Since Moses parted the Red Sea, being a Jew has meant having an escape plan.

Mine sits on a high shelf in my office. It’s an orange-and-gray camping backpack, its contents stacked by weight, following the advice of a YouTube video. If I had only minutes to skip town and head for the woods, I’d be in trouble: I need a step-ladder to reach it, and when I pull it down, the weight almost pulls me off balance.

But my destination isn’t the woods. On its way as I write, carving a path through the US Postal System like the hand of God through the waters, is a little red passport. It comes from a country I’ve never visited, through family I didn’t know existed until last year.

It will deliver me back to the place that would have killed them — in comfort, even in style, if I spring for the seat upgrade.

Which is absurd, bordering obscene. As I join the rich tradition of People Prepared to Escape — as I consider the ease, the convenience, with which I’ve planned my getaway — I have never felt more connected to my family. But I can’t tell if the mixture of horror and comfort I’ve felt getting here brings me closer to their stories, or much further away.

•

My family, to whom I am not related, has a history of escape.

One particular great-grandmother is the subject of foundational family lore: Growing up near Minsk at the turn of the century, she survived a pogrom — as Cossacks ransacked her home, she hid in her family’s oven. I’ve known the story of her deliverance so long that it feels less like personal history than genetic memory, like birds’ instinct to fly south in winter.

I’m sure she is in the back of my father’s mind when he tells me, at age thirteen or fourteen, that the most dangerous thing in a crisis is people. A few will be greedy, but many will be desperate. For this reason, our basement pantry is always well-stocked, and spread here and there throughout the house are little stashes of money and valuables. When the time is right it can all be quickly gathered.

My father is no Doomsday Prepper — growing up, the stashed supplies were mentioned only a handful of times, mostly in the context of a hurricane or blizzard — but it gave me comfort to know there was something waiting for us when we crawled out of our ovens.

I started my own escape plan, the orange camping bag, in the months after Trump’s election. I stored brown rice and toothpaste, a copy of How to Stay Alive in the Woods, and duct tape. I kept lectronics and chargers in the bulging side pockets for easy access.

I tested the shiny new camp stove on top of a metal trunk while my partner slept nearby. I didn’t fully understand how the lighter worked, and I, hesitating for several minutes, was convinced I would somehow blow the place up.

I felt overprepared and underprepared at the same time, and that seemed strangely right. In my guardedness, in the plan I was laying against whatever came, I was preserving a tradition.

The flame lit up blue and clean. I turned it off and shoved the stove into the bag, and the bag into a closet.

•

I don’t remember when my father told me he was adopted. It had never been a secret, and I’d always shared his disinterest in finding our biological family. My grandparents are my grandparents.

All the same, being Jewish comes with a grab-bag of potential genetic disorders, so when I received a 23andMe one holiday, I didn’t hesitate to spit in the cup. My results ticked off my genetic risks: nothing too scary.

Which was the end of the story for a few months, until the website 23andMe’s built-in messaging system pinged with a notification: A message from a man who said that, according to genetic markers, he was my grandfather.

I set up a dummy email address to communicate without giving away any personal information. He proved his identity by knowing my father’s birth name. He shared the story of too-young love that started it all, which would have felt like a cliché if it weren’t, suddenly, my story too.

He explained that he and my biological grandmother had stayed together afterward, gotten married, and produced two more kids.

In the space of a few emails and phone calls, my father had gained a biological mother, father, and two full brothers. And he didn’t know any of it: I hadn’t told him yet.

•

Long after this, I would learn about another great-grandmother, Valerie, born in Vienna, Austria, in 1923.

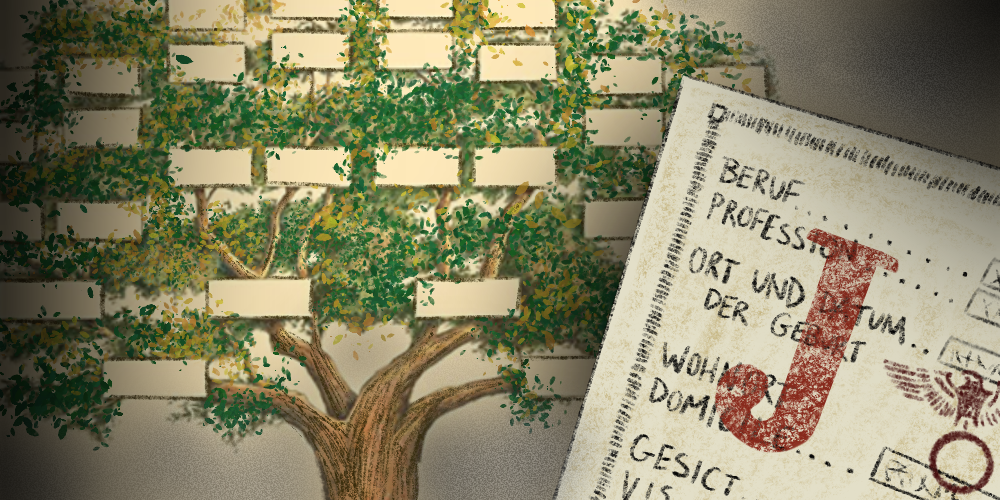

Nine days before Valerie turned fifteen, Nazis across the Third Reich launched Kristallnacht. Valerie’s mother took the sign, and four months later they boarded a train, bound for a boat, bound for America. Her passport is stamped with the Nazi eagle and a red “J.”

Her face around her eyes, gazing out from her passport photo, is my father’s. The handwriting in her signature is mine.

•

We had ordered dessert, and I still hadn’t shared the news. I’d written a script in my head, and edited it in real-time throughout the meal, but it felt too big to squeeze into some lull in the conversation.

Running out of courses, I finally told the story., He quickly paid the check, and we wandered the suburban streets so he could process. There weren’t many words for a while, just “wow”s — he became cogent again only when I said that his biological mother was ready to speak with him when he was.

The process took months. It started with a single email, saying first that he was happy and well, which must have been her secret hope for over fifty years.

That email produced a few more, and eventually texts, and finally, a phone call.

That call broke the dam: Not long after, he would board a plane to Atlanta, and for the first time, they would sit under the same roof and share a meal.

His brothers are both disconcertingly like him: One slightly less serious, one slightly more, all successful in their chosen paths, and all with the same mannerisms and blue eyes. On the phone or at the table, the years fall away.

•

In September 2019, the Austrian parliament passed the Staatsbürgerschaftsgesetz, the Austrian Citizenship Act, offering citizenship to anyone who could prove themselves “victims of the National Socialist Regime” — and their descendants.

This gave Valerie a new, posthumous identity: Beyond daughter, mother, and grandmother, she was now verfolgter Vorfahre, a Persecuted Ancestor. Her children were entitled to a de-Nazified version of the same passport she’d escaped with, and so were her children’s children, and their children as well.

We were in the depths of the pandemic as my father explained this to me by phone; I heard him pacing in tight circles in his home office while I paced in mine. I understood what the news meant: Austrian citizenship was European Union citizenship. It would let us travel to, work, and buy property in almost anywhere in Europe.

And like him, I grasped the deeper meaning. In a world taught to us by the old family history and the new, a world where circumstances disintegrate past the point of no return, where home is no longer safe, and even the bedrock crumbles — a world that felt dangerously close — EU citizenship could save us. If the moment came, we could board any plane at any airport and fly away, free and clear, and be more than refugees when we landed.

It was infinitely more feasible, and for that reason, infinitely more real, than living off the camping backpack stashed in my closet. And it had fallen into my lap.

•

The months I worked through the citizenship application process were held together by a feeling of dissonance. For a while, I thought it was the weird circularity of it all: Valerie’s escape out of Austria permitting my escape in. The bond between my father and his biological mother, legally severed at birth, now legally reconstructed as a hedge against the threat of death.

That was the most complicated piece, and the one that took the most time. State adoption records were unsealed, pre- and post-adoption birth certificates lined up, and confirmation given that these two legal versions of my father were one and the same person.

My process was easy: I ordered my required documents by mail. One of my new uncles proved my connection with Valerie in an impeccably written document I copy-pasted. I pulled down my mask to take my passport photo at the CVS.

My paperwork was organized, my emails with the Austrian consulate were friendly, and it was not until almost the end of the process that I realized the true source of my dissonance: I had planned for the end of life as I knew it from the comfort of my home.

And in that, finally, I felt myself testing my connection with the ones who escaped before me. Did my great-grandmother think about train schedules while she hid in her oven? Did Valerie’s mother ever feel comfort mixed in with her horror in the months between deciding to leave, and actually going?

They had hope, at best; I had an actual way out. I felt special and proud, like a kid who aced a spelling test. I felt ashamed, like a kid who cheated off his neighbor.

This giddiness must either be a universal experience of being Prepared to Leave, or an obscene privilege.

I bundled my paperwork in a manila envelope and brought it to FedEx. I bought first-class shipping and included a pre-addressed return envelope, so my documents — my proof of identity — would find their way back home. I balked a moment at the $70 price tag. Then I remembered that, in this plan I laid, $70 was the cost of a future for my children, and their children, and their children’s children, amen.

What a bargain. What a steal.

•

A few weeks ago I chatted idly with my father about using our shiny new EU citizenship to buy a place in Ireland; if we needed it, there would be no language barrier and the job skills would translate. In the meantime, we could hire a company to run it for us as an Airbnb, and generate some passive income as landlords before we became escapees.

My passport hasn’t arrived yet, but I know my papers are moving through the mail with Germanic efficiency. It’ll be here soon enough, but I have no plans for it. I’ll put it in the side pocket of my camping backpack for easy access. Then I’ll wait to need it.

That is, I’m realizing, easier said. There is a tension between knowing that there is a red line, and hoping you’ll recognize that line when you cross it. That tension feels old and care-worn, like an heirloom. I feel connected to my family, both the long-known and the newly discovered, when I test its weight.•