In 1910, a successful bacteriologist from Denmark put his medical practice on hold to focus on hindering the progress of expressionist art. Carl Julius Salomonsen thought that modernism in all its forms was pathological. Defective eyesight, he argued, was to blame for expressionist aesthetics. He termed it “ophthalmic psychosis,” and designated cubism and Dada poetry (with its cut-up sentences and word salads) as ancillary symptoms.

Dysmorphism was the name of the new syndrome he’d invented — from the ancient Greek dys– for bad or unseemly, morph– for shape or appearance, and –ism for its obsessive nature. The new disease hit a public nerve. To raise awareness, Salomonsen used the media and social channels of his day: large-hall public lectures and open letters to the newspaper. His public offerings spawned more printed letters in response, which warranted further response-in-open-letter. This battle-of-the-essays, in a new crisp translation, forms the body of the book New Forms of Art and Contagious Mental Illness, curated and presented for your morbid enjoyment and instruction by art historian, archivist, and translator Andrew Hodgson.

Dysmorphism, Salomonsen claimed, was a contagious illness, threatening to spread like an epidemic. The illness’s mode of transmission, he wrote, was not bacterial, but went invisibly from mind to mind: untraceable. Through the channels of empathy and a shared vision, he wrote, it could cause contamination via sympathism. The fact that its molecules could never be seen or isolated under a microscope only made the illness more spectral and dread-inspiring. To face down said spectral presences, a new transgressive custom popped up in Danish medical schools: for the end-of-year ball, graduating students would dress up as “dysmorphists,” decadent expressionists and dada artists prey to this putative disease. They would talk in Dada word salad, stumbling and falling all over each other. These proms were called “Dysmorfesten,” i.e. Dysmorph-fest.

We may smirk at this historical oddity and view it as just another ill-advised, ideologically motivated wrong-turning in the annals of Psychiatry. We now know that this was all mistaken, and it’s easy now to see how deliberately obtuse the doctor was about avant-garde art. Yet, there’s more to be gleaned from the wrong science of yesteryear. For one, there is its cultural impact: the fact that the theory was so popular, and one has to ask why, despite lacking a scientific basis, it gained so much traction with experts and the general public. Then, there is the unsettling vagueness that surrounds all knowledge about mental illness and the clever weaponization of that vagueness. There’s the art of swaying opinions, despite the inherent un-graspability of mental illness and its uncanny power to transform someone you know into someone you don’t know. There is the evergreen and ever-vague argument that individuals with mental illness are a threat to public health and safety.

That vagueness, that unknown, is still as pointedly weaponized against the mentally ill today as it was in this very locally Danish, very academic, and now very forgotten chapter of medical history. Not only did the doctor’s cranky ramblings kick off the so-called “Danish furor” at home. He also kept a fulsome international correspondence with other experts of his day. In his essays, he quotes from exchanges with the men of London’s Royal Society of Anthropology. In Britain at the time, Anthropology was a profoundly racist, ableist, classist, and openly eugenicist science. Anthropology’s aim was to categorize types of human beings, and to demote or disqualify some people from real humanity. By 1937, all of this theoretical spinning and conceptual work came to its grimmest possible outcome in Nazi Germany. Here, the nationwide collection and display of so-called “Degenerate Art” instigated the mass destruction of expressionist artworks, and the suicides and murders of the artists. Meanwhile, Salomonsen had died in 1924, thinking he had lost the battle against modern art.

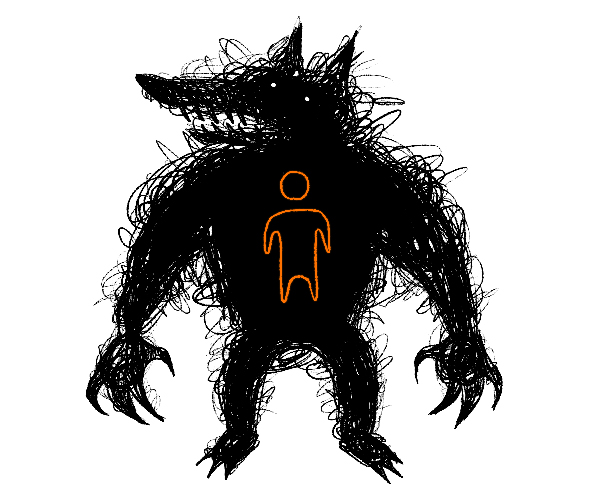

As small pieces of an ancient Roman temple built into a Christian church, the pillars and column heads of disproven scientific constructs have slithered down into today’s knowledge, re-purposed for newer science. In this case, we’re left with the word “dysmorphia,” frequently invoked in pop psychology. Today’s dysmorphia is understood to be the horrible sensation of looking in the mirror and seeing something ugly: a distorted self-image. We think of dysmorphia as a function of self-criticism, the fear of what we look like on a bad day. It can encompass the fear of our own self, or of our worst possible self, of which we have only a dim idea. In the tale of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, a criminal and beastly id replaces the fine doctor every night at nightfall. The story, like today’s body dysmorphia, plays with our fear of being replaced, as if there’s some closeted and awful Mr. Hyde lurking within us all, forever on the brink of leaping out.

Lycanthropy, in the tangled web of psychiatry’s many failures, sits perfectly next to Salomonsen’s dysmorphism. From the Greek lukos for wolf, and anthropos for human, lycanthropy was a condition characterized by the conviction that one was turning into a wolf (or, by extension, an animal of any kind). As a somewhat fantastical psychiatric condition, lycanthropy rings of medicine’s bewitched and bewitching historical roots in medieval magic and folklore. In the Dark Ages, husbandless village women often turned to the healing arts and herbal medicine as a way to earn a modest living, yet this also made them obvious scapegoats for any illness or madness at large. These narratives look back to ancient Greek and Roman mythology’s magical and demonic female figures of healing and medicine, women like Circe or Medea. Just like lycanthropy plays with the fears ingrained by hand-me-down myths of transformation, Salomonsen’s writings tap into a European collective memory of lepers, the fear of contamination, and the need to isolate those who are already contaminated. The dysmorphism thesis fanned the flame of ancient fears that distortive art could bring real disfigurement, and could usher in an age of cognitive and cultural decay.

Today, the lycanthropy diagnostic is still not entirely abandoned by science, no more than dysmorphia has left our psycho-linguistic registers. Rather, the word has traveled in its semantics. Like a sonorous vessel, the word now conveys new meaning, about body image and mirrors in the modern world. And yet, the old meaning has not entirely vanished. In the history of knowledge, etymologies of words can be viewed like permafrost: a word may no longer mean the same thing as it used to, but it still is host to all the meanings it has ever had. No matter how dormant, the awful toxic thoughts are still in it, apt to break out again. If we want to shift the paradigm on art and mental illness in society today, what better way can we find, than to review our words, one by one? The old meaning still sits there, like a cairn on a road. In the case of dysmorphia, it leads back to an old crank in Denmark, who was intent on dressing down modernist art, and accidentally helped the Nazis kill lots of amazing artists.•