Sometimes, an idea can be so arresting that, for a time at least, we care more about the fascinating nature of the idea than we do about its feasibility or reality. This was how I felt when I discovered that one man (and a few others before and after him) firmly believed that the Earth is “hollow and habitable within.” The idea of a concave inner world that was as yet unexplored captivated me initially, but in the end, it was the man who believed this theory so doggedly who captured my attention.

John Cleves Symmes Jr. lived 200 years or so ago; I discovered a monument in his honor in a park in Hamilton, Ohio, a small city north of Cincinnati. I first learned of it when I was surfing Atlas Obscura and went to check out the monument.

The monument stands in a really run-down park; the monument itself has been defaced and a forbidding fence has been erected around it to prevent further vandalism. On its top is a bronze model of the “Hollow Earth,” with the openings a little scalloped, like you could easily walk down the slope from the icy areas of Siberia into the lush interior of the Earth. No one in Hamilton really cares about this guy, as far as I can tell; no one really celebrates him, but the monument still hasn’t come down even 150 years later.

John Cleves Symmes Sr. was the real estate mogul of the era; the area he owned, eventually sold off to different municipalities, includes Cincinnati, Ohio and all of its nearby suburbs, including the land that would be settled eventually by nearly a million people. Symmes Sr. was one of the “early adopters” of the middle of the country, making a killing and providing the prosperity that fueled his prominent family. Not the least among them was the alternate hero, John Cleves Symmes Jr., a nephew of the tycoon.

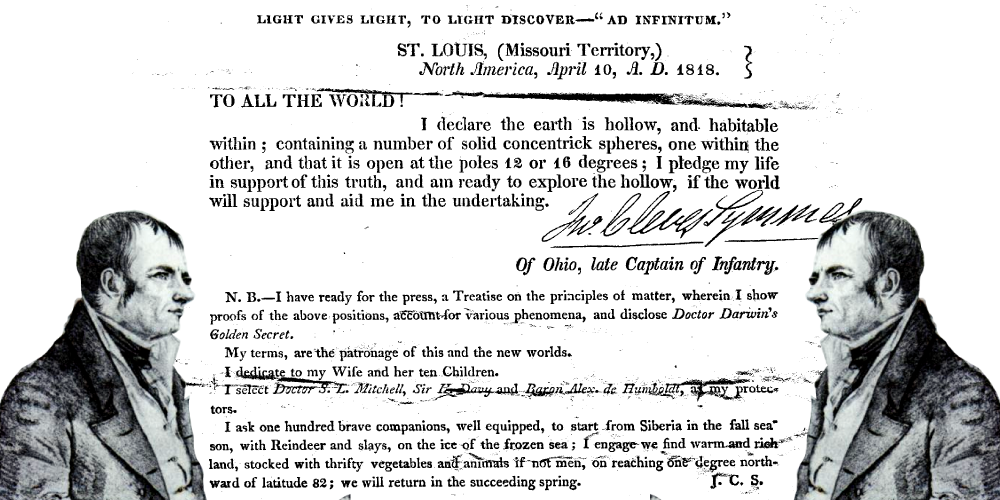

Symmes Jr. was a war veteran, but became known not for his military prowess, but instead for his voracious appetite for geographic and scientific study, as well as the theory he developed in response to that study. He only had a grade school education, but he read independently to the point where he could quote the best and most learned scholars of the day and of the past. The only problem was that all of the readings and study he did led him to one conclusion: the Earth as we knew it was less than half discovered, even in the 1800s, because it was actually “hollow and habitable within.” He thought that there was an interior surface of the hollow Earth that was as yet undiscovered by us exterior-Earth dwellers, and he thought it best if we set about finding that land as soon as possible.

Symmes Jr. formed this belief through his years of study and rationalized it with nearly every bit of evidence he could find, bending the explanations of observation to prompt him to feel that he was always on the right track. One example, cited at Time Blimp, is that he saw natural debris and driftwood floating up on shore at beaches as a sign that somewhere, a giant hole was open, allowing things from the interior of the earth to bubble up and show signs of life within. Never mind that the same debris could have come from half a mile upstream during the latest thunderstorm; Symmes Jr. defied the most glaringly simple explanation in favor of a ridiculously complex one. He clearly shaved with a rusty version of Occam’s Razor, which should have created an assumption that a theory that required this much complex working and reworking was probably deeply flawed. However, given that he couldn’t muster up the funding to head north, he allowed misallocation of scientific facts to provide a logical train that derailed frequently but without any loss of confidence.

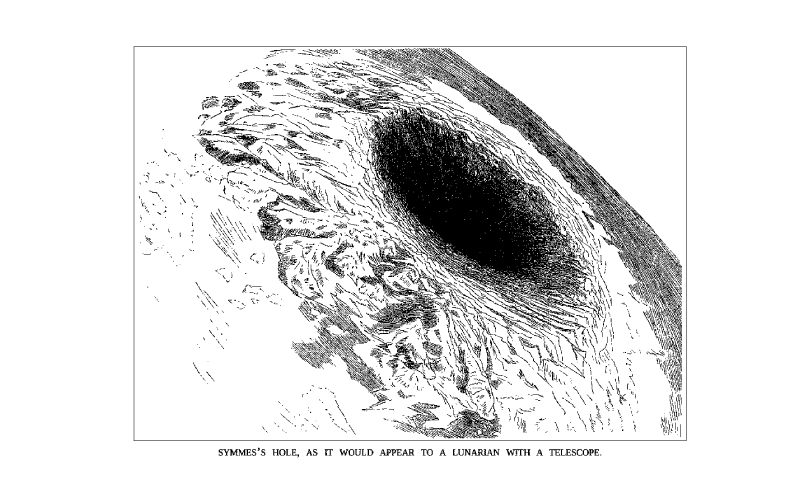

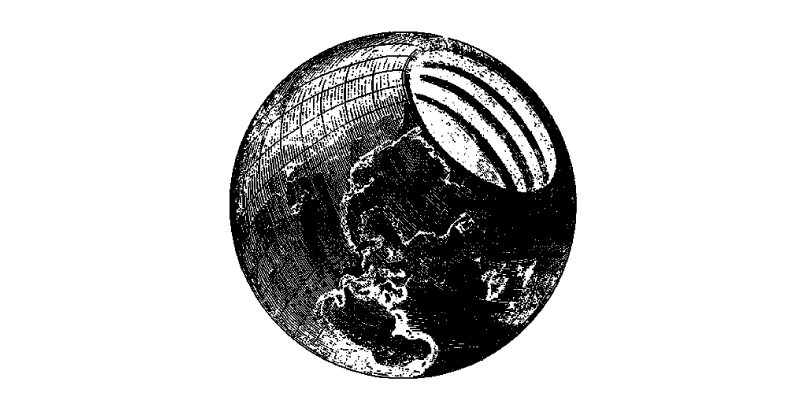

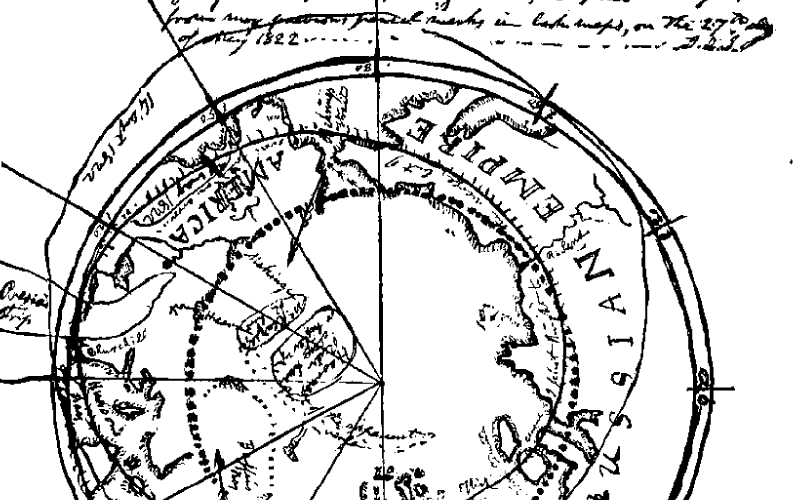

For a while he thought that there were many “concentric spheres,” each of which held potentially habitable land, accessible through what was dubbed a “Symmes Hole,” one of two absolutely enormous maws on either end of the Earth. He conjectured that these apertures were not exactly centered but amounted to be cut off the sphere of the Earth from 68 degrees of latitude in Lapland, at an angle to 50 degrees in the Pacific Ocean. The southern opening would be even larger, at 34 degrees south out to 46 degrees south — truly staggering, given that regions farther south than those latitudes had already been explored. According to Duane Griffin, a modern geography researcher at Bucknell University who took an interest in the historical record on Symmes Jr., this also would prohibit the flora and fauna that Symmes Jr. asserted thrived inside the Earth; such holes, while enormous, wouldn’t allow for enough sunlight to keep anything alive and warm past the entrances.

Still, for whatever reason, Symmes Jr.’s super-specific points said that if you took the extensive journeys from the United States North to a frozen and sparsely inhabited part of Europe, he claimed the adventures would round the lip of the hole and would discover a temperate land within the Earth. In his last three years of life, he simplified the theory to the whole Earth being one hollow shell, with the interior being one big convex landmass for everyone to settle. The simplification didn’t seem to bother him; the need for evidence only bothered him when it suited him to make a change. Strangely, he seemed to have gained popularity as a speaker for just such bumblings: if he was willing to revise his initial claim, didn’t that make it seem like he was an authentic man of the people who admitted his mistakes? Perhaps this very quality should have instead put a stop to his unverified nonsense theories earlier, but it instead seemed to bring more people out to his public lectures on the topic.

At the same time, when refuted, Symmes Jr. turned often to a simple truth: though some explorers had penetrated the “high latitudes,” there was little repeated evidence of exactly where in the cold northern lands various explorers had ended up. By his time in history, Symmes was able to contradict any naysayers by pointing to the need for more exploration, more study, to either prove him definitively right or offer “actual” proof that he was wrong. There have been many proof-positive moments in the last 150 years that show the theory to be wrong, but the core of the idea lives on in some small conspiracy theory groups, including everyone from Edmund Halley to modern Hollow Earthers.

The development of his idea is remarkable for a few reasons. One is that at no point did he treat it as an idea of fantastic creation; he spent much of his life giving informational talks specifically to persuade others to fund an expedition for him and 100 men to the North Pole — “just let me prove this to you,” Symmes Jr. seemed to be saying all the time. While North Pole expeditions were probably an inevitable curiosity, Symmes Jr.’s enthusiasm is credited by some with having generated enough traction for later Robert Peary and others who ventured North to actually receive funding. Symmes Jr. didn’t live long enough to receive evidence he personally would have found incontrovertible, dying in 1829, without ever recanting his theory.

His writings read like the most committed of science fiction; really great speculation is always detailed and full of what author Karen Russell calls “Invisible Architecture” that makes the world believable while you are within it. One can start with his commitment to the specifics of where the holes began, but all manner of other phenomena — Griffin mentions temperature distributions, patterns of wind and ocean currents, animal migration, and the aurora borealis, of all things — were taken as evidence that there was a missing piece of the Earth that was showing up to him in a way that it hadn’t really shown up to anyone else. He had what argument analysts would call a surfeit of evidence and no warrants at all: his claim that the Earth was hollow was utterly disconnected from the many things he thought proved his point. Science fiction authors don’t have to create warrants for their beliefs because we accept their work as not real, as a chance to compare a fantasy idea to what we do know of the world without demanding that they align perfectly. By Symmes Jr.’s time in history, science was usually held to a higher standard, one where the theory had to be deeply connected to observable, related phenomena.

The difference between his enormous treatise on the Hollow Earth and the worldbuilding done in fiction seems to be that this guy really saw all of the speculative and observational scientific work he read as evidence. He thought, for instance, that the disappearance of great schools of fish every season only to return at another time was evidence that the oceans extended into the interior of the Earth, allowing the fish to make a Mobius-strip journey into the center of the Earth and back out again. Symmes Jr. somehow saw this explanation as more logical than fish simply swimming around the exterior of the Earth in the already-discovered oceans.

Symmes Jr. toured the states, acquiring a few tolerant wealthy patrons and a lot of support along the way despite being, according to reports, a truly terrible public speaker. It makes you wonder if people assume the sincerity of a message is stronger because the person cannot convincingly make a point about it. Even the government of the new United States was pondering checking out this theory, seeing if an essentially bottomless pit ran through the pole of the Earth. He just seemed so certain, so heedless of known scientific facts about how gravitation wouldn’t naturally create a bead of a planet, wrapped around empty space. He had an answer for everyone, even when it could be broken down to unrelated gibberish.

A strange side effect came from Symmes Jr.’s hairbrained pursuit of the poles; because so many people had been campaigning for public money to go toward the exploration, the way was paved for other scientists to seek funding through government means. Much publically funded scientific research may be tangentially linked to one kook in the 1800s lobbying to go find the interior of the planet. More specifically, the contributions to geographical understanding of Antarctica were quite connected to the original ask for a polar expedition, despite never finding a yawning hole through which people could enter the Earth, according to Griffin.

I would say he isn’t celebrated, but weirdly, there is a following out there. The podcast Bad Ideas featured him and talked about how “weird shaped Earth theories” are near and dear to their hearts. On the Arcana Wiki, the many influential writers who took this theory into their fiction and thus made it timeless are listed:

“Symmes’ Holes featured in Edgar Allen Poe’s novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket and his short story “MS. Found in a Bottle.” Edgar Rice Burroughs used the idea of a Hollow Earth as a setting for his Pellucidar novels, and his crossover novel Tarzan at the Earth’s Core used the device of flying an airship to the North Pole and entering the Earth through the Symmes’ Hole. Jules Verne played with the idea in his novel A Journey to the Center of the Earth, but he limited the Hollow Earth to merely an extremely large system of caverns accessible through a volcanic shaft.”

That’s the thing: even I am totally obsessed with this guy’s ideas. In an age when it was so hard to know much for certain about science, and claims had to be backed up with painstaking observations and mathematical calculation, and the observable Earth had been more or less mapped out, he dared to think there was more to discover and more to glean from the data in play. It’s hard not to love the possibility in his speeches. The thing is, though, that Symmes Jr. wasn’t operating in a place where he was harming human life by having crackpot theories; there is such a thing as an unsafe place for the willful rejection of facts. It could have gotten far uglier if 100 people had really packed one-way rations and trekked North with him; he was unsuccessful and thus really didn’t harm anyone in life, and in death, he provided a strangely lovely set of ideas to inspire wonder and creativity in others. When I see the monument though, old and graffiti’d in a park in Ohio, I cannot help but thinking that not all insanely held beliefs inspire; some of them cause actual harm.

A lot has been made lately of alternative facts, of people who passionately believe things that are later proven to be completely wrong. While the issues that arise from such willful moments of ignorance can make us feel like the internet age has brought us into an insane world of he-said-she-said, the truth is that it has been going on for a long time. “It” in this case is the behavior of doubling down, of leaning in, on the experience of being totally wrong. Even if we love the fiction that comes from these thoughts, doubling down on a wrong idea shouldn’t be something we ever praise.

The big bronze bead of a globe stands as a monument to how tenaciously a man held to a belief that, to all appearances, didn’t serve him in any undue way and yet couldn’t possibly have been true. I wonder how he would feel about having inspired fiction and wonder rather than having made a real scientific discovery; I wonder if he would really think that this modern world is less strange and wonderful than the one he envisioned, or if he’d be just as baffled and fascinated by all that we’ve discovered since 1829. I think he’d find some other pocket of unexplained world to theorize; we can’t help wanting there to be more mystery to explore. I just hope that the facts, as they stand, would be of some interest to him too. •

Graphics by Emily Anderson, images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.