This is the first story in a package celebrating all-things Oscars, republished from The Smart Set archives.

Entering the dazzling world of Hollywood’s glittering extravaganza, ‘Tis the Oscar Season’ is a whimsical journey through the pomp and circumstance of the Academy Awards. From the opulent red-carpet spectacles to the meticulously crafted speeches and the delightful unpredictability of award winners, writer Dr. Melinda Lewis captures the essence of Oscar fever. With a playful tone and keen observations, it explores the cultural significance of this annual event, blending humor with insightful commentary. We’ll follow this essay with two other pieces from the vault that explore Hollywood’s most glamorous night.

This story originally ran in February 2019.

As we all gear up for the 2020 Presidential race with candidates from the left volunteering themselves as tributes, we have also hit my favorite time of the year every year: Oscar season. This particular ceremony gets lumped into a lot of conversations about taste and value, which considering the show’s raison d’etre prove futile and often boring. An attempt in the 1930s to rebrand and reinvigorate Hollywood during the 1930s, The Oscars were born as a means to entice people back to the movies. The audience might not have been super interested in a film, but a prize winner or a prestige picture, might gain some interest. The awards were and continue to be a smoke screen.

But I love them. I loved them as a kid. Growing up overseas on military bases, they started late on Sunday night, too late for me to stay up on a school night. This lead to a lot of bemoaning on my part to my mother about the injustices of the world – of the Super Bowl being accessible (I can’t remember if it was live or not), but being unable to view the Awards as they happened. Some might call me an advocate and a hero, but I was just a deeply passionate fan of film. I didn’t know what The Crying Game was, but I wanted to be involved regardless. As I grew up and began actually watching more, I became even more obsessive. I screamed at the television when I thought the incorrect choice was made. I was overwhelmed when the person I wanted to win, won. It was as if we triumphed together.

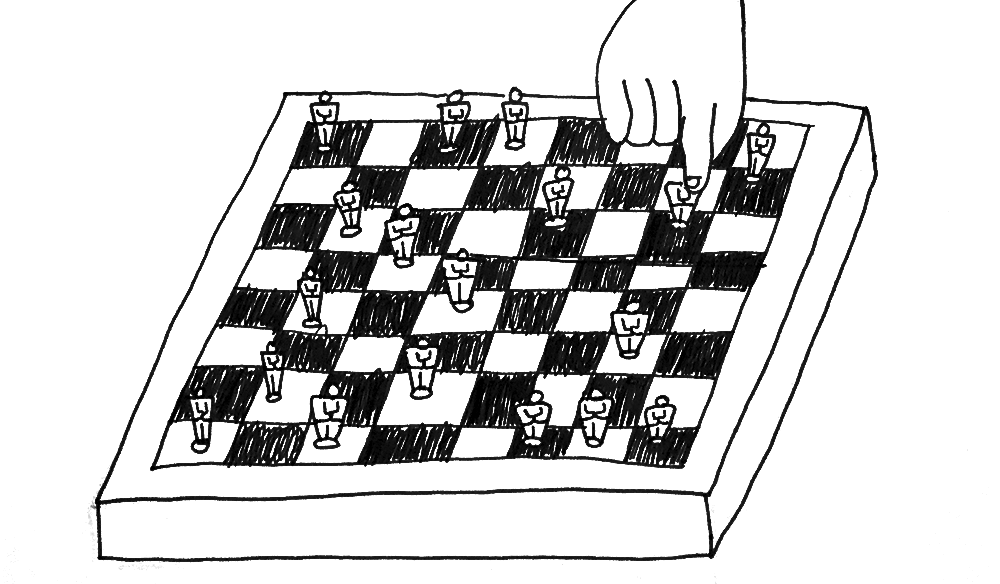

It was in college that I began to recognize that perhaps the Awards weren’t simply based on meritocracy. There were issues of taste, Hollywood traditions and plotlines, and pure boots on the ground campaigning. A collection of producers, agents, and publicists gathering in, what I imagine to be, a war room, trading names and rearranging placeholder to figure out who has better chances in different categories, and in what ways they can best support and amplify their candidate. Essentially, I imagine an agent rehashing James Carville’s infamous speech from D.A. Pennebaker’s The War Room about the ’92 presidential election the day before each ceremony to a roomful of media analysts, and strategists, and publicists:

There’s a simple doctrine: outside of a person’s love, the most sacred thing that they can give is their labor. And somehow or another along the way, we tend to forget that. Labor is a very precious thing that you have. Anytime that you can combine labor with love, you’ve made a good merger. I think that we’re gonna win tomorrow . . .

It really takes a village to make an Academy Award winner.

In 2015, The Hollywood Reporter began running their column “Brutally Honest Ballot,” which highlights the opinions of several Academy voters leading up to that ceremony. What is striking is not necessarily their choices, but the rationale, which consists mostly of instances that rubbed them the wrong way, likability, or confusion. When evaluating the Best Actress category in 2014, one voter declared

I didn’t vote for Jennifer Lawrence, even though I thought she was very entertaining in the movie, because (a) she just won last year, and (b) we can’t give everything to Jennifer Lawrence when she’s 22 years old because Jennifer Lawrence will be institutionalized. She will have gotten too much, too soon, too early, and she’ll lose her mind. I also didn’t think she gave the better performance.

Another anonymous voter in 2017 talking about the Best Director race:

Damien [Chazelle] is such a sweetheart; I loved what he did with Whiplash and this one, and he’s probably going to win. But I voted for [Kenneth] Lonergan, because it was harder to make everything click on that movie, and he really succeeded.

Like any other type of campaign, the personal becomes intertwined with techniques and ability, and the overall politics of the industry at the time of voting. Everything becomes possible when we rid ourselves of this idea that what is being evaluated for quality. Instead, we have a world of potential and aspiration. We have studios, producers, and above the liners jockeying for position. There will be dinners, a surge of well-poised interviews, and avoidance dances regarding scandals that could be detrimental to a film’s chances.

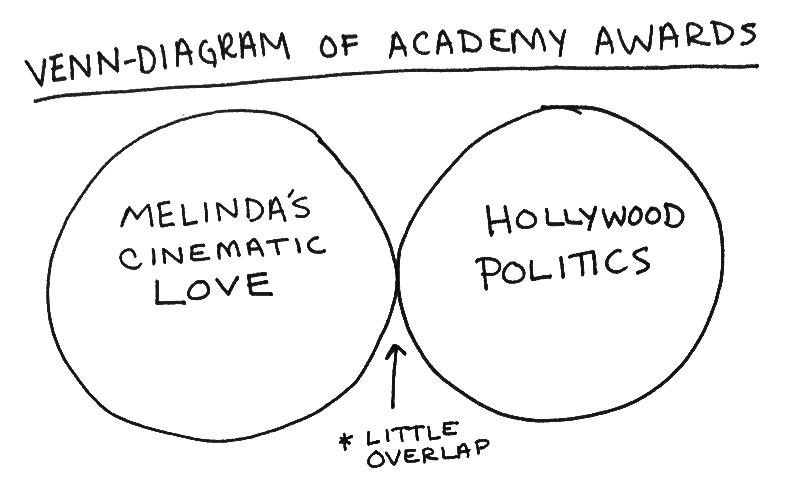

It would seem as if the machinations should deter from a movie lover’s adoration of the ceremony. So often, we hear the cynicism of those who discount the awards for not recognizing their favorites or giving the films the wrong awards or for pandering. All kind of true. But instead of assuming that the Awards will somehow magically conform to my taste, I’ve just begun to let go and enjoy the process of the entire thing. I’ve compartmentalized my cinematic love and Hollywood’s politics, which rarely meet in the middle of my personal Venn diagram. For the next month, however, I’m stashing my unabashed love for Olivia Coleman and paying attention to the media’s All about Eve approach to Glenn Close and Lady Gaga. I’m going to enjoy the leaks of onset indiscretions or the postured monologues about the difficulties working on an emotionally complicated set like Bohemian Rhapsody. And I’m even going to embrace all the well rehearsed speeches about the honor to even be participating in such an honorable ceremony.

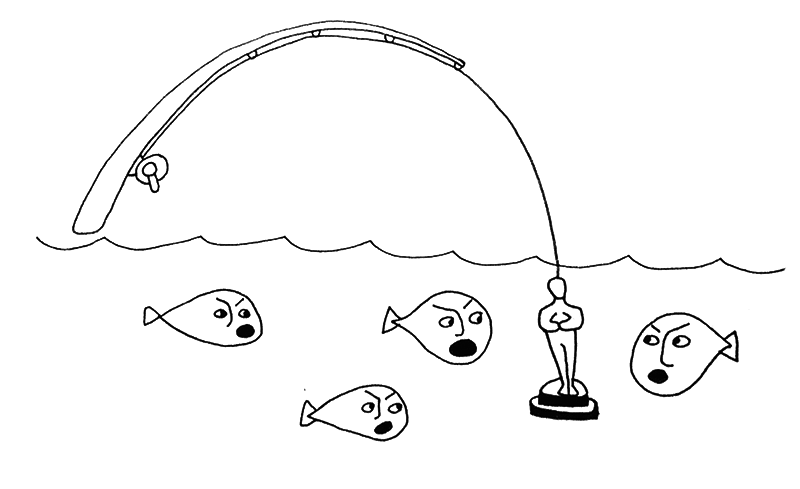

My favorite example of a beautiful campaign was DiCaprio’s run for Best Actor in 2016. Nominated five times previously for What’s Eating Gilbert Grape, The Aviator, Blood Diamond, The Wolf of Wall Street, he had done pretty much all the things an actor needs to do for an Oscar. He paired with the best filmmakers. Played villains and heroes. Donned accents. Gained and lost weight. But he was the victim of poor timing. Then came The Revenant. The film already had a firm foundation – Alejandro G. Iñárritu was already an Oscar powerhouse, winning Best Director for his film, Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance). The majority of the film left DiCaprio alone most of the time, allowing him to really chew on all the scenery and have nobody come close to outshining his performance (somebody like the formidable Tom Hardy). While DiCaprio does media to support his films, this award season he seemed to be all in, in comparison to previous years – much more was said about the vegetarian eating raw meat, the hardship he faced in the cold, and the lack of glamor to the role. He wasn’t just talking about the movie and his performance, he was really unpacking the labor of his performance. He was demonstrating that this wasn’t just a role, but a lived experience, one in which (threatening or not) he deserved to be recognized for. And everybody else on the project affirmed this, as in their own interviews, they would speak to DiCaprio’s incredible performance, willingness to go above and beyond in his performance. In other words, he worked his ass off, give him the award already.

And that was the year he won. The media constantly reminded us that he had yet to win, despite being one of the biggest superstars in Hollywood and the world. We were reminded of his more than 20 years in the industry, his other great works that demonstrated he was more than just a heartthrob but a bonafide actor, and that it was his time. Regardless of whether it should have been for The Revenant or Gilbert Grape, the audience in the auditorium gave him a standing ovation, an actor finally getting his after all these years (another narrative Hollywood loves to perpetuate). He performed a phenomenal monologue as his speech, clearly rehearsed, incredibly cogent, and forgetting nobody we need to hear in an acceptance speech: colleagues (by name), team, parents, friends, and the environment. He skipped up the stairs with a strong suspicion he’d win, because he had done everything Hollywood asked. His love and labor prevailed.

If we learned anything from the La La Land/Moonlight debacle, it’s that there is a lot that could happen in these campaigning seasons. Despite the conversation regarding Best Actor might be pinpointing Rami Malek or Christian Bale now, we can’t count out a Bradley Cooper power move or a Willem Dafoe sneak, no matter how unlikely. It has happened before. As audience members we patiently waited for Almost Famous’s Kate Hudson to pick up her award after a season of the press and industry strongarming to suggest that she would definitely win only to find ourselves agape when Marcia Gay Harden walked up an accepted the award for Pollock instead. Or the moment on the tape when Michael Keaton graciously put away his speech as Eddie Redmayne’s name was called instead of his. Entertainment Weekly reporter Steve Daly dissects the strategy used for Harden’s win, declaring Sony’s re-release of the film in December helped remind people of its existence and reducing her role from Best Actress to Supporting Actress helped highlight her performance. Keaton explained his loss on The Late Show with David Letterman, with an anecdote from one of the many Oscar luncheons wherein a Hollywood insider expressed “Illness always wins.”

Hollywood loves a narrative to provide with each award. They love a physical transformation (weight gained, prosthetics, fake teeth). They love a comeback narrative (like Keaton’s). They love an ingénue. They love a vaguely political film. They love reflections on identity (within reason). And have a problematic obsession with disability (as illustrated in Keaton’s anecdote). They also adore a person who is both humble but clearly wants the Award.

There are also the ways in which the Academy rewards movies they liked, but not enough. Best Writing, for example, always seems to be given to a well regarded film, but one too soft on its Academy tropes to be Best Picture. Sofia Coppola and Jordan Peele can be acknowledged for films that really provided a lot for audiences to chew on and be excited about, but not ones that the Academy feels strongly about – or know enough that these are films that should be rewarded something, but not anything as prestigious as Picture or Direction. We can also consider the apologetic award given for a film all too late. Should Martin Scorsese, who has had an incredible impact on the way American films look and feel, should have been rewarded before The Departed? Probably yes. Was Al Pacino’s award Scent of a Woman kind of weird? A little. But sometimes the Academy likes a mea culpa and provides an award for a body of work as opposed to a singular performance – a “whoopsie” award.

While for the most part, there are a few surprises on the day, enjoying the process of putting together a win, is akin to the plays used in the Super Bowl. It has become suspiciously like the political trails, where it is less about policy and more about who we’d rather have a beer with. It’s the spectacle and machinations over the substance of each film – the power of schmoozery, PACS, and campaign strategy itself over the actual quality of the content campaigned.

And we have some fun things to watch this season. Glenn Close and Lady Gaga trying to overly humble themselves over the Best Actress prize (which should go Olivia Coleman anyway, every year, for as long as she wants). Bohemian Rhapsody producers no doubt sidestepping every mention of Bryan Singer thrown their way, and the coin toss of the Best Actor and Actress categories. Maybe we’ll get more Director’s Guild drama with Bradley Cooper winning one of his DGA awards, providing a boost to Gaga and A Star is Born. There are so exciting possibilities.

As much as I am cynical about this whole Hollywood idea of meritocracy, 9-year-old channeled her energy into finding the joy elsewhere, not in the estimation of quality and nuance of taste, but in the strategy and party dips. The Oscars simultaneously don’t matter and are incredibly important. The publicity machines that surround their campaigns have become incorporated into our politics. The prize itself will be used to jettison movies for as long as the awards exist if not longer. The awards will boost an ingénue to become a full fledged power player. I’m genuinely excited for the individuals who win because they have legitimately worked very hard to gain entry in a notoriously difficult industry, have played the necessary games to achieve even just modicum of success (let alone entry into the echelon of people able to access such awards), and have smiled and nodded through the gauntlet of necessary luncheons and media appearances to demonstrate their worth and value. It may not be the work we expect to be accounted for, but love and labor nonetheless. And while we might not need to debate whether the award winners are the right ones or the wrong ones (since that doesn’t necessarily matter), we can at least find a modicum of satisfaction in these Hollywood games. •

All illustrations by Isabella Akhtarshenas.