One hundred years ago, President Woodrow Wilson went before the United States Senate and asked Congress for a declaration of war against the Central Powers. The impetus for this declaration was Wilhelmine Germany’s return to unrestricted submarine warfare in the Atlantic. Wilson, who had a year earlier campaigned on a promise of keeping the United States out of war, now, in April, asked to send American boys to Europe in order to

fight for the things which we have always carried nearest our hearts — for democracy, for the right of those who submit to authority to have a voice in their own governments, for the rights and liberties of small nations, for a universal dominion of right by such a concert of free peoples as shall bring peace and safety to all nations and make the world itself at last free.

Wilson’s war was an ideological one, with the Allies supporting the cause of freedom and democracy (an ideal that died an ignoble death in Paris in 1919). By that June, 14,000 U.S. troops were already in France. Most “doughboys” would only know the fields of Flanders, the mountains of Vosges, and the meandering rivers named Moselle, Marne, and Meuse. Because of this, American historians of the First World War have tended to focus on the Western Front and the horrors of trench warfare.

In truth, World War I was fought on multiple fronts — in Africa, in the Balkans, in Asia Minor, and in the east towards what is today Poland, Belarus, and the three Baltic nations of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia. Each one of these fronts experienced the same horrors of the Western Front, and yet, judging by the documents left behind by both Allied and Central Powers soldiers, the other fronts in Europe contained more than a passing trace of the supernaturally strange.

In 1921, years after serving with the German Army in the Balkans, film producer Albin Grau composed an article detailing his wartime experience with the most famous creature to ever come out of Slavic folklore.

‘Do you know that we’re all more or less tormented by vampires?’ asks one of his comrades, to which an old peasant says: ‘Before this wretched war, I was over in Romania. You can laugh about this superstition, but I swear on the mother of God, that I myself knew that horrible thing of seeing an undead,’ and he goes on to explain. ‘Yes, an undead or a Nosferatu, as vampires are called over there. Only in books have you heard those strange and disturbing creatures spoken about, and you smile at these old wives’ tales; but it’s here, where we’re at in the Balkans, that one finds the cradle of those vampires. We’ve been pursued and tormented by those monsters forever.’

Grau did not rest on this tale and experience. He and director F.W. Murnau would collaborate on the revolutionary film Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens. While not cinema’s first vampire, Graf Orlok (played by German actor Max Schreck) remains the most frightening and most awful-looking bloodsucker to ever curse celluloid. On top of this, it turns out that Grau was a serious occultist and imbued the film with occult symbols that he had picked up while a member of the Fraternitas Saturni.

Two years earlier, a pair of writers, Hans Janowitz and Carl Mayer, had translated their experiences with the brutish military authorities of the Austro-Hungarian Empire into a parable about diseased autocracy, specifically that a vulnerable mind can be manipulated by a tyrant. Their product, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, was later interpreted by one German Marxist as a subconscious plea for authoritarian rule.

German and Austro-Hungarian veterans were not the only soldiers to turn their wartime experiences into terror stories. During the war, on the Italian Front, both Italian and Austrian troops were known to swap stories about ghosts, vampires, and other ghouls as artillery shells slammed into the battle-scarred Dolomites. The Italian Alpini, a special troop of mountain infantry composed of Italian-speaking soldiers from the Trentino, South Tyrol, and Friuli regions, became especially known for their superstitious nature. Tales of vampires, witches, and hobgoblins acted as the shared currency among the often demoralized soldiers serving near the Isonzo River.

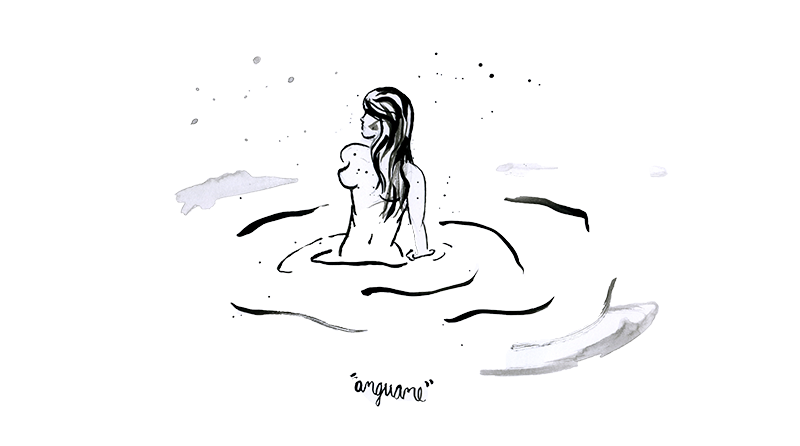

Almost every man serving in the Dolomites knew about the “anguane,” a type of witch that is known to haunt rivers and caves. The gnome-like “mazarol,” a frisky little fellow who is still widely known in Belluno today, also appears in the records of the Alpini and other Italian soldiers. Finally, the most persistently evil of all folkloric creatures, the “striga” (plural striges), supposedly haunted the battlefields in the form of blood-drinking birds of prey. In northeastern Italy today, in the same region that is still is still pockmarked by trenches and shell craters, striges and other witches are burned in effigy during the celebration of Epiphany.

Most in America are familiar with one Alpini creature — Krampus, the evil-looking Christmas specter who is celebrated in Austria, Switzerland, Bavaria, and the Tyrolean regions of northern Italy. However, few know that Krampus enjoyed some popularity as a representative of “ethnographic art” during the deadly days of World War I.

Understanding this mysticism in the face of battle means understanding the unique quality of the Alpini and the Alpine peoples more generally. Strong regional pride appeared among the Alpini during times of crisis, such as the 1916 revolt of the Cervino Battalion. According to historian Vanda Wilcox, the Alpini mutineers shouted: “Down with sergeant-major Giacchino! Down with the Neapolitan!” The cause of this mini rebellion was a haughty attitude to southern Italians. For the northern men of the Alpini, the Neapolitan sergeant-major was simply “inferior.”

Similarly, if historians like Carlo Ginzburg are correct, then the families who produced the Alpini soldiers may have been the descendants of the same peasants who kept alive pre-Christian folk tales until they suffered the hammer known as the Roman Inquisition. In his books The Night Battles, The Cheese and the Worms, and Ecstasies deciphering the Witches’ Sabbath, Ginzburg has consistently argued that the peasants of the Friuli region grafted onto official Catholicism a pastoral religion that included trace elements of ancient fertility cults.

In the early months of 1583 the Holy Office at Udine receive a denunciation against Toffolo di Buri, a ‘herdsman’ of Pieris, a village near Monfalcone — across the Isonzo river and thus outside the borders of the Friuli, although still under the spiritual jurisdiction of the diocese of Aquileia. This Tofolo ‘asserts that he is a benandante, and that for a period of about twenty-eight years he has been compelled to go on the Ember Days in the company of other benandanti to fight witches and warlocks in spirit (leaving his body behind in bed) but dressed in the same clothing he is accustomed to wear during the day.’

The “benandanti,” or “good walkers,” practiced a syncretic form of white magic that saw “good” shape-shifters descend into Hell in order to fight “bad” shape-shifters called “maladanti.” The agrarian nature of these beliefs are brought home by the fact that the good witches used fennel and sorghum (men wielded fennel, women wielded sorghum) to pummel their enemies. Notably, sorghum is a key ingredient in the witches’ brooms of folklore. Also, the benandanti believed that their members often came into the world with a caul over their heads. Many Slavic cultures believed that those born with cauls would come back to life as vampires. Friuli is after all a mere hop, skip, and a jump away from Slovenia and Austria, thus making the area a potential nexus for Slavic, Latin, and Germanic folklore.

More to Ginzburg’s point, pre-modern Friuli represented a threat to the Roman Catholic Church because the centralizing force of the Vatican could not reach the region’s independent-minded peasants. Like the miller Menocchio, Friulian peasants often translated biblical scripture into what they knew best, i.e. the changing of the seasons, the process of making cheese, or the daily struggle of making bread from the unforgiving earth. Only the Roman Inquisition, spurred on by the Protestant Reformation and the concomitant push to eradicate all forms of heresy, created a religious unity in the area. This often meant God was received on the torture rack.

But, even then folktales persisted, and the current fad of Krampus and Perchta represents a mish-mash of folk Catholicism and ancestral memories about the pagan past.

Alpini soldiers and their Austrian counterparts almost certainly knew about the old stories, and when confronted with death on a daily basis, many reverted back to superstition as a way to bring order to the mechanized chaos around them. Other soldiers practiced such coping methods as well. Refusing to light a third cigarette with the same match, loading wounded soldiers with their feet facing the ambulance, and painting skulls on airplanes all became ways for soldiers and airmen to cheat death. One can draw a rough line from these battlefield superstitions to postwar Europe’s flight from rationalism. Into the void came the Thule Society, surrealism, and the nihilistic predilections of the Freikorps and Bolsheviks. The mad Baltic German aristocrat Baron Roman Ungern-Sternberg can only be understood as an extreme example of how prewar pop occultism (for example, Theosophy) and racialism became wedded to the bestial hatred for bourgeois life that characterized so many traumatized veterans.

Italy suffered such a fate, as well. Veterans of the Royal Italian Army, especially the elite stormtroopers of the Arditi (many of which began their military careers as members of the Alpini regiments) left the war zone in 1918 in order to join the march of Fiume led by the charismatic poet-turned-aviator Gabriele D’Annunzio. There they helped to create an anarchist city-state that believed in free love, the Nietzschean “Over Man,” and syndicalist economics.

Other Arditi veterans went back home in order to become blackshirts in the new Fascist movement led by a former socialist-cum-nationalist named Benito Mussolini, himself a son of the north. These early political soldiers tended to prefer cracking skulls to contemplating politics, though. Between 1919 and 1922, the Fascist squadristi killed hundreds of its political opponents, even including socialist parliamentarians.

What, if anything, does this small story from World War I tell us? First of all, the Alpini and their solider peers dealt with the horror of World War I by reaching into the misty past. This meant sharing old folktales and participating in Catholic rituals. The Alpini were known for being both superstitious and very religious. These two qualities complimented each other as they so often do.

Also, the wartime resurrection of folk culture did not dissipate when the guns fell silent at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month. This interest in “the folk” became integral to postwar nationalist movements on the right, including both Italian Fascism and German National Socialism. In this way the myths of the Alpini continue to resonate in the modern world.

More than a spooky tale for the Halloween season, the story of the monsters of the Italian Front helps us to better understand how mysticism and metaphysics birthed two of history’s deadliest ideologies. •

All images created by Emily Anderson.