I came across a surprising claim the other day. Shortly after reading that in the last 200 years, Australia has suffered the largest documented decline in biodiversity of any continent, I read that my home state’s habitat has remained “relatively unchanged” since 1936.

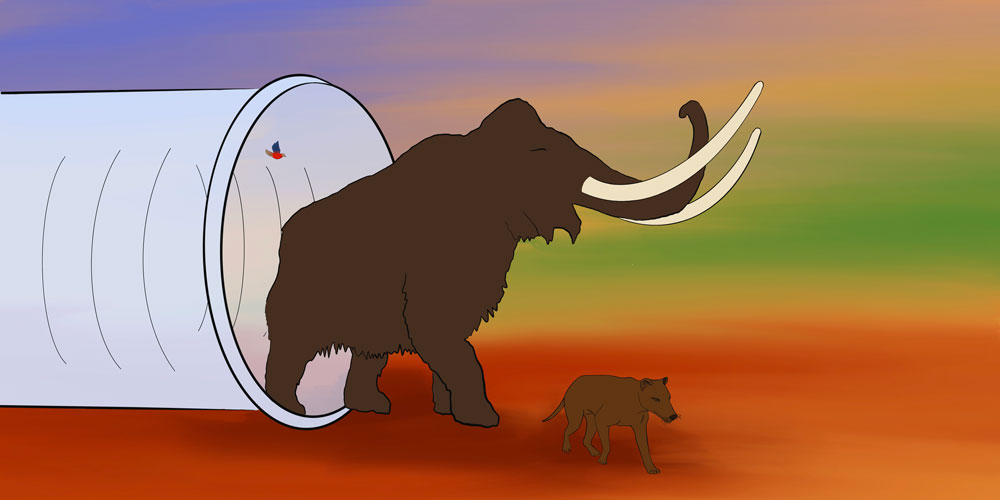

The quote was on a US biotech company’s website. Last year the company, Colossal, which is trying to “de-extinct” the woolly mammoth, joined forces with a team of scientists at Melbourne University who are trying to bring back the thylacine.

The last known thylacine died in captivity in 1936 but according to Colossal’s website, “the habitat in Tasmania has remained relatively unchanged, providing the perfect environment to re-introduce the thylacine and enabling it to reoccupy its niche.”

I’ve lived in Tasmania for most of my life, and this was news to me. Perhaps some patches of Tasmania’s wilderness are “relatively unchanged,” but relative to what? Either way, it seemed a simplistic, optimistic claim; more the stuff of marketing than fact.

There was a time I would have been less skeptical about the habitat claim and more skeptical about the thought we could resurrect an extinct animal. But in the last 30 years, I’ve seen so much science fiction become fact, that I’m becoming less inclined to doubt what science and technology can do.

While I’m less inclined to doubt the could claims, I’m increasingly doubtful about the should claims — some go so far as to suggest that where we drove a creature to extinction, it’s amoral not to bring it back.

The interview that led me to Colossal’s website contained precisely this suggestion. The scientist in the spotlight was one very thrilled Andrew Pask. Pask, the professor who’s heading up work on the thylacine in Australia, said he considers himself the luckiest scientist in the country.

In 2022, a private donor offered his team five million dollars towards the project; this was closely followed by the unexpected offer of ten million dollars from Colossal. Now Pask is confident the project has the means required to succeed, and says he pinches himself “every single day.”

As for the ethics of it all, he happily reports that the thylacine gets all the necessary moral “ticks” for resurrecting a species. Because human beings deliberately wiped them out, Pask frames his project as a means of righting an injustice: we “owe” this to the thylacine.

I was troubled by this claim, I was also troubled by the way Pask spoke of technologies that might be developed along the way — the ability to grow embryos outside the womb, to produce livestock to feed the world’s expanding population — as if they weren’t problematic, as if their merits were a given.

He framed de-extinction as an act of conservation and seemed unperturbed by the fact Colossal has already started paying social media influencers to get the public on its side.

I had the strange sensation, as I explored Colossal’s website, of fiction blurring with reality. The website could have been lifted straight out of a book or film. The company’s name — such a generic, cartoonish, big-tech name — and use of “futuristic” fonts certainly didn’t help. Colossal. It’s exactly the kind of badass name I might have dreamt up when writing sci-fi in year four.

And then there were its claims. The website speaks of determination to “reverse the problem humans created” by following “the path to de-extinction,” then using the resulting creatures for “rewilding” so the planet can “begin to heal.”

It lists successive statistics about species loss — the rate of extinction in 2021 was “10,000 times faster because of human activity,” for example — to paint a dire picture, then boldly declares that more (and more elaborate) human interference — “de-extinction” — is “the” solution.

I suppose our take on this solution depends on our take on the problem. If humans caring more about immediate gratification than future generations is the problem, I’d say engineering replacement species while existing ones continue to die out would only prove we’ve learned nothing from our past mistakes and are willing to risk far greater ones.

Colossal says its “landmark de-extinction project” will be the resurrection of the Woolly Mammoth — or, more precisely, “a cold-resistant elephant with all of the core biological traits of the Woolly Mammoth” — that lived 4,000 “short” years ago. “Bringing the woolly mammoth back,” it claims, “means bringing back a better earth.”

I don’t doubt that some of the scientists that work for Colossal genuinely believe these claims. But I can’t help but doubt their faith is justified, in particular, their faith in humans and a human company. We might be smart, but are we wise? Can we really trust ourselves, when playing God, to do more good than harm? Our track record suggests not.

It’s a shame that we tend to silo different disciplines and fields of expertise — science, philosophy, ethics, literature, religion, history — thus missing opportunities for them to more robustly and authentically inform and challenge each other.

The more we isolate science and technology from the humanities the easier it is to disregard what we know of the human condition — our messy limitations and mixed motives, how easily corruptible we are — while eagerly, even recklessly, pursuing “progress” (and profit).

Even works of fiction contain truth — about human ambition and foolhardiness, about things not ever quite going to plan — that we’d do well to heed. And then there are the works of non-fiction.

Professor Ben Minteer, author of The Fall of the Wild: Extinction, De-Extinction, and the Ethics of Conservation says there’s a sense in which de-extinction as a “fix” elides “hard questions and deeper lessons,” which are rooted in the environmental values and lifestyles that have caused whole species to die out.

Minteer, who calls for “an ethic of collective self-control and ecological restraint,” wonders whether we’ll be able to maintain respect for “a wild nature” if we are increasingly manipulating, controlling, and re-creating it.

True power, he suggests, “resides not in greater control of nature, but in acts of forbearance.”

Forbearance and restraint sound a lot less thrilling than striving to go higher, faster, and farther than man has ever gone, but preventing species loss strikes me as a far nobler, less risky, more sophisticated, and more rational goal than mass-producing replacements.

But perhaps I’m being simplistic. Professor Beth Shapiro, the author of Life as We Made It: How 50,000 Years of Human Innovation Refined — and Redefined — Nature, notes that humans have always been “meddling” with their surroundings, and says that if we want to live on a planet that is both biodiverse and filled with humans, “we have no choice but to learn how to meddle even better.”

She may well have a point. But where should we draw the line? And who gets to draw it? Shapiro says it shouldn’t be up to scientists alone.

“We can’t, as Western scientists, make decisions for everyone in the world that are clearly going to impact their communities and their ecosystems. And so, it’s really important that these conversations are had right now, before the technology is actually possible, before we can do this well.”

I can’t help but wonder if the people behind Colossal have already made up their minds. I can’t help but suspect an “ask for forgiveness, not permission” approach. Judging by their website, they already have some pretty firm ideas about the kind of story they want to tell, and who the hero is.

“Human enterprise is responsible for many amazing developments. But many of them came at a cost to our planet and the natural resources the planet has provided for countless millennia. Colossal is leading the charge to restore what has been lost or is at risk of being lost.”

This is the kind of hubris we might expect from a company that considers itself more than capable of turning fiction into fact. But to expect a happy ending where everybody wins doesn’t sound like science fiction, it sounds like fantasy.

I think of Andrew Pask, waking up each morning, pinching himself, getting to work. This is a real man in the real world, but I can’t help but think of him as a fictional protagonist — well-meaning, but naive. I’m starting to feel like a fictional character myself, one I might have dreamed up in primary school — a cross between April O’Neil in the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and Lois Lane in Superman — a journalist who sticks her nose in where it’s not wanted.

Forget the fact that I’m not an “investigative reporter.” Forget that all I’ve done is listen to an interview, skim a few articles, and speculate. Forget the fact the only place I’ve “snooped around” is a public website. Forget the fact I’m writing this from my kitchen table on a bright Wednesday morning in a house full of people — forget the facts.

Let’s pretend it’s late at night, that I’m all alone, that I just had a shot of whisky to steel my nerves. Let’s pretend that as I finish this article and click “send,” ominous music starts to swell.

The camera’s zooming out now, you’re looking inside from the outside of my house. You see a hunched figure at a poorly-lit desk, straightening, stretching, turning off a lamp.

What happens next? I suppose it will depend on the director, the genre, and the script. What’s plausible? What’s possible? What’s not? Who, these days, can even tell?•