The punk music scene in Philadelphia is deeply rooted in the prominent hardcore clubs and bands that made the city their home in the 1980s, and it continues to thrive today. College radio stations, like Drexel University’s WKDU and the University of Pennsylvania’s WXPN, also played a crucial role in establishing the scene. While the genre frequently rages against the establishment in both content and performance, it was predominantly men who were on stage and behind the mic, giving voice to the anti-establishment message — at least in the beginning.

Or so the story of punk (particularly hardcore punk) goes. The reality is that Philadelphia’s punk scene has a much more complicated relationship with gender and with the representation of women in that scene. Looking at the broader landscape of punk today, it is not hard to see the legacy of early female punk bands, like the Slits or the more recent Riot Grrrl movement. Philadelphia is no exception to that, with many current bands that have significant female representation and have adopted overt third-wave feminist viewpoints. But this is not necessarily a new formation for Philly punk; the “institutions” of Philadelphia punk — show houses, basements, clubs, and radio stations — have been testing grounds for new and more progressive identity politics, which themselves have been reflections of broader social movements that account for feminist and queer perspectives, for decades.

Of course, this trajectory has been anything but linear, and as we have delved into its history, we have discovered that the inclusion and representation of women in Philadelphia punk are indicative of the same tensions and contradictions that run throughout gender theory and punk itself (more on that below). The inconsistent, and sometimes contradictory, nature of women in punk can be best described by music critics Simon Reynolds and Joy Press: “Instead of clearly defined trajectories . . . female rebellion is a kind of subterranean river that wells up unexpectedly from time to time, seemingly out of nowhere, then disappears below the surface again.” This is fairly representative of female rebellion in the Philly punk scene — a river that sprung forth in the early ’80s, primarily in the form of an invisible labor performed through the maintenance of that scene and that has reemerged more recently in a multitude of bands pushing forth more progressive gender dynamics.

Yeah, Philly’s Got Punk

Philadelphia often gets overlooked in many respects because it is geographically sandwiched between the larger metropolitan areas of New York City and Washington, D.C. Philly’s punk scene is no exception to this neglect. While New York had the more experimental art punk scene of the ’70s and D.C. exploded with quintessential East-Coast hardcore punk bands like Bad Brains and Minor Threat, Philadelphia was also fomenting its own little-known but formidable punk scene. The band Pure Hell (known as the world’s first all-Black punk band) helped to establish Philadelphia’s punk roots in the early 1970s, and by the latter half of the decade, punk had taken hold in Philadelphia in the form of hardcore.

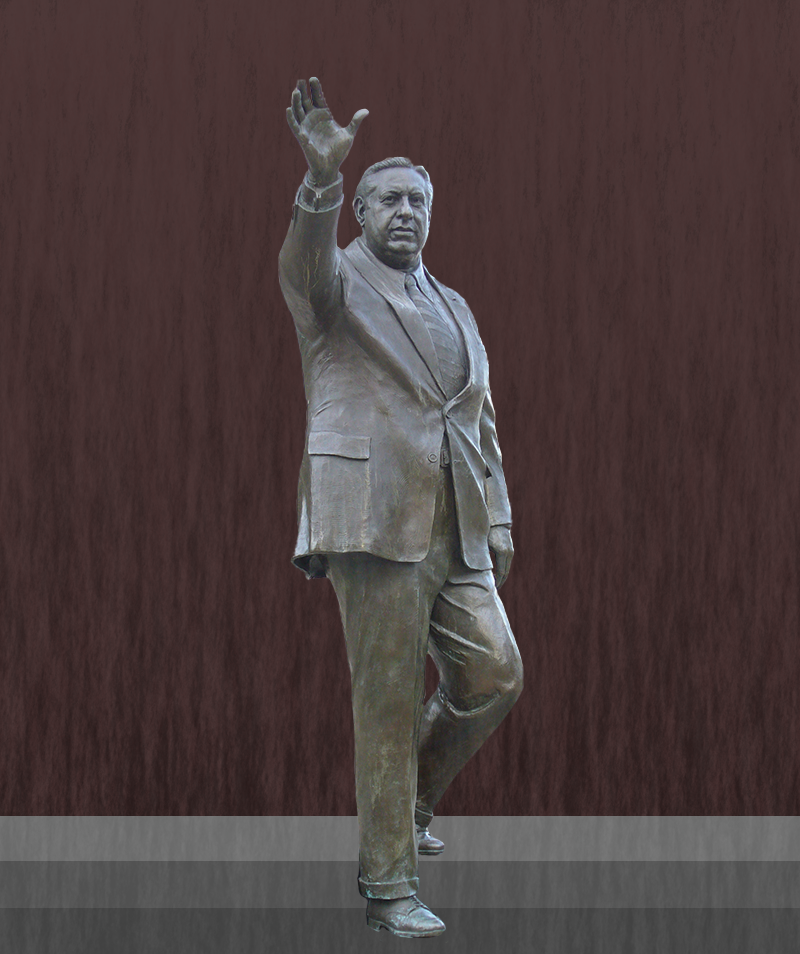

Philadelphia’s mayor at the time was Frank Rizzo, a former police commissioner. He was a political newcomer and conservative populist with a penchant for speaking off the cuff and making appeals for law and order. Rizzo wasn’t a professional politician; he was sworn in after a 1971 election which was tinged with racism and defied all voting norms.

Over the course of his eight-year term, the city was heavily divided across racial and political lines and slid into an economic slump. The city saw its population decline by 13.5 percent as it lost more than 40,000 jobs. Taxes and crime rates rose dramatically. Throughout his term, Rizzo maintained an adversarial relationship with the news media. Reverberations of the downtrodden atmosphere that permeated late-’70s Philadelphia can still be felt today in the characteristically aggressive solidarity of its citizens. But at the time, that sentiment created the perfect atmosphere for punk to trickle down from New York City and find a solid foothold.

Jake Blumgart of Philadelphia Magazine outlined the parallels between the era of Frank Rizzo and our current national political climate. It is worth noting that a reappearance of the political climate that allowed punk to first take hold in Philadelphia may cater to another counterculture resurgence in the modern day.

The year Rizzo campaigned for mayor, Drexel University’s then-AM radio station erected an antenna and became WKDU, an FM station that shared airtime with WPWT, the station of Philadelphia Wireless Technical School. Dedicated hardcore shows can be seen on the station’s schedule from as early as 1982, and punk imagery can be seen in the station’s quarterly zine, Communique, throughout the decade. Punk, in its many forms, has been in the regular rotation ever since. In a series of photographs taken by Pier Nicola D’Amico in the ’70s and ’80s of his punk friends in Philadelphia, one shows a WKDU sticker displayed on a fridge behind a dazed-looking bleach-haired punk.

Meanwhile, Drexel’s neighbor, the University of Pennsylvania, became another driving force in the punk scene. The university’s radio station frequently promoted punk bands and D.J.s on air, such as D.J. Eddie “Hacksaw” Richard. In 1978, Lee Paris’s radio show, Yesterday’s Now Music Today, was added the station’s lineup. Paris and his show are heavily credited for introducing many young punks at the time to the genre and being a fixture of the scene.

South Street was also a hub of Philadelphia punk. In 1981, Rick Millan opened Zipperhead, an iconic punk boutique that was later immortalized in Dead Milkmen’s “Punk Rock Girl”:

One Saturday I took a walk to Zipperhead

I met a girl there

And she almost knocked me dead

Zipperhead carried Philadelphia Hardcore through its peak and decline in the early and mid-’80s, respectively. As new wave took hold in the later ’80s, followed by grunge in the ’90s, it continued to operate as a center of punk and these punk-related genres. The boutique closed in 2005, but its smaller sister store, Crash Bang Boom, still distributes punk regalia just off South Street and Zipperhead’s ant-covered facade is still a South Street landmark.

During this time, there were many punk bands that populated the clubs, bars, and basement shows of South, West, and Northeast Philly; among them: Ruin, Kremlin Korps, Sadistic Exploits, More Fiends, and Informed Sources. And, as we shall see, the aforementioned subterranean river of female rock rebellion wended its way throughout this burgeoning landscape of Philly punk.

Performance Matters

The relationship among gender, identity, and music is complicated. Without diving too deeply down the rabbit hole of dense theoretical constructs, it may prove useful to think about that relationship and how the tensions within it have played out over time via the concept of performativity. Performativity comes from the work of pioneering gender theorist Judith Butler, and, as Butler defines it, it is the constellation of actions that produce the effect of a stable and natural gendered identity. In other words, gendered identities — what is perceived as masculine or feminine — come into being through a person’s ability to act within, because of, and sometimes against the pre-existing norms that shape commonly-held conceptions of gender and sexuality. Often, performances incorporate the codes of masculinity and femininity and give the impression that these acts are an essential part of a natural gendered identity. But, sometimes, and this will become especially relevant in a moment, these performances do not conform to the norm, instead eluding or transgressing it.

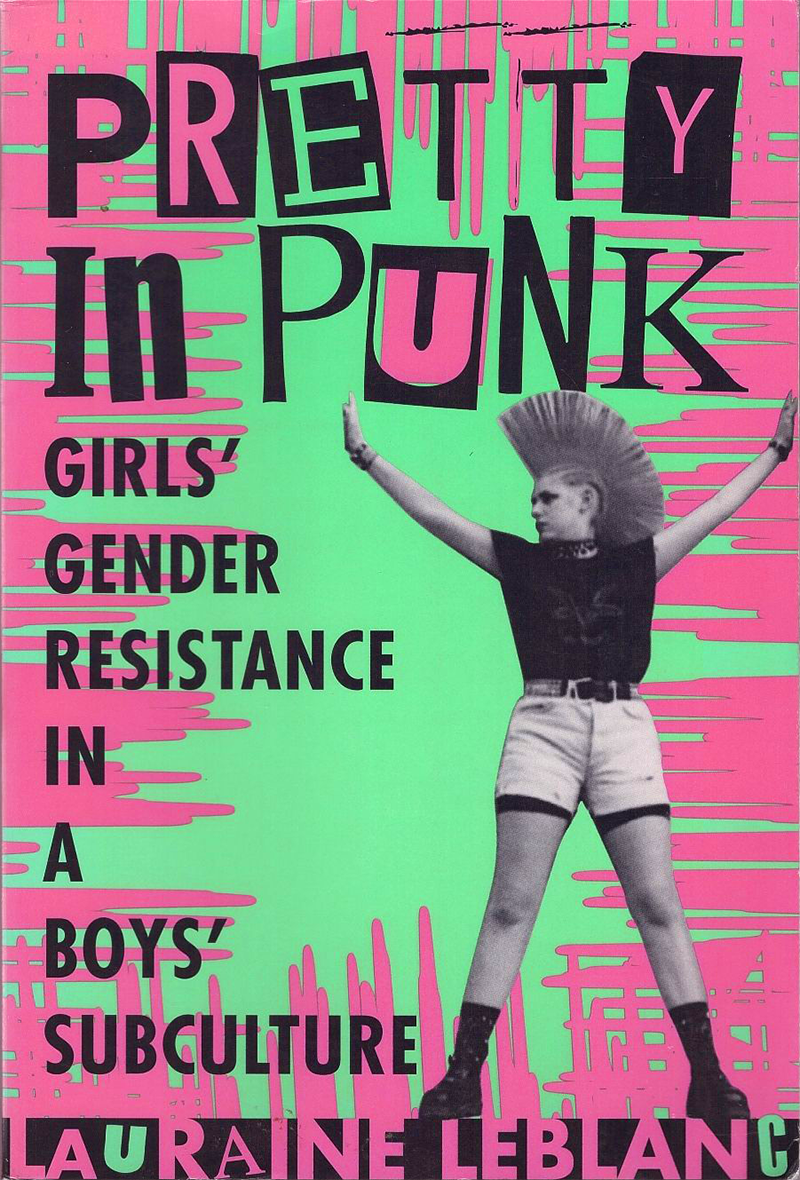

Saying that performance is central to the punk scene is beyond obvious. At a superficial level, performance refers both to the construction of gender identity and to musical performance itself. Performance on stage mirrors the performative nature of gender: There is a set of certain norms that define expectations for a live stage performance (drum solos, banter with the audience, smashed guitars, encores) very much like there are certain norms that are associated with what are considered masculine and feminine acts. Furthermore, performativity contains a central tension or paradox, in that the performance of gender creates the very means by which gender norms can be subverted (what Butler refers to as “performative subversions”). Drag is a common example of the performative nature of gender — by parodying the look and acts of gender norms through often lavish performances, drag exposes that gender is just that: performance. Such tensions play out in the punk music scene as well, particularly when it comes to gender identity. In her work Pretty in Punk, Lauraine Leblanc points to this paradox as inspiring to her research: “on the one hand, punk gave us both a place to protest all manner of constraints; on the other, the subculture put many of the same pressures on us as girls as did the mainstream culture we strove to oppose.” She goes on to note that “gender is problematic for punk girls in a way that it is not for punk guys, because punk girls must accommodate female gender within subcultural identities that are deliberately coded as male.”

Yet, punk — both in its aesthetic form and with its lyrical content — provides a means of recoding those identities. Put another way, as Press and Reynolds argue in their work The Sex Revolts, there is a constant tension that is both productive and restrictive for gender politics in punk because punk is, at one and the same time, capable of gender liberation and inherently misogynistic:

In the official history of rock, punk is regarded as a liberating time for women, a moment in which the limits of permissible representations of femininity were expanded and exploded. Women were free to uglify themselves, to escape the chanteuse role to which they were generally limited and pick up guitars and drumsticks, to shriek rather than coo in dulcet tones, to deal with hitherto taboo topics. All this is true, but . . . Punk had learned the art of defiance from ’60s mod and garage bands whose songs aggressively targeted women.

Punk, then, embodies many types of tensions, particularly in relation to gender identity: capable of liberation and subjugation; embracing femininity while valorizing masculinity; grounded in resistance and transgression while always running the risk of cooptation; subversive yet exerting its own normalizing forces.

We can think about Butler’s performative subversions in this context of punk; these subversions are a means of perpetually rendering problematic the relationship between identity and gender. As Butler argues, they are a strategy aimed at the “appropriation and redeployment of the categories of identity themselves.” The language of appropriation and redeployment is at the heart of punk, as well. For example, punk appropriated the form and energy of early rock ’n’ roll as the antithesis of the bloated pomp of mid- to late-’70s arena rock bands; at the same time, punk also appropriated the rage and struggle of racial politics and made them part of a white, working-class ethos (think of the Clash’s “White Riot”). Press and Reynolds refer to this as “racial envy,” and argue that punk has been moving towards gender tourism, defined as an imaginative space to “play” with gender. Again, performativity helps capture the ways in which strategies of gender subversion are appropriated and redeployed in punk as an imaginative space in which to play.

So, what are the strategies and tactics that are put into use in the playground of punk? Again, we turn to Press and Reynolds who, in The Sex Revolts, offer four strategies of female rock rebellion that are useful to identify how gender identity manifests in punk:

1) Straightforward “can-do” approach — i.e., whatever men can do, women can do better

2) Feminine infusion — i.e., rather than just masculine imitation, female punks demonstrate an equal but different feminine/ist approach

3) Masquerade and the subversion of gender identity (think Annie Lennox)

4) Focus not on identity but process — i.e., an approach that does not take identity as given, but exposes the trauma of identity formation

These strategies will help us frame how gender has historically operated in the Philadelphia punk scene.

Gender in the City of Brotherly Sisterly Punk

Women’s involvement in the early days of Philadelphia’s hardcore punk scene might best be described as “invisible labor.” Those involved in the scene are quick to point out that it is a misconception to think of Philly’s early punk scene as somehow devoid of, or hostile to, women. In an interview for the oral history site Loud! Fast! Philly!, Nancy Petriello Barile, who was a promoter and organizer of D.I.Y. shows in the early ’80s, argues that women were central to the scene:

Growing up in Philly, like when I hear people talk about it now, you know, oh there wasn’t, you know, women weren’t really part of hardcore or whatever, I’m like, you know, that’s bull, because, you know, we ran that shit in Philly. And, I never felt marginalized, or disrespected ever . . . I always felt really embraced by the bands and the people that were in the scene. I never really looked at it from a gender lens. I mean, I was in the front row for shows, I was in the pit for shows.

However, that level of involvement seemed to be often confined to working behind the scenes and, perhaps, being part of the crowd. Interviewer Joseph A. Gervasi notes that often the “illusion of being an outsider” comes from female participants “working on the infrastructure” of the punk scene. Petriello responds:

I think if you, you know, deconstruct a lot of the punk rock scene, you will find women behind, you know, everything. We were promoting the shows, we were managing the bands, we were writing the fan zines, we were making a lot of the stuff happen.

This role of making stuff happen behind the scenes holds true for women’s involvement in Philly punk during the ’80s — concert promotion, band management, and even running communal living spaces for nomadic punks were all part of the province for Philadelphia punk rock girls. This sort of invisible labor characterizes the performance of femininity as caretaker and nurturer. Women worked in the shadows, maintaining the infrastructure of a punk scene that allowed a predominantly masculine majority of musicians to perform publicly. In this sense, masculine performance was granted a public persona, while feminine performance operated privately to uphold that public sphere. At this stage of Philly punk, it would be challenging to map the involvement of women directly onto the typology developed by Press and Reynolds.

Another possible way to look at the early history of women in Philly punk is through the lens of tokenism. In Pretty in Punk, Lauraine LeBlanc examines the ways that punk girls were isolated from each other and became “tokens” in various North American punk scenes. Stacey Finney spoke on Loud! Fast! Philly! about how women were mostly “participants in the crowd” in the Philadelphia hardcore scene, while Nancy Petriello emphasized that women were an essential part of the infrastructure behind the scene — making zines, promoting bands, and being active audience members and pit participants — but not necessarily on stage.

That would start to change as more women became involved in bands themselves.

The presence of women in Philadelphia hardcore bands increased, including in acts such as More Fiends, Kremlin Korps, Initial Attack, and Thorazine. Finney was lead singer of the hardcore band Kremlin Corps, and on Loud! Fast! Philly! she discusses being an active participant and performer in that early scene. Gervasi asks her how it felt to be a woman involved in the hardcore scene, and Finney responds that she was one of the few at the time who was actually in a band. She says that most women:

were helping put on shows or working at clubs, but I think for the most part back then, girls, females were participants in the crowd and just in the scene at the shows. I know that in the early days with B.Y.O., Nancy [Petriello] was integral with that but I don’t think it is to the degree today and I don’t know that, I think someone like Elizabeth Fiend was very tuned in to women’s issues and things of that nature, I don’t know at that age, at least for me, that I had the maturity to think about it or care. For me, I was always one of the guys . . . so, what do I need to think about?

In essence, she affirms the “can-do” approach characterized by Reynolds and Press — women involved in and fronting bands did not necessarily equate to a gender-conscious punk scene. That sort of consciousness just was not on the radar for the early women of Philly punk (save for Elizabeth Fiend of More Fiends). Or, as Finney puts it simply: “I just did not have that awareness . . . I grew up ‘girls can do anything boys can, so fuck you.’”

At this point, we can say that women’s performances on stage strictly emulated the performance of punk masculinity. But that would not remain the case.

The punk scene in Philadelphia today has remained constant in many ways since the ’70s and ’80s, but women’s roles in the scene have changed from background infrastructure to foreground (and, often, center stage). Two major causes of this shift are women taking to the stage and the mic and women’s issues entering the consciousness of mainstream society

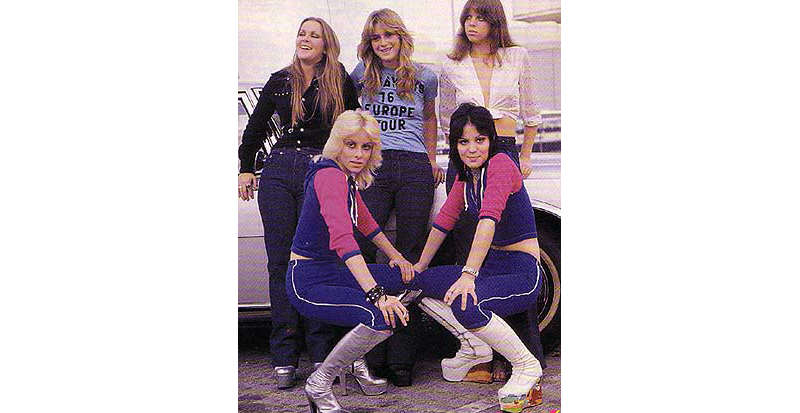

As women have more often taken the mic in the greater music landscape in the U.S. over the past couple of decades, so have women in the punk scene. The ’90s brought Riot Grrrl, the punk subgenre/submovement that took more women into the scene and banded women together to usher in a new generation of self-aware all-girl punk bands (reminiscent of the Slits and the Runaways).

As feminism crept out of the fringe and into the mainstream, women’s issues and representation became topics that were considered more natural and necessary to take into account in punk music and communities.

These and other changes bring us to the modern day Philadelphia punk scene, which more self-consciously takes on women, femininity, and women’s issues. While women have been involved throughout the history of punk in the city, these two changes gave them a more visible presence in the scene. Before, women were performing their gender within the scene in the “can-do” frame; women today are taking on their own identities and subject matter and examining the societal processes that have brought them to where they are now.

In their song “Fight Like a Girl,” the Philadelphia band Ex Friends (formed in 2011) use the strategy of feminine infusion to turn the stereotypically masculine violence found in punk towards a feminist cause, using feminine methods. This is feminine infusion, the second strategy of female rebellion identified by Reynolds and Press.

In the first stanza of the song, the band introduces gender inequality: “We don’t know when it started / We just know it’s unfair / But half the world does twice the work / And the other half’s just there.” They then urge listeners to “fight like a girl.” In the following stanzas, they outline what fighting “like a girl” looks like:

Find the ones who put you first

And do it for them too

It’s not just about principles

It’s about people, tooPick your battles carefully

Be relentless when you do

When the warnings all been laughed off

When the talking time is throughIt’s time to fight like a girl

Fight like a girl

Get down in it, don’t quit

And fight like a girl

In this song, fighting “like a girl” means finding a community, fighting for people and principles, picking battles, and never giving up on the chosen battles. The female vocalist is not arguing for the use of masculine violence against a feminist cause, but rather a completely reinterpreting what it means to fight in a feminine sense. Further, the song never explicitly makes the fight physical.

In the HIRS (pronounced like “hears”) song “TRANS WØMAN DIES ØF ØLD AGE”, the trans female vocalist addresses the trauma of identity formation: the fourth strategy of female rebellion. Though many of the trans, queer grindcore collective’s songs address the dangers and difficulties of life as a trans woman, this song confronts the reality that the process of forming and living a trans identity is so traumatic that it often leads to suicide or murder.

It might be out of spite but i will not kill myself. i will stay alive. No one’s going to kill me including myself. I’m going to live forever. The headline will read “Trans woman dies of old age.” She outlived her enemies. Homophobes rolling in their graves.

The third strategy of female rebellion, masquerade and the subversion of gender identity, could be argued to be present in the work of HIRS and other trans punk or queercore bands, but we would like to emphasize that the trans experience is recognized by the authors as the taking off of a mask, rather than the putting on. However, the trans or queer experience is a subversion of heteronormative gender identities, and in this way could be viewed as an example of this performative subversion.

Putting women on the stage and behind the microphone allows for women’s perspectives and not just their labor to be an integral part of the modern Philadelphia punk scene. When women are creators of the scene’s largest product and not just performing background maintenance, their roles extend beyond the “anything you can do, I can do better” frame and into exploring their own identities and experiences and how they arrived at them.

Outro

As we reflect on the history and evolution of women in Philadelphia punk, we can see that its presentation of gender identity remained, for a long while, in Reynolds and Press’s first two categories: the “can-do” approach characterized by the early ’80s and, more recently, feminist infusion.

However, Philadelphia punk is increasingly addressing some issues involving gender identity and the processes of identity formation, including the trauma of that formation. As we have seen, this has been largely confined to the lyrical content of songs. But, what the Philadelphia punk scene has not produced is a more radical subversion of gender identity — a performative subversion more in line with Butler’s “undoing of gender.” But, perhaps that is too tall of an order for punk as a musical form and expression of rebellion; perhaps that is the province of even more experimental and avant-garde forms of music, born out of the punk rock disruption. For example, the eclectic post-punk terrain of the 1980s was dotted with examples of more subversive female musicians — Siouxsie Sioux and Annie Lennox readily come to mind. Philadelphia has had its own post-punk experimentation as well, but that is a topic for another day.

Nevertheless, it doesn’t seem that we have quite achieved the kind of musical experimentation that might confront the issue of identity formation as process — and we aren’t just talking about in Philadelphia here, but across the punk and post-punk landscape. The issue is one of radical content meeting radical form; again, we are starting to see this in Philadelphia punk with the lyrical content of the music, but form has not matched that progression. Reynolds and Press distill the essence of this limitation:

If there’s a problem with the new surge of female activity in rock, it’s that innovations have remained mostly at the level of content (lyrics, self-presentation, ideology and rhetoric expressed in interviews), rather than formal advances . . . Women have seized rock ’n’ roll and usurped it for their own expressive purposes, but we’ve yet to see a radical feminisation of rock form itself.

The question remains: Can punk ever achieve that kind of radicalization when it is at one and the same time a form of/for disruption and of/for normalization/cooptation/appropriation? •

Feature image created by Shannon Sands. Images courtesy of nicksarebi, candyschwartz, and nikoretro via Flickr (Creative Commons). Other images created by Shannon Sands.