I hoped my daughter wouldn’t be detained by the immigration officials. I hadn’t seen her in a long time and I wasn’t sure what was happening. Finally, she emerged in her tattered jeans and sweatshirt and called to me from down the hall, “Hey Mom, I made it through.” I felt myself exhale deeply, physically relieved.

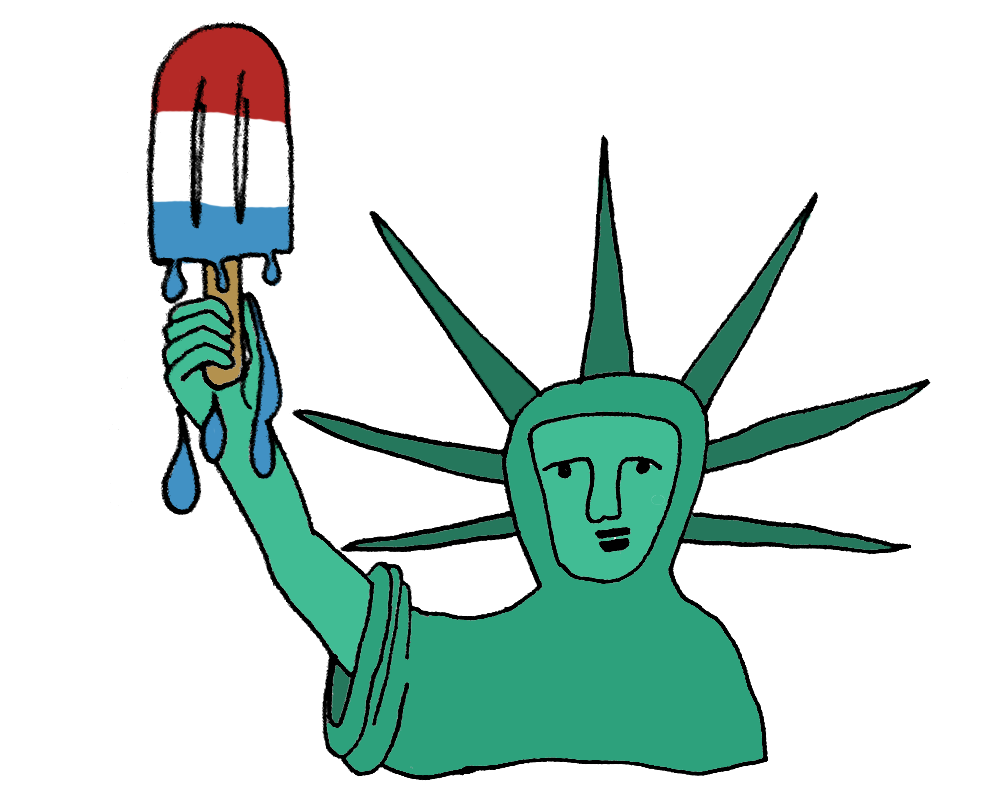

Earlier that morning, my daughter and I arrived at the front of the middle school, the middle school named Haven, no less, to find the Statue of Liberty — a teacher in a green painted gown, with a crown and torch — reading those immortal words: “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses . . . ” Classical music, swelling with emotion, played from the boom box at her feet.

The other moms and I smiled at one another. This was going to be fun. The eighth-grade social studies department was hosting a historical reenactment of Ellis Island during the Gilded Age. We’d be playing the guards tasked with guiding our children – just arrived refugees who understood no English — through the large school turned processing center. Before entering “the country,” these immigrants would have to negotiate check-in stations where they had to pass tests of medical wellness, physical rigor, cognitive acumen, and vocational potential.

The teachers explained to us that some of the children would face a fairly straightforward passage to America, while others would be detained and made to undergo further examination. Upon their arrival at the school, each student was given a card to wear around their neck. These cards, distributed randomly, specified their new name, country of origin, and age, and contained a special code that, unbeknownst to the kids, indicated whether, upon completion of their tests, they’d be sent to the auditorium for further evaluation or directly to the cafeteria.

We were assured by the teachers (probably because some crazy, overwrought mother had flipped out in the past) that all of the kids would, in fact, arrive at the cafeteria eventually, where they would be welcomed to the United States of America — with popsicles. Popsicles! Only in America — or at least in 21st century, suburban America, where everyone gets a trophy, does everyone immigrate safely and successfully and earn a popsicle!

And yet, knowing the rules of the game and the ridiculously low stakes (my daughter didn’t care whether she made it or not; she knew it didn’t matter), and knowing the horrifying realities of immigration during the late 19th century, as well as the horrifying realities of immigration today, I still worried whether my own kid would be one of the lucky ones to make it through, whether she would have a quick and happy journey, through her well-funded middle school in middle America — to the land of frozen desserts and opportunity!

I’d like to believe the statue that greeted us that morning is reflective of the grand ideals upon which, I’d like to think, this country was founded. Her script continues, “The wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless tempest-tossed to me . . . ” The poetry and sentiment are beautiful but it was never the case. No, Ellis Island was designed to separate “desirable” from “undesirable” immigrants based on the very qualities of health and wealth. The steamship companies even refused passage to thousands of hopeful immigrants every year, for fear of the stringent entry requirements as it became their financial burden to return the rejected migrants from Ellis Island back to Europe. A New York Times headline in 1891 incited, “Lunatics and Paupers Shipped from Europe” to New York. Immigrants were declared “a hopeless burden;” prejudice and discrimination abounded. Fear and loathing of immigrants is not new. It is, in fact, embedded in the foundation of our country, in the landmark, tourist attraction that is Ellis Island.

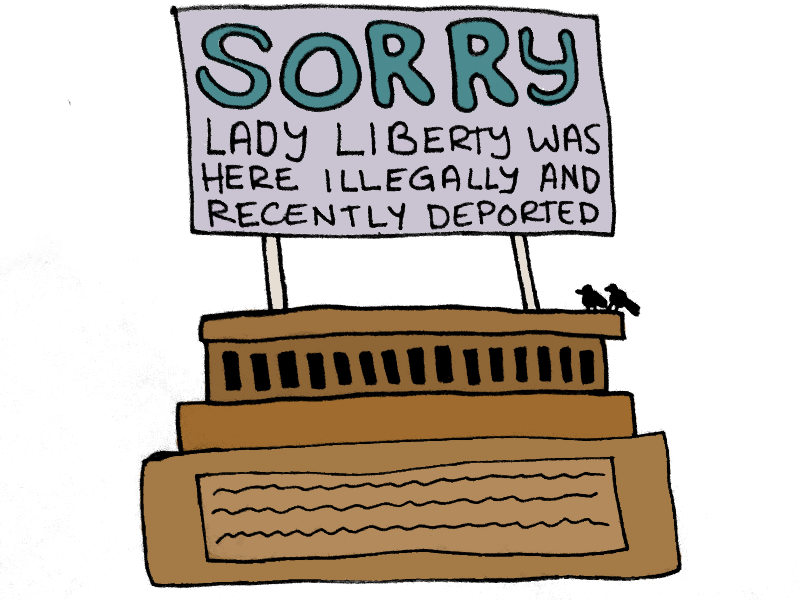

When the middle school began hosting this immersive Ellis Island experience several years ago, the concept of Ellis Island seemed more like a lesson in history than one in current events. Back when our daily dialogue was not about building walls, putting an end to Dreamers, and the separation of children from their families at detention centers at our borders. Especially given today’s climate surrounding immigration, how dare I wish for the deck to be stacked in my daughter’s favor? How dare I wish for her path to be paved? How dare I be so entitled and — American — in my perspective?

I’m disgusted by my reaction; it was visceral, irrational. I’d like to ignore it, but I can’t. And I shouldn’t. Because if I want my daughter to be happy, above all else and above all others, even in the midst of a middle school play-acting experiment, even though, as a clinical psychologist, I know the development of grit and resilience is far more important than happiness, I’m confident countless other people do too, and always have — and what does this say about our society?

If we all want the best for ourselves and our families, how much are we able to truly care about others? About the 800,000 Dreamers living in legal limbo, facing the threat of deportation, not to mention the millions of undocumented immigrants living in the margins of the United States today, as well as over 2,000 immigrant children separated from their parents at our borders this spring? What does it say about our willingness to spend billions of dollars on a wall and security to keep people out, over our willingness to provide humanitarian aid to those in need — both within and outside of our borders? Do we care only about others as long as it doesn’t inconvenience or impinge on us? Because that is not enough to protect the most vulnerable, the most in need. It wasn’t enough at the turn of the 20th century despite how much we might like to think it was better back then. And it is definitely not enough to defend, support, and provide for the Dreamers and immigrants and asylum seekers of today.

I learned a lot from being at “Ellis Island” that morning. I learned that, when push comes to shove, and this country is definitely getting pushier and shovier, I am selfish and simple-minded in my desire for my kids to be uniformly happy and successful. But more importantly, I wonder what my daughter took away from the experience. If she and her classmates made it to the cafeteria, enjoyed their popsicles, and then returned home to the safety and security of their suburban houses, what lesson did they learn? That eventually everyone makes it through? That America welcomes all — regardless of health or wealth or ethnicity? That wasn’t the case in the Gilded Age and it is certainly not the case today. •

All images by Isabella Akhtarshenas.