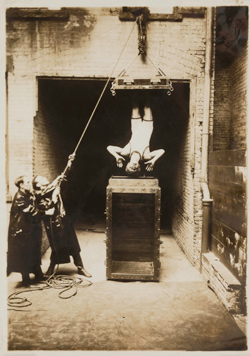

Harry Houdini’s escape trunk stands in the Jewish Museum like a coffin. “Embedded in Houdini’s ventures were competing ambitions,” says the wall text in the museum’s new “Houdini: Art and Magic” exhibition, “he simultaneously courted mortality and the triumph of life.” There’s a lot of metaphor in a trunk: adventure, travel, excitement, secrets. Houdini turned his trunk into a symbol of resurrection. Houdini’s audiences couldn’t know what tricks went on inside that trunk after he had allowed himself to be locked in and the curtain was closed. But some part of them believed that when Harry Houdini burst free, undefeated and smiling, he had shaken hands with the Grim Reaper and spat in his eye. Harry Houdini met death and came back to tell the tale.

- “Houdini: Art and Magic” Through March 27, 2011. The Jewish Museum, New York.

There are many things to say about Harry Houdini, and one is that he really loved his mother. Her death in 1913 devastated him. As anyone who has ever lost a loved one knows, the hardest thing may be the unbearable, suffocating absence. Houdini wanted little more than to hear just one word from his mother again and, in his grief, started to think it was possible. In Houdini’s day, a Spiritualist movement had taken hold in America and Europe, led by self-appointed mediums who convinced a grieving public they could conjure the dead. The Spiritualists held séance sideshows and passed around double-exposure photographs to show ghostly beings lurking about.

After the death of his mother, Houdini became increasingly interested in “spirit phenomena.” Interested, but skeptical. Houdini was the master of illusion after all, and in his youth had even dabbled in a few paranormal spectacles himself. Still, the death of his mother made some part of Houdini wish that he too could be a believer. So he suspended his own disbelief and set off on a quest to answer the question that so plagued him: Is there an afterlife?” “I was brought to a full consciousness of the sacredness of the thought,” he wrote in A Magician Among the Spirits, “and became deeply interested to discover if there was a possible reality to the return, by Spirit, of one who had passed over the border and ever since have devoted to this effort my heart and soul and what brain power I possess.” After years of following the Spiritualists, attending the séances, examining the photographs, the answer he came up with was, No. There isn’t an afterlife. The Spiritualists, he decided, were deceiving their audiences in the most cynical way. The illusionist Houdini then embarked on his second career as debunker of false illusionists and set out to destroy the Spiritualist movement. “I was brought to a realization of the seriousness of trifling with the hallowed reverence which the average human being bestows on the departed, and when I personally became afflicted with similar grief I was chagrined that I should ever have been guilty of such frivolity and for the first time realized that it bordered on crime.” Spiritualists were not just hoaxers, they were criminals, taking advantage of people at their most vulnerable moments and pocketing the profit. Moreover, Spiritualists tricked people into believing what Houdini knew in his heart was false: that death could actually be cheated.

In setting up a distinction between honest magic and deceitful magic, Houdini emphasized the way in which magic is a craft. Honest magic takes devotion; you can’t get it on the cheap, with little toe-rapping tricks on the floorboards and claims of psychic powers. Much of Houdini’s death-defying magic stunts have little to do with tricks at all and less with supernatural abilities. Houdini would practice new magic stunts obsessively, honing his body into an instrument of entertainment. He was an athlete, a dancer, an actor. In Houdini, art and artist were one. Houdini painted a visual spectacle of himself as magnificent and startling as any painting by Bosch, inspiring as any icon. Magic, Houdini was saying, is a worldly pursuit, improved by skill, training. It might be dazzling, confusing even, but real magic is not mystical.

At the core of Houdini’s magic was the theme of liberation: liberation from jail, from poverty, from the faceless immigrant’s identity Houdini shared with his audiences. Houdini began his career with prison-break shenanigans, handcuff escapes, and lock breaking. His posters shouted, “Houdini, The World-Famous Jail Breaker and Handcuff King! Houdini, the Justly World-Famous Self-Liberator!” (This from a man who would publish a book exposing the tricks of famous criminals. The line between honesty and deception for him was complicated indeed.) He was the magician of the people. Average folks watched mesmerized as Houdini slipped and shimmied his way from fetters, becoming what was for them the most otherworldly creature of all: a free man. Being a symbol of hope for the masses gave Houdini’s tricks a certain justification, an honor even, one he thought the shifty Spiritualist movement was devoid of. People trusted Houdini. Even as he fooled them.

In asking audiences to suspend their disbelief only to give them, in return, the unbelievable, magicians get to one-up religion and science. Magic has no doctrine. It doesn’t give you answers, doesn’t tell you what to believe in. Rather, it accesses your desire to believe. This is magic’s power. Magic seduces you into the unknown and leaves your imagination to run rampant, like an escaped zoo animal. Imagination might be the most terrible and wonderful thing about humans. Turn off the lights, give us a conundrum, and our brains will come up with the craziest notions — sometimes shameful, pointless, cockamamie notions. A successful illusion can lead our questioning imaginations to answers we never would have considered previously — even to the supernatural. “…How easy it is for even a great intellect, faced with a mystery it cannot fathom, to conclude that there is something supernatural involved,” Houdini wrote in A Magician Among the Spirits. You could say that religion and science fill up the spaces where imagination otherwise holds sway. Magic, on the other hand, opens all that dangerous stuff in our minds back up again. To their audiences, magicians say, if we just let go of certainty altogether, surrender to our imaginations, we can explore the unknown without having to explain it. And what is a greater unknown than death? Surrender to imagination, says magic, and you might experience death, too, if only for a moment. Thus the thrill, the liberation, of Houdini’s death-defying magic. And also the thrilling, death-defying flimflam of the Spiritualists.

Perhaps, in Houdini’s skepticism of the Spirtualists, there was a little shame, shame in the knowledge that he was not that different from them. But I think he was also angry with the Spiritualists for doing such a good job of deceiving others and such a bad job of deceiving him. Houdini was angry because he too wanted to feel the liberation of deception but could only be the deceiver. “My professional life has been a constant record of disillusion,” he once said, “and many things that seem wonderful to most men are the every-day commonplaces of my business.” It’s tricky when you’ve devoted your life to manufacturing marvels — you’ve got to dismantle life’s wonders, see how they tick. And once you control magic, surrendering to it becomes much harder. All the death-defying tricks he performed could not convince Houdini that death could be defied. Houdini’s death-defying acts weren’t just about thrilling his audiences. Maybe they liberated Houdini from “the wonderful” altogether and allowed him to experience life, and the simple, brutal, thrilling act of survival, as the most amazing wonder of all.

Every Halloween, the day on which Houdini died, people gather in hotel rooms and graveyards around the world to conjure the spirit of Harry Houdini. It’s ironic, but fitting, too. Houdini and his wife Bess once made a pact that, if his spirit returned to her after he died, the spirit would say “Rosabelle believe” and then she would know it was really him. For all his skepticism, there was a part of Harry Houdini that never completely lost hope in life after death, never completely lost hope that he would see his mother again. And when he did, he could ask her what he most wanted to know: Is there an afterlife? And probably she would answer what Houdini always suspected: Yes. If you believe in it. • 29 October 2010