something to your sense of danger, that at least shaped my understanding of danger and what’s frightening. In the case of Return to Oz, what can happen to little girls who share their dreams or experiences.

Other essays came easier, like Rosemary’s Baby and Suspiria, because I’ve heard lots of conversations about babies since I can remember, and I danced ballet, so my body being the focus, the tool of value that for women, never stops being the case.

At a certain point, I made color-coded note cards where I had movies and themes and taped them on the wall so I could move the pieces around. I was able to weave when I saw it laid out. One thing would unlock the other — I’d bring up this movie, then say “Well, this experience brings up another movie,” and that would unlock another experience. Once I started, it just, like, a domino effect. For a year, I had the cards and up and was just moving them. Back and forth every morning. A cat knocked a piece off the wall that meant like that piece had to go back wherever I thought it belonged. A year of my writing, but it worked. I had faith that it would reveal itself to me if I was patient.

ML: Despite there being so much movement between what you used, yet it reads with such an ongoing flow. It reads more in a sense that you had the puzzle and carved it as opposed to you were putting the puzzle together. One of the ways, we or I, use popular culture is to not only process anxieties but also use as a distraction. Did that come into your decision-making process, that you were relying too heavily on the film portions to mediate the experience?

GN: I do feel like, initially, it was distracting. It was hard to know when you’re talking about a movie and when you’re talking about yourself. It can be confusing and no one’s going to hang for this without an anchor, so when I’m writing about Freddy Krueger, I’m writing about Nightmare Man. I feel like Freddy is one of those monsters we were hardwired to know. It’s a nice reminder to the reader that this embedded. If there’s a movie someone hasn’t seen like, that’s cool, they won’t feel lost because that’s another thing you get with distance. You don’t need to see the movie.

ML: My final question and you’ve kind of lead into it is you know so much of this is about mourning, and you have a couple of sections about finality and limbo.

The difference between saying so long, instead of goodbye. After a year, where there has been a lot of mourning, a lot of trauma, and a lot of saying so long or goodbye has the pandemic kind of infiltrated your thoughts about how you are processing and framing trauma within the book?

GN: In some ways. The book was picked up in July 2020 so we were well into the pandemic. At one point I joked to my husband that if I tried to write a pandemic essay to go into this book, it would take me another year. Even longer, because were still in it. If anything, when thinking about saying goodbye or saying so long and figuring out different levels of grief, I do think there are variances throughout the book — where someone feeling or experiencing grief might feel less alone. My grief is not a special thing. It’s mine, but one thing that makes me feel less alone is the notion of other people experience loss.

Acknowledging the humanity of loss, suffering, and grief is a really important part not only of the book, but of life. •