“The Written Image” was an exhibit of German Expressionist art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. But it was not the exhibit of German Expressionism you might expect to see — none of Ernst Kirchner’s lurid scenes of degenerated Berlin society smeared across the streets. It was a show, rather, of portfolios, periodicals, works sketched on single sheets of paper. Featured among them were the so-called “wordless novels.” In one glass case was a 1926 copy of Frans Masereel’s My Book of Hours.

Frans Masereel was a Flemish artist whose primary medium was the woodcut. The woodcut genre thrived in Europe during the interwar years. Masereel and his contemporaries were drawn to woodcuts as they were to cartoons and silent film, media in which images were dominant and words were few. This was appropriate for a generation of Europeans who had given up, after the horrors of WWI, on the usual explanations. Expressionists struggled to speak the unspeakable, to express the inexpressible. In 1910, the Czech art historian Antonin Matějček placed the goals of Expressionism in opposition to those of Impressionism. “An Expressionist wishes, above all,” wrote Matějček, “to express himself… [an Expressionist rejects] immediate perception and builds on more complex psychic structures…” Impressionists paint the external world as it appears filtered through the human mind. With Expressionism, art was to come from within the artist — to burst forth from the artist, directly and honestly. Impressionists painted their perceptions. Expressionist painted their feelings; some said, their souls.

Frans Masereel developed his woodcut style while working as a political cartoonist during the Great War, in self-imposed exile in Geneva. He wanted a medium that was both striking and simple enough to convey the realities of his strange and terrible times. Masereel liked the roughness of the woodcut; he felt it did a good job expressing the passions of the common man. Masereel studied the woodcuts of the Medievals that were printed on prayer books and playing cards made for the unlettered masses. Toward the war’s end, Masereel began to make his own woodcut books. He called them roman in beelden or “novels in pictures”. Almost at once, Frans Masereel was recognized as the master of this newly popular art form: the wordless novel.

Masereel’s first attempts at wordless books – The Dead Speak and Arise Ye Dead (1917) – tried to assimilate the brutality of the war. (Arise, You Dead, Infernal Resurrection is a typical image: Two headless bodies carry two heads on a stretcher. One head wears a German helmet; the other a French képi.) But when the war was over, Masereel turned to more archetypal subjects: Man, God, Nature, The City. His art was about, and for, the men, women, children, plants and animals of Creation lost in a mad world. In 1918, Masereel published 25 Images of a Man’s Passion (25 images de la passion d’un homme, 1918) It was a precursor to his masterwork My Book of Hours: 167 designs engraved on wood which, for American readers, would come to be known simply as Passionate Journey.

Arise, You Dead, Infernal Resurrection by Frans Masereel

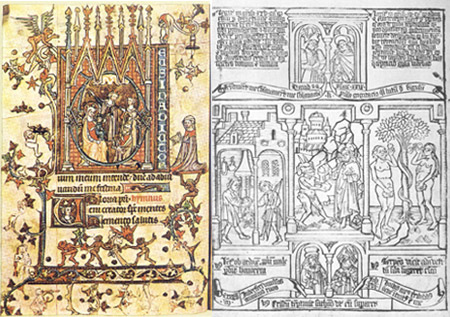

Books of hours were books of Christian devotion popular during the Middle Ages. A typical book of hours contained prayers and hymns and readings and a calendar of Church feasts. Books of hours gave structure to everyday devotion. Many books of hours were highly fussed-over illuminated manuscripts that only the rich could afford, with miniature paintings depicting the Passion of Christ or the Life of the Virgin, or landscapes showing the passing of seasons. Masereel’s book of hours was more of a Biblia pauperum, a Pauper’s Bible. These were common printed block books often used by parish priests as teaching aids. In early Biblia paupera, illustrations were accompanied by little, if any, text. Sometimes, words scrolled out of the characters’ mouths just like they do in comic strips. Text and images were carved on a single woodcut for each page; most illustrations were left uncolored. Masereel adopted this simple, colorless technique for his own work. He took the idea behind the “miniature” seriously as well. The original illustrations for My Book of Hours were just 3½ by 2¾ inches, small enough for a reader’s coat pocket. It, too, was book of devotion that could be meditated upon while, say, riding a streetcar or during a lunch break out in a field.

Left: A page from a 15th-century Flemish book of hours. Right: A page form a 15th-century Biblia paupernum

“Look at these powerful black-and-white figures, their features etched in light and shadow,” wrote Thomas Mann in his introduction to the 1926 edition. “You will be captivated from beginning to end… Has not this passionate journey had an incomparably deeper and purer impact on you than you have ever felt before?”

My Book of Hours does not follow a traditional plot, nor is it a series of unrelated pictures. The protagonist “does” many things, but we are meant to focus on his experience more than his actions. Masereel’s themes are wandering, loneliness, exultation, joy, boredom, frustration, anger, love, death. The story is a spiritual journey. The journey, thus, does not progress toward a tidy moral. Though the images in My Book of Hours are allegorical, the book is not a parable. The pictures spiral into each other, fall into each other’s arms. And yet each scene in the life of Masereel’s protagonist is complete, because the protagonist feels each experience completely.

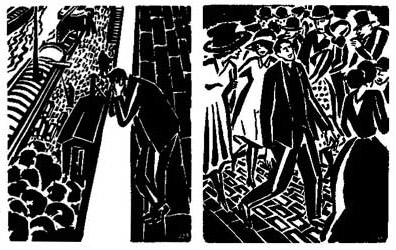

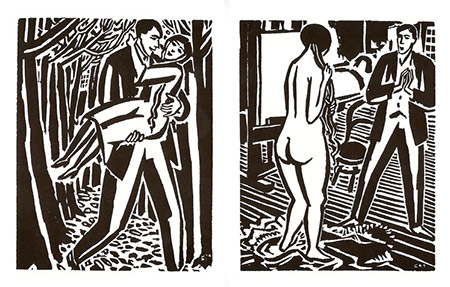

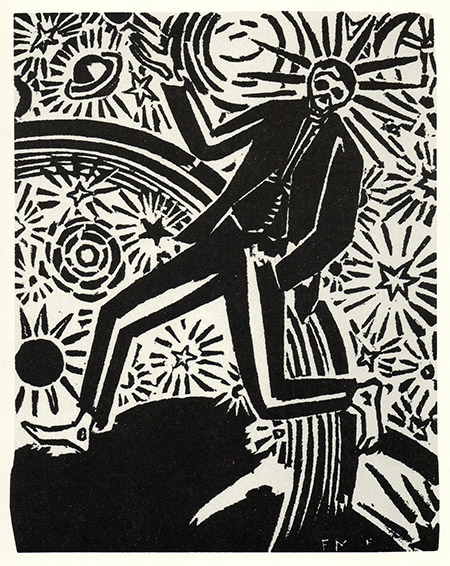

Two pages from My Book of Hours

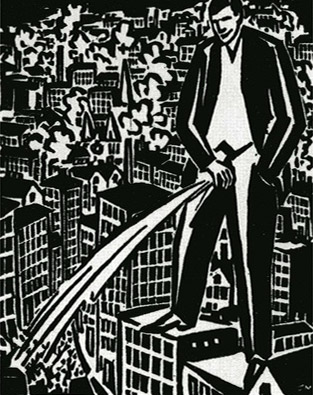

In the first image, we see a young man, leaning out of a train window. He is waving hello and goodbye. In the next image, the man steps out of the train and onto a bustling platform. No one is there to meet him. We then follow the man out into the magical, unbearable life of the city. At first, he is merely a spectator. He witnesses petty crimes and stares into shop windows, goes to the museum and into the crowd. A woman passes him by and hands him a note — the man’s initiation begins. He falls in love, is exalted, and then is spurned, and falls into despair. He joins a political rally, leads a group of men on strike, and then becomes disillusioned by the endless discussion. He liberates a girl from the clutches of an abusive father, then watches her grow and die. He leaves the city, steps onto a ship, and travels the world. When he returns to the city, his idealism is stronger than ever, but it is marked by cynicism. He crashes the tables of the rich, drinks with the lonely and fights with them, moons a bishop. We watch the young man jump into the river to save a drowning woman, and when he is offered a medal, decline. In a scene that follows, the young man is back to his shenanigans, trying to put a top hat upon a statue of a cavalier. In his final commentary on city life, the young man stands on the tops of the buildings and ejects a powerful stream of urine down to the streets below. After farting into a crowd of aristocrats, the man is chased out of town. We follow his long walk to the countryside. The man shares an evening with a family there and bids the family farewell come morning. Outside, the man falls to his knees before a cross standing in a field. He stands small before a meadow of flowers, wanders into the forest, sits among the trees, lies before the tearful moon, and then dies. In the final scene of My Book of Hours, the skeletal spirit of our protagonist dances across the cosmos, waving a final goodbye.

A spread from My Book of Hours

•

In the 1930s, when the Nazis took power in Germany, Frans Masereel’s works were almost immediately given the “degenerate” label and banned. Masereel and his wife fled to London and then Paris. During the German occupation of France, they assumed false identities and lived in hiding, traveling from town to town until the war’s end. In 1949, Masereel settled in the old port in Nice, where he lived quietly until his death in 1972.

War, affirmed Thomas Mann, was the inspiration behind Masereel’s art. This is a funny observation to make about an artist who was a devout pacifist. Of himself, Masereel said, “If someone were to wish to sum up my work in a few words, he could say that it is dedicated to the tormented, directed against tormentors in all areas of social and spiritual life, it speaks out for the fraternity of humanity, turns against all whose aim is to set people at odds with each other or incite conflict, it is addressed to those who desire peace and despise warmongers.” Like many European artists of his generation, Frans Masereel was in physical exile. But he was, as a pacifist during two great wars, a spiritual exile. In refusing to take up arms, Frans Masereel spent much of his life watching.

Throughout his career, Masereel found himself in the curious position of re-creating scenes of war in which he did not actually fight. Although he was, as Mann said, very much influenced by war, the primary tension in Frans Masereel’s work is that of an artist caught between the roles of participant and observer. He is like Tu Fu or Baudelaire, artists on the fringes of society. How, asked Masereel, can one – should one – participate peacefully in a world that is, essentially, destroying itself? All throughout the book, the protagonist struggles to belong, to feel a part of the world. He loves, fights, travels, wanders, rescues. But when is he actually participating and when is he playing a part? It is only at the end, when the man is about to die, when he has stopped struggling, and is silent, that he seems to find real peace.

In his 1987 work Being Peace, the Buddhist Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh wrote that pure observation is an illusion. Even when we feel outside of life, we are always in it. Even modern physicists, he writes, no longer think the word ‘observer’ is valid. When they “get deeply into the world of subatomic particles, they see their mind in it. An electron is first of all your concept of the electron.” That said, the act of observing – of really seeing – can make us more awake to life. Paradoxically, when we consciously step back from life, we can often participate in it all the more fully.

If we want peace, then, we must dissolve the line between observer and participant, between peace and war. We can’t pretend war is not there, can’t pretend that peace will come just by “being peaceful.” We must be able, in a way, to be war without necessarily being in war. Baudelaire expressed like this: “I am both wound and knife.”

The urination page from My Book of Hours

There is a saying that has become a cliché: “Pictures speak louder than words”. But sometimes, a picture can speak louder than words because it contains a profound silence. It’s what a picture does not say that can often make it loud. What is, after all, a wordless novel but a novel devoted to the message of silence? Masereel’s wordless books were illuminated silence — the silence of exile, of wandering, of peace. Maybe one could think of it as the difference between intentional and unintentional silence. Unintentional silence is assent to an unacceptable situation; it is the silence of fear, the silence of perpetrators and of accessories. Intentional silence is the silence of the true participant; it is the silence being both knife and wound.

“I have the impression,” Thich Nhat Hanh recently wrote, “that many of us are afraid of silence.”

What are we so afraid of? We may feel an inner void, a sense of isolation, of sorrow, of restlessness. We may feel desolate and unloved. We may feel that we lack something important. Some of these feelings are very old and have been with us always, underneath all our doing and our thinking …But when there is silence, all these things present themselves clearly.

It is telling that the work of Europe’s preeminent silent novelist was admired by those counted among the greatest writers of the early 20th century: Mann, Hesse, Zweig, Rilke, Rolland, Brod. Some have said that Frans Masereel used the illuminated manuscript merely as a formal convention to convey a message that is primarily secular and political. I think this analysis misses the mark. Masereel created a book of hours because he was trying to express something more eternal than politics: The feeling of being an exile on Earth that spiritual seekers have been feeling for millennia. The wordless novel was a perfect medium for capturing the spiritual crisis Masereel and his contemporaries found themselves in, living in a post-Nietzsche, post-World War I Europe. Wordless novels were the voice of a generation struck dumb, a generation that could only point, and show, and emote. But this same generation was also seeking a way to express its silence.

“Incomprehensible ideas,” said Expressionist artist August Macke, “express themselves in comprehensible forms…”

“If everything were to perish,” Stefan Zweig once remarked of Masereel, “all the books, monuments, photographs and memoirs, and only the woodcuts that he has executed in ten years were spared, our whole present-day world could be reconstructed from them.”

At the beginning of Passionate Journey, Masereel included a line from Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass: “Behold! I do not give lectures, or a little charity: When I give, I give myself.”

•

The final page from My Book of Hours

Today, graphic novelists carry on the work of Frans Masereel. The “father” of graphic novels – Pulitzer Prize winner Art Spiegelman, author of Maus – has declared Masereel among his chief influences. In a presentation of Spiegelman’s new multimedia project Wordless! in Chicago last year, Spiegelman took on what he called the “battle between pictures and words.” “Wordless novels do have words,” he told his audience, “they just take place in your head.”

Picture stories ask us to make meaning out of abstractions, using both sides of our brain, and as you focus on and decode the images, you’re left with that holy-shit flash of recognition as the pictures take on meaning.

Wordless novels, Spiegelman was saying, are engaged silence. This kind of silence is extremely destabilizing. It scrambles your brain, makes demands on you. And yet the more you focus, the clearer the picture becomes. “Furnished with … art, purged by silence,” wrote Susan Sontag in “The Aesthetics of Silence,” “one might then be able to begin to transcend the frustrating selectivity of attention, with its inevitable distortions of experience.”

“Don’t worry if you get a little lost while you’re watching,” Spiegelman reassured his Wordless! audience. “I’m hoping you will careen between my words and these picture stories until you’re left as breathlessly unbalanced as I am.”