This year, the 50th anniversary of the assassination of JFK, affords another opportunity to mourn the death of an optimistic, can-do America. America today is hobbled by schism and ineptitude. But then, as the many books about JFK released this year make clear, Camelot wasn’t what it was cracked up to be either. That’s part of the point. In a postmodern age, you can’t look at the world without irony — even when looking back on it. Everything, even our history, seems soiled.

But visit The World of Coca Cola at Pemberton Place in Atlanta for a taste, figuratively and literally, of an un-ironic America. It’s significant that you can’t tell a Coke slogan from 1924 (“Refresh yourself”) from one from 2010 (“Twist the Cap to Refreshment”) and whenever politics gets hinted at it is mostly to underline how apolitical Coca Cola is. Consider: “The Great National Temperance Beverage” (1906) or “America’s Real Choice” (1985). Coke promotes a chaste sort of pleasure, as in: “Enjoy life” (1923) and a modest patriotism as in: “Red, White, and You”(1985). Time and the tumult of history have no bearing on such inoffensive slogans as: “For People on the Go” (1954), “Always Coca Cola” (1992), “Make it Real” (2005), and “Life Tastes Good” (2001). This extends to that expression of global outreach, “I’d Like to Buy the World a Coke” amended into the musical number: “I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing (in Perfect Harmony).”

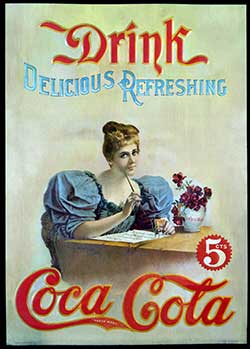

A song like that, emanating from a multinational corporation, might make you squirm (especially if you took a Postcolonial Studies course in college), but you’d have to be Scrooge to make a fuss at The World of Coca Cola. All those little children posing with the Coca Cola Polar Bear are cute; the old advertisements showing women in aprons and men in fedoras are nostalgia-inducing; and the chance to sample Coke-related drinks from around the world makes for comparative interest not to mention a pleasant, sugar-induced buzz.

The drink itself has a tortuous history that The World of Coca Cola has edited into simple and heroic form. It had its beginnings in 1886 as the work of Colonel John Pemberton, a Georgia pharmacist. Not mentioned in the promotional literature is that Pemberton was on the Confederate side of the Civil War and, after being wounded in the Battle of Columbus, Georgia, the last battle of the war, became addicted to morphine. Hoping to alleviate his addiction, he developed Pemberton’s French Wine Coca, which he marketed as a patent medicine and which gained particular traction among neurasthenic women. As temperance legislation began to be enacted in Georgia, however, Pemberton produced a non-alcoholic form of the drink, added carbonation, and had it sold at soda fountains. Unfortunately, he had failed to kick his morphine habit, and, short of money, sold all or part of the product to another druggist, Asa Griggs Chandler, who, with his son, went on to reap the serious profits.

Various versions of the drink as well as ownership disputes make it hard to fully trace the Coca Cola genealogy, although the World of Coke makes a point of making everyone involved an apostle. The linkage of Coke to cocaine is left unaddressed, even while the name of the drink rubs this in your face. We don’t actually know how much of this substance was used in Pemberton’s product — though presumably this was the real secret that gave Coke an edge over other beverages. It is interesting to note that cocaine was viewed at the time as a “cure” for morphine addiction. (Freud praised cocaine’s curative properties in the 1880s, and became addicted to it in the process). But the company doesn’t go into any of this, possibly for fear that younger visitors might want to purchase the stuff undiluted on the local street corner.

Part of what makes Coke’s triumphal history go down so easily is that no one around today was alive before the beverage existed. Coke is “real,” as the promotional slogans remind us, because, artificial sweeteners, colorings, and preservatives aside, it has endured in more or less the same form for as long as anyone can remember. It is moving to see those old, round-cornered Coca Cola machines and those small, green-tinted glass bottles. The red on white Coca Cola script is a kind of Madeleine experience for childhood. Even if you never experienced anything like the America of Norman Rockwell (who did many of the Saturday Evening Post advertisements for Coca Cola during the 1940s and 50s) there’s something about that Coca Cola script that makes you think you did. I suspect individuals around the world feel this, even if they hate everything else that America stands for.

Coke, if I may extend my musings further, is the closest thing that exists to a religion of Americana. Not an American religion, but a religion devoted to the idea of America — which is to say, to those Norman Rockwell scenes of homecoming, fly fishing, and presents under the tree. Disney might be compared with Coke in having something of the same religious aspirations, but Disney has a more complicated apparatus — movies and theme parks (a visit to one of which is liable to bankrupt a family of four), not to mention the dubious figure of its founder, Walt Disney, a misanthropic anti-Semite (OK, Coke’s Colonel Pemberton was a drug-addicted Confederate soldier, but never mind). To worship at the altar of Coke, you just have to like the drink and put out the paltry sum required to buy it — which, even if it may produce rotten teeth, diabetes, and obesity, isn’t creating centuries of civil war and ethnic cleansing. It tastes good and it’s refreshing, especially after you’ve spent the afternoon trying to assemble an IKEA cabinet or five hours in heavy traffic to eat overcooked turkey at your Aunt Leona’s.

The World of Coca Cola is a temple to the religion of Coke and, as such, includes the requisite religious service. When you enter, you are herded into an auditorium to view a Coke cartoon. This stands for the liturgy. I am not partial to cartoons in general, but the Coke cartoon is the most awful cartoon I have ever seen. Just to give you an idea: It opens with an MC, a cartoon puppet version of a minstrel, who is wearing a waistcoat but no pants, and who is backed by a group of overweight chickens evocative of a Motown girl group. The MC has an apparently female sidekick, who resembles a cross between a firecracker with a face and Miss Piggy if she were run over by a steamroller. More than that, I can’t tell you — the cartoon was utterly incoherent, if full of blaring music and frenetic movement. This supports Coke’s religious status. Religions are supposed to have incoherent story lines. It’s your job to impose meaning.

Our live host for The World of Coca Cola had the dark-rimmed glasses, high-belted pants and heavy-soled shoes of a Mormon missionary. He also had the gift of tongues — or at least for saying hello in a dozen or so languages. He announced that the cartoon we had just endured was about to be retired and replaced with a new one. He didn’t say why. Religions don’t explain themselves.

The Museum itself contains the artifacts and rites associated with the cult. In this case, old advertisements, old bottles, and assorted other memorabilia. The crafting of a religion has as its basic premise the idea that nothing is too trivial to have significance — everything must be preserved and parsed. If you exhibit an item, say a bottle cap, with enough reverence and in a nice enough glass case, people will find it interesting and want to take a picture of it.

There must also be a mystery for Coca Cola to qualify as a religion. The formula for the drink serves this purpose — an idea that got a boost from a marketing calamity that occurred almost 30 years ago. In 1985, concerned that America’s taste in soft drinks had moved to the sweeter side (where Pepsi resided), “New Coke” was introduced. New Coke had appealed to the company’s focus groups but was vehemently rejected by the larger, consumer public. Protests were staged in which New Coke was poured down sewer drains, and much ink was spilt describing how upset the soft-drink version of Joe Sixpack was at having his beloved non-alcoholic beverage tampered with. If you excise all the Latin or the Hebrew from the religious service, you destroy the mystique; you make things too easy — in the case of Coke, too sweet. The outrage that resulted from the retirement of old Coke came as a surprise to company leaders, but it didn’t take a marketing genius to realize that it could be capitalized upon. Coke Classic was revived 79 days after New Coke was introduced, and New Coke was quietly retired soon after that.

The Coke Museum spends a great deal of time talking about Coke’s “secret formula,” trying to whip this idea into something akin to the Trinity or at least the Virgin Birth. We learn, for example, that only a select number of people know the formula — or perhaps know only parts of it in the way revolutionary cells operate without full knowledge of the larger sacred mission. The Museum features an iron vault where the secret formula is presumably held and in front of which you can have your picture taken.

The last stop in the World of Coca Cola is a large room with lots of soda dispensers, where you can sample Coke-related drinks from around the world. This portion of the visit is likely to disarm even the most cynical visitor. You’d have to be a complete kill-joy like Cuba and North Korea (the only two countries in the world that presumably don’t sell Coke) not to get excited sampling Coke products from Uganda, Chile, and the entire European Union. This is what Coke’s high priests — i.e., its marketing experts — count on. • 9 December 2013