“No one ever heard of man canners when I was a girl,” said Sarah Tyson Rorer, who spent her lifetime teaching dietetics and cooking skills to young women — and, eventually, men. Whether married or single, men too wanted to make soap, buy groceries economically, and take part in other domestic duties. According to Rorer, the division of gender roles in the private sphere was changing: The modern technologies that made it easier and more efficient to cook at home essentially despecialized household labor. With the increase of both single-person households and dual-income marriages, men and women alike needed to sharpen their knife skills. For Rorer, this is a highly desirable outcome. When domestic work is shared and when women are encouraged to have interests outside the home, she notes, they make better companions to their husbands.

This interview sounds almost as if it could have been excerpted from a contemporary trend piece in a major publication covering the rise of male food bloggers or bearded Brooklynite soap makers — at least, it could pass for modern if Rorer weren’t so positive about change. (Today’s contemporary cover stories tend to bait controversy by wringing their hands over the doom of marriage and romance if men and women challenge gender norms.) I could also see this optimistic observation fitting into an upbeat magazine in the 1970s, a period of high inflation and low economic growth which inspired a groovy DIY attitude in men and women alike.

But in fact, Sarah Tyson Rorer — who started the Philadelphia School of Cookery in 1884 — gave her interview to a New York Times reporter in 1925. The economy was doing well; there was plenty of work to be had in the businesses and factories that accompanied the post-WWI boom in entertainment, technology, and communications. The workforce was flooded by single men and women who left the domestic shelter of their family homes, moved to urban centers and rented rooms, pursuing careers and educations before starting their own families. We remember this era as the Roaring Twenties or the Jazz Age, but it was also a great era of civic change: Women in particular formed political organizations in droves, spearheading education and public health reforms. Sarah Tyson Rorer herself played a central role in the development of what she would have called “domestic science” — for Rorer and her colleagues, a clean kitchen and a healthy diet were teachable scientific skills, and vital to the prosperity and wellbeing of an increasingly modernized America. Domesticity may have a historically feminine association, but the new technologies of the 20th century did not yet have a gender, so despite Rorer’s surprise, hers was not the only school to teach domestic skills to young men. (She calls them “new men,” in the manner that nearly everything in that period was called “new.”) Besides, despite all the technological leaps, the singletons of the 1920s didn’t have all the conveniences (home refrigerators, take-out) we do now; the smart young bachelor still needed to know how to buy good milk and preserve perishables.

It’s tempting for those of us in the 21st century to think of the past as a straight line, whether we see the line as a march toward progress or a road leading to where roads paved with good intentions proverbially lead. In our decade, as full of technological wonder as the early 20th century while just as economically shaky as the 1970s, we want to write our relationships to food as something special and particular to our time and place. When a man cans — or makes soap, or stays at home — it’s still unusual enough to draw notice, but we also want to cast it as something new, or at least as the culmination of years of feminism and pushing back at gender norms. When men and women take up old crafts — preserving, knitting, growing edible plants and urban farming — there’s a sense of reclaiming something lost to time, reversing the timeline to a pre-industrial, pre-corporatocracy era.

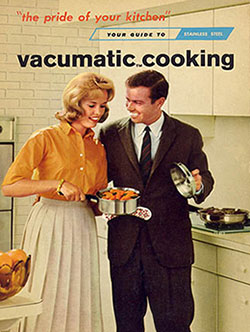

But in truth, history is not so linear (if not quite cyclical, either) and predecessors circled from nostalgia to modern-mania and back again just as we do. The pre-feminist era so lauded by home-cooking advocates like Michael Pollan was itself a creation of nostalgia: After decades of Progressive-Era women’s committees, the necessity of women’s labor outside the home during the Depression and WW2, and the leadership roles of women in education and public service, it was necessary to look all the way back to the 19th century to reclaim the importance of a woman’s role in the home. At the same time, the language of midcentury housewifery borrowed a great deal from Rorer-esque domestic science — likened to operating a factory or a business, housewifery was treated in magazines and papers as an occupation, something that did indeed need specialized know-how. At least, the know-how of a factory operator: Many midcentury housewives did not know how to bake their own bread or can their own tomatoes, unless they picked up these skills as a hobby; their job was Chief Purchaser for the household goods, responsible for choosing machines and groceries that kept the household running while leaving her enough time to (as Rorer said decades earlier) be better companions to their husbands.

People want to look toward the past when they are afraid of the future, but a misremembered-but-comforting past tends to conceal even more comforting facts: That people have always ingeniously survived economic downturns and traumatic wars. That despite the incredibly ancient histories of the industrialization of food, and corporatization, neither has managed to destroy home cooking or even the home. That canning classes are almost a century old, and apparently have always been available to all genders without destroying masculinity or marriage or anything like that. And remember that when you break out your vintage pots and reclaim your lost domestic arts, you’re practicing the oldest art humanity knows — adapting for the future. • 30 August 2013