The lion, hunched in place, let loose a guttural bellow unlike anything I’d ever heard. “What was that?” I asked the nearby volunteer. “A lion’s roar,” he said. “That’s a lion’s roar?” I replied, incredulous. He held up a hand, said, “Listen.” From across the sanctuary, out of view, the young lion’s mother answered — again, that same peculiar, heaving rasp, more of a retch than a roar. “Not what you’d expect, right?” the volunteer said and grinned. He added, “That’s because the roar you’ve always heard on TV and in the movies — the famous MGM lion — that’s a tiger’s roar dubbed over to make the lion sound scary. Because the real sound a lion makes is pretty strange, isn’t it?”

We stood in silence and listened. My scalp tingled — not from fear, but awe that swelled from ribs to fingertips. Something snapped awake in my consciousness, too, an instinctual, if long dormant, awareness of nearby predators. Back and forth the two creatures bellowed to one another, their eerie communication lost upon us.

My partner, Mark, and I were visiting Catty Shack Ranch and Wildlife Sanctuary in Jacksonville, Florida, on a chilly winter’s day. This was among the last in a long list of such nonprofit organizations we’d set out to visit on the bucket list I’d made for 2017. The mood among many in our circles was grim. With so much falling apart in the world — politically, economically, and most frightening of all, ecologically — what kind of meaningful action could any individual take? One day, after I had read about the Great Barrier Reef in its death throes, I wept, a pit of rage and grief in my stomach, haunted every time I looked up at the framed photos of my travels throughout Australia 20 years ago. What have we done? A yearning welled up within me: to be closer to nature, to look our fellow creatures in the eye, and plead to Forgive us for we know not.

What we could do, I decided, was to visit and support the wildlife sanctuaries and refuges in our state, where some people were carrying out meaningful and important work. There, we might bear witness to the magnificence of such animals while we still had the chance, and our nominal entry fees would make the most direct impact.

But first, I needed to be sure that we would be visiting rescues that give their animals complete sanctuary, and don’t exploit them for other purposes. This was before Tiger King, the popular documentary series which aired this past spring, yet my fleeting, scant observations of roadside attractions and zoos had been enough to send a clear signal that any such human-run wildlife park must be seriously vetted. As I researched the many (and there are many) wildlife sanctuaries and refuges throughout Florida, I was dismayed to find some places listed by travel bloggers and writers that raised red flags. Among the most concerning and egregious that stood out was the Wild Things zoo in Dade City, Florida, ordered in March of 2017 to stop allowing tourists to swim with tiger cubs, following a lawsuit filed by the USDA citing Animal Welfare Act violations. A far slicker operation was the Big Cat Habitat and Gulf Coast Sanctuary in Sarasota; the organization’s well-designed website almost had me fooled, my finger hovering over the “Buy Tickets Now” button. A slower, more scrutinizing scroll through their gallery revealed photos, here and there, of big cats performing circus-like tricks, and this, again, raised alarm bells. Sure enough, follow-up research unearthed numerous USDA violations by owners Kay and Clay Rosaire. Although they market their nonprofit as a “sanctuary” and “educational,” the Rosaires operate under numerous licenses and aliases, and their facilities are unaccredited. For those who don’t want their dollars going to parks that operate as more of a circus or attraction rather than a rescue or rehab facility, some due diligence before you hit the road pays off.

Which wildlife rescues near me offered their animals true sanctuary? Carson Springs of Gainesville, Catty Shack Ranch of Jacksonville, the Busch Wildlife Sanctuary in Jupiter, and Homosassa Springs State Park don’t require any tricks or demonstrations from their feline residents, nor does Big Cat Rescue of Tampa. The latter was subsequently featured on Tiger King, and while many may consider the owner, Carole Baskin to be eccentric, the organization checks out as the world’s most accredited rescue facility for exotic cats — as far as one could tell. Homework complete, I made our road trip list.

I remember the moment when, through a patchwork of lush greenery, the tiger appeared, partly hidden among the leaves. He blinked, and I caught my breath — as close to the experience as viewing one in the wild as I would likely ever get. The morning was already 90 degrees, and he was lying on the bank above the water — Big Cat Rescue provides some large pools where its tigers may swim. This was the first time I ever sensed myself as potential prey. The feeling bristles on a cellular level, primal and ancient, and shocking when one has lived her entire life as a modern, city-dwelling human. At this rescue and others, much of the big cats’ behavior evoked that of their smaller domesticated relations — I laughed when, at the rattle of the food cart, a tiger would jump up from napping and begin to pace exactly as our grey cat does at home at dinnertime. So, too, the big cats enthusiastically gnaw and paw their “enrichment” balls.

Others would stalk us. At Carson Springs outside Gainesville, the panthers and Siberian lynx fixed their gazes upon the weakest of those who’d gathered to listen to the keeper talk: the toddler clutching her mother’s knee, the elderly man limping to catch up. A poignant reminder that none of these glorious creatures are pets.

And yet many of these animals were there, given homes at rescues, precisely because certain arrogant humans had tried to make them just that — to tame and “own” what belongs in the wild. At each enclosure, we heard a grueling story of how each animal came to be a resident: story after story of roadside petting zoos, of filthy cages, of private collectors. Of the latter, a few owners had been well-meaning and adequately funded, but upon their deaths, the deceased inevitably left ill-prepared heirs scrambling to find facilities able to take an African lion or Siberian tiger. Bobcats, lynx, and servals are often sought out as pets because of their smaller size; servals, especially, are given up once they attack ceiling fans, which appear too much like birds for the servals to tell the difference. It shouldn’t take a genius to glean that wild cats such as these will quickly destroy a house — apparently, this obvious outcome doesn’t occur to the status-seekers who desire such a “pet.” With each story, my gut clenched; sometimes, hot tears pricked my eyes. “I can’t listen anymore,” Mark said more than once and sought out a bench.

These places shouldn’t exist, we’ve repeatedly said to each other, back in the car. But they’re faced with attempting to clean up the enormous messes left by other humans, those who act out of blind ego, arrogance, and selfishness. Many of these animals were born into captivity and stand no chance if released into the wild, so living out the remainder of their years at a true sanctuary or rescue is the best possible option for them. I wondered as we pulled away and back into the urban sprawl, just how many people in the surrounding neighborhoods realized that dozens of big cats live next door? The cages can withstand hurricanes, but what if a greater calamity or collapse occurs? Until my year of visiting sanctuaries, I was wholly unaware of how many exotic animals live among us — there are some 5,000 tigers alone in captivity in the United States.

Perhaps what we were unsettled by the most, however, was our fellow humans’ behavior on the tours. “Oh, don’t you just want to cuddle him?” and various other gushing statements were uttered more than a few times by the visitors next to us; despite the clear endeavors by the tour guides to educate, one could see how for some admirers, given the chance, they, too, would swiftly make a “pet” out of a beautiful tiger. Absent of staff vigilance, clearly articulated instructions, and posted warning signs were often flagrantly ignored. At the smaller, less well-funded, and thinly staffed Busch Sanctuary in Jupiter, we entered an area where three sleek and stunning Florida panthers were kept, one of which was being rehabilitated for release. A family entered with a handful of children about eight to ten years old — old enough to know better — who began racing back and forth before the cages. Immediately, the panther locked upon the darting kids as prey, and gave chase, the kids’ squealing and laughing, and the parents saying nothing, despite the signs warning not to “run, jump, or otherwise agitate the animals.” I bit my tongue, because who wants to be the childfree adult stranger who steps in and disciplines somebody else’s kids? Had the children showed up unchaperoned, I would have. This was a scene that repeated at Catty Shack, a facility that also appeared lacking in volunteers and thus left open the opportunity for such shenanigans (Big Cat Rescue and Carson Springs appeared to have adequate staff to closely monitor the tour groups).

The sight of a perturbed panther or tiger frothing at the mouth with its gaze locked upon one’s children should be alarming enough for the adult in charge to step in, one would think. Never mind that what is a game to children not only agitates the wildlife residents, but reinforces the imprint that humans, and especially children, are prey. For a native specimen soon to find itself released — as was intended for the Florida panther recovering at the Jupiter facility — such an imprint could prove especially dangerous, should the animal encounter people again.

Sadly, we witnessed far more parents laughing, merely entertained by these antics, or too busy taking selfies and posting to social media to intervene. For many visitors — and this is what was most disturbing since we had deliberately chosen to support refuges and sanctuaries, not circuses or zoos — the animals, even rescued ones, existed for human entertainment. There was a brazen lack of respect among visitors, borne from a complete detachment from nature, that was unnerving to observe at facility after facility, again and again.

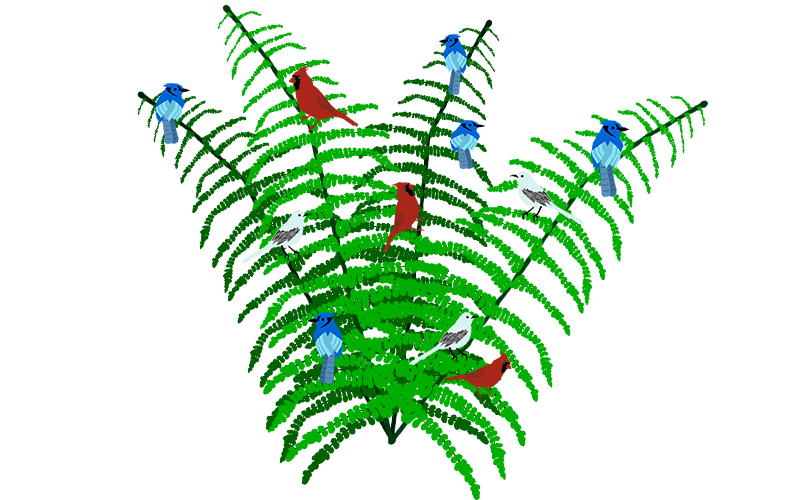

The off-putting behavior of our fellow homo sapiens, however, wasn’t enough to keep us from venturing forth to observe these magnificent species, both exotic and native, that are so quickly dwindling in number—going extinct at one thousand times the background rate. On that same day at the Busch Sanctuary, Mark and I came upon the bird enclosures. I marveled at a pretty pair with blue and white markings, and exclaimed, “What are those? I don’t think I’ve ever seen that bird before.”

“Those? Blue jays, they’re common,” he replied. “They were everywhere when I was a kid on the Space Coast. The trees were loaded with them — and cardinals, mockingbirds.” A long pause. “Actually, I haven’t seen blue jays in a long time,” he said, slowly. Beneath his silver hair, his face clouded.

“They look like exotic birds to me,” I said. I’m 20 years his junior. “I don’t recall seeing them around.”

We walked on, quietly, and let the sobering reality sink in.

“The blue jays bring their young to the feed-basket and the bird-bath for a week or two in the spring,” Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings writes in her 1942 essay collection, Cross Creek, of her rural homestead in north-central Florida. “Ordinarily the jays are almost as sociable as the mocking-birds and like to live near people and houses. They drive off other birds and many bird-lovers have difficulty in keeping them away in order to have the song-birds about.” The Pulitzer Prize-winning author’s homestead, now the Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Historic State Park, is located outside Gainesville and Ocala. Although the birds might not be there in the numbers they once were, the spot is still a lovely one to visit.

At Homosassa Springs State Park, a few of the last remaining red wolves pant and loll beneath the trees; wolves once populated the East Coast, including Florida, and are mentioned numerous times in the accounts of 18th century naturalist and writer, William Bartram. In his Travels, Bartram writes of Georgia and Florida, “The buffalo, once so very numerous, is not at this day to be seen in this part of the country; there are but few Elks, and those only in the Appalachian Mountains.” Over-hunting and loss of habitat resulted in their demise, and the last elk in North Carolina is believed to have been killed in the late 1700s.

In the last 200 years, our lives have blindly accelerated at an astounding speed, and we have set about exchanging natural wonders for man-made ones: skyscrapers, airplanes, cruise liners. Faster than expected, the headlines keep coming.

One of our final pilgrimages was to the Audubon Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary in Naples, where the last significant stand of old-growth cypresses remains. Many do not realize — I had no idea — that vast forests of live oak once covered Florida’s East Coast, nearly all cut down for naval ships by the 1800s. The ancient cypresses, related to the giant redwoods, were logged almost completely throughout south Florida until the timber industry’s eventual collapse by the mid-twentieth century. Along the two-and-a-half-mile stretch of boardwalk that winds through Corkscrew Swamp, quietude and an air of holy reverence may be found, the carefully preserved habitat a brief trip back in time, to Bartram’s undisturbed Florida, one that must have resembled the Moon of Endor.

Only now do I see, after our year of regional travels, that we don’t even realize how much we have lost.

And yet there is no place I would rather be, in this season of poignant grief and anger, than among our incredible fellow species. In visiting such places, I have learned that there will always be both moments of magnificence along with maddening frustration. I recall the woman who, getting out of the car next to ours one day at the Everglades National Park, was loudly complaining to her husband, “Why did we come here? I’m telling you, there’s absolutely nothing to see here — nothing!”

Not an hour earlier, we had taken a side route from Big Cypress National Preserve through the wilderness to Shark Valley. For miles, flocks of brilliant white herons and egrets took flight before us, peeling off in a breathtaking, continuous V pattern — their future, and ours, uncertain. •