Should Michelle Obama be angry because she was declared the world’s most powerful woman? Or, if not angry, maybe, at the very least, a little bit annoyed? I hope that she is. I was — not because I find her lacking in power, but for the same reason that I scrunched my nose at the presence of Maria Shriver, Carla Bruni-Sarkozy, and Sheikha Mozah bint Nasser Al-Missned: first ladies all. They are accomplished, to be sure, but Forbes’ list gave only a nod towards their professional lives and philanthropic activities: In this list their power derives from their husbands’.

For Michelle Obama, that’s the man she called “sweet and pathetic” while she was a guest on The View (June 18, 2008), almost five months before Barack Obama was elected to be our POTUS.

Pathetic is how I’d describe the rush of the women hosting the show as they leapt to do damage control. “Empathetic,” came the chorus, with Whoopi Goldberg spelling out, “E-m-p-a…”

I’m not so sure that empathetic is the right word to describe a husband who leaves his wife alone to deal with an overflowing toilet — as Michelle Obama described in a speech (April 16, 2007), “I was scrambling around to reschedule being at a 9:00 meeting and Barack, love him to death, put on his clothes and he left!”

Maybe if she hadn’t been “scrambling,” he would have changed his schedule?

Ah, well, overflowing toilets are one problem she won’t have to worry about for a long time, not at their current address.

I mention these domestic details because Michelle Obama’s choice as the most powerful woman is linked with her husband’s power. If John McCain had been elected President, would Michelle Obama have been deemed the world’s most powerful woman? No matter how intense a fan you might be of this First Lady, you know the answer.

Putting aside for the moment all questions about (and objections to) the isolation of women in the creation of lists like this — not the 100 most powerful people, but the most powerful women — I’m left staring at the particular composition of this year’s 100: intellectuals, entertainers, business women, and wives. OK, not just wives, but wives of political leaders.

This year’s Forbes list serves as a reminder of how a woman’s position in the world depends on her choice of mate, something that’s easy to forget in 2010.

The list’s entry on Michelle Obama is accompanied by her formal portrait by Joyce N. Boghosian, released by the White House a month after the inauguration in 2009. I had barely glanced at it before.

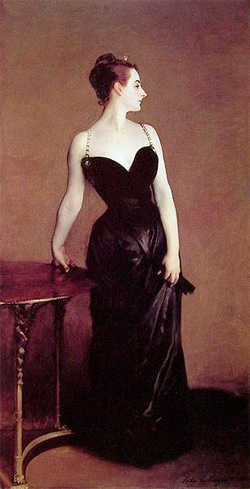

Seeing it again with Forbes’ declaration that the First Lady is the most powerful woman in the world, I became conscious of echoes of the now famous — once infamous — portrait by John Singer Sargent, “Portrait of Madame X” (Madame Pierre Gautreau, 1883-84). Both women are wearing black dresses, both are posed in a contrapposto stance with one hand on a round table. The similarities of the two portraits, however, make the differences between them even more striking, even discounting the busy background of the White House’s Blue Room.

The table in Sargent’s painting is empty and dark; the table in the White House portrait holds a huge bouquet of Casablanca lilies and white tulips. It may be a coincidence, but in the language of flowers the bouquet has an appropriate message. The Casablanca lilies mean “celebration” and the white tulips suggest “worthiness.”

In Sargent’s painting, Madame X’s face is in profile; Michelle Obama faces forward and her gaze meets the viewers. Madame X is not smiling; Michelle Obama has a full smile. Madame X clutches the back of the table, thumb on the table top; Michelle Obama rests the tips of four fingers on the white table top, with her thumb grazing the edge of the table. Madame X stands just beyond the widest part of the table so that although she is not entirely behind it, the table stands in the foreground between her and the viewer, making her more remote; Michelle Obama stands a few inches away from the table about the same distance beyond its widest point as Madame X is in her portrait. As the First Lady reaches out to rest her hand on the table’s surface, it is almost as though she’s touching the table to make a physical connection with something. The fingers of the left hand of Madame X are curled and hold fabric. Michelle Obama’s right arm falls at her side, her fingers in a slight curve.

But in the context of power, the image of Michelle Obama in the official portrait presents, like that of Madame X, a mixed message. Michelle Obama’s head is not at all tilted; moreover, her gaze is direct connects with the viewer. In contrast, her left hand rests on the table, apparently tentative as it connects with something solid, which suggests vulnerability. Her right arm is at her side, seemingly not quite at rest, as though she’s about to raise it to reach out.

What, if anything does this pose mean without some inside knowledge into the conversation between the subject and the photographer? Without that knowledge the buzz has been about the First Lady’s wristwatch (supposedly a Cartier tank), pearls, and sleeveless black dress (Michael Kors), hairstyle, and her manicure, all of which can be deconstructed — and have, even to the shaping of her eyebrows. Her choice of sleeveless dresses in winter received lots of press early in the President’s term.

It’s difficult for me to imagine that a person as sophisticated as Michelle Obama would not have wanted some say about her pose; surely she would have been conscious of all the subtleties of body language within the context of an official photograph. Perhaps even the gap between the dress and her shoulders was a conscious decision as part of a carefully constructed persona, something to make the female viewer want to protect her rather than feel threatened.

The First Lady certainly would not have wanted to project to viewers of the portrait rage of any sort, and certainly not feminist rage, which would be certain to alienate more than half the population. If she had felt any anger over the attribution of power being a function of her being married, it’s better that it be kept out of sight — much as her wedding ring is in this photograph.

Like every woman I have a photo of myself in one of my little black dresses. It’s a black-and-white candid snapshot taken at a party when I was in graduate school. It’s one of my favorite pictures of myself. I’m wearing a sleeveless number that I sometimes wore with a blouse. I’m seated, leaning toward someone across from me, my hair tousled, chin thrust forward, laughing. I don’t remember what was so funny, why I was so happy, or who took the picture. Because I don’t know the facts, I’m free to speculate, to read the photo of myself as I would that of a stranger, a young woman as happy as any young woman can be, happy in youth’s willful, necessary, ignorance of all that lies ahead. • 27 October 2010