The news last month that MAD Magazine was drawing to a close (reprints will continue to be shuffled out over time, but in terms of new material the publication is kaput) was not, to be honest, that surprising. While it has had an impressive six-decade run, it, like all print publications, has had to deal with an ever-dwindling readership. Plus, it’s been many, many years since the magazine enjoyed the cultural relevancy it did in the 1960s and ’70s.

And yet it should also come as no surprise to see the number of mournful tributes that followed the news in its wake. This was more than just the sad wailing of boomers and Gen Xers about one more beloved milestone of their childhood gone to the graveyard. MAD was an institution that set the template for much of the smart-ass satire that permeates our culture today.

The story of how MAD came to be has been an oft-told tale. Let’s tell it again. Around early 1951 or ’52, cartoonist and editor Harvey Kurtzman was complaining to his boss, William Gaines, head of EC Comics, that his co-worker, editor Al Feldstein, was editing far more titles with greater success and thus making more money. Kurtzman had been overseeing a small line of war and “high adventure” comics, most notable for their eye for historical accuracy and deglamorization of war, depicting the senselessness and brutality of the battlefield and even going so far as to depict the enemy (in this case the Koreans) as human.

But these books took Kurtzman a long time to produce, mainly because he was scrupulous about details and insistent that artists follow his layouts to the letter. Feldstein, meanwhile, was prolific, gave the artists a longer leash, and edited the line of horror books, which had proved to be a gold mine for the publisher (though one that attracted a lot of unwanted attention from would-be moral crusaders). What could Kurtzman do to increase his output?

Well, Gaines said, before you came here you did those great Hey Look gag strips. Those were really funny. Why don’t you do a humor comic? You wouldn’t have to do as much research for that. You can even make fun of the stuff we publish.

And thus MAD was born, though it took a while for comic (it was a comic then, not a magazine) to find its footing. The first few issues aren’t very funny, with Kurtzman and his astoundingly talented stable of artists — most notably Jack Davis, Wally Wood, and Will Elder — weakly parodying the types of comics EC was producing at the time.

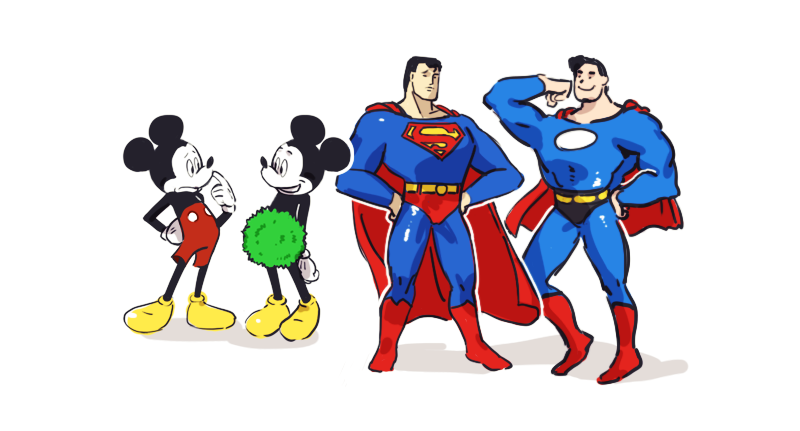

It isn’t until the fourth issue, with the sublime “Superduperman” (art by Wood) that things really started to click. Here, Wood and Kurtzman imagine Earth’s mightiest hero as a bit of an arrogant doofus who, despite his superpowers, “is still a creep.”

From there Kurtzman and his crew began to expand their range of targets, soon not just mocking popular comics like Terry and the Pirates and Little Orphan Annie, but poking fun at classic literature, movies like High Noon, TV shows like Howdy Doody, and 1950s Americana in general. By issue #17 he was even taking a swing at the McCarthy Army hearings, reimagining it as a game show, where politics has just become another form of mindless entertainment designed to sell advertising.

The formula for MAD at the time was pretty basic: fill the pages with “wait for the twist” jokes and every sort of visual gag and pun you can imagine. Don’t let any white space peek out. (Elder was particularly good at this.) But behind all the madcap frenzy all was a central thesis: Question authority. No one has any idea what they’re doing. Everyone has feet of clay. Everyone is a hypocrite. Everyone is for sale or is trying to sell you something. Even the people making the comic book you’re reading. In the pages of MAD, fantasy would run smack dab into the brick wall of reality time and time again.

With this sort of cynical outlook, it’s not surprising that the stories in early MAD could often take a dark turn. A jealous Mickey Mouse, for instance, traps Donald Duck in a zoo where he faces possible taxidermy. Sherlock Holmes murders Watson in an attempt to solve a locked-room mystery. Captain Video is seemingly killed by actual invading space aliens. Even for a kid growing up in the 1970s, this could be disconcerting stuff.

As more parents and eventually, the government started to fret about the ill effects of these creepy crimes and horror comic books, Kurtzman, wanting to do something more upscale, pressured Gaines in 1955 to turn MAD in an actual magazine, one that wouldn’t be under the thumb of the newly restrictive comic code.

But with only a few issues of the magazine under Kurtzman’s belt, Playboy impresario Hugh Hefner came courting, hinting that he wouldn’t mind expanding his empire to include a new humor magazine. Kurtzman made Gaines an offer he had to refuse — give me 51 percent of the company or else — and when Gaines said no Kurtzman joined the Playboy empire. Sadly, that magazine, Trump, only lasted two issues. Not due to any fault on Kurtzman’s part — Trump actually sold well — but simply because Hefner had overextended himself financially and the bill collectors came calling. Kurtzman tried several times to copy MAD’s success with titles like Humbug and Help, before eventually producing Little Annie Fanny for Playboy with Will Elder, a strip that became a victim of diminishing returns as the decades wore on.

In desperation, Gaines turned to Al Feldstein to edit MAD. There was little reason to think that Feldstein could do as good a job as Kurtzman on the burgeoning magazine. In the EC days, he had shepherded a MAD knock-off, Panic, that was most notable for being unfunny. But Feldstein in many ways exceeded expectations. It is with good reason that Kurtzman is seen today as one of the true geniuses of comics, but it was Feldstein that embedded MAD into America’s psyche.

There are a couple of things Feldstein did that helped turn MAD into a million-subscription seller. One, was to take the funny-looking kid that Kurtzman had been dotting throughout the magazine (he had reportedly seen the image on a postcard), give him a name — Alfred E. Neuman (which had been assigned to various nondescript characters beforehand) — and make him the magazine’s icon, their Playboy bunny or Jolly Green Giant if you will. This big-eared Irish kid with the somewhat vacant but also unflappable expression became a chameleon — Darth Vader one month, Bruce Springsteen on another — but also a symbol for the juvenile but sly humor that lay beneath the cover.

The other, more significant thing Feldstein did was to cultivate a stable of talented artists and writers — the proclaimed “usual gang of idiots” and stay out of their way so long as they didn’t go too far afield. Kurtzman had again started down that path, hiring folks like Stan Freeberg and Steve Allen to pen articles and discovering artists like Al Jaffee and Arnold Roth, but again, Kurtzman by all reports had a very top-down, strong editorial vision that suffused everything he touched. Even when someone else was producing the content, you could see Harvey’s mindset in the background.

Conversely, there was no real house style at Feldstein’s MAD beyond a general esprit de corps. The writers and artists shared little on the surface beyond wanting to poke fun at some hallowed figures and institutions. There was: Don Martin, with his floppy footed characters and peculiar sound effects that belied a dark black humor (which honestly terrified young me); Mort Ducker, the master caricaturist; Al Jaffee who offered snappy answers to stupid questions and put hidden images in the back page, only visible when folded; Cuban-born Antonio Prohías, who fled Cuba under accusations of being a spy (he wasn’t) and proceeded to pit two sharp-nosed spies, one white and one black, in a seemingly neverending game of mutually assured destruction; the sublime Sergio Aragones, who filled the margins with hilarious, teeny-tiny gags. David Berg, who exposed the hypocrisy of middle-class America with some of the hoariest punch lines around. Even some of the lesser-known stars — George Woodbridge, Peter Paul Porges, Don Edwing, Paul Coker Jr. — all had an ability to depict the grotesque with what can only be described as an adolescent cheerfulness.

Kurtzman aspired to create a humor publication that adults — or at least savvy teenagers — would enjoy, but under Feldstein’s guidance, MAD became a magazine strictly for children, albeit one that shined a light on the inner workings of the adult world. As puerile as MAD’s jokes could be, it didn’t talk down to you. The magazine satirized movies you were too young to see, TV shows your mom wouldn’t let you stay up to watch, and made references to political figures you had never heard of before. To this day I will recall seeing a movie only to realize no, I just read the MAD parody version.

Feldstein’s MAD was never quite as cutting Kurtzman’s version or its myriad successors — National Lampoon, Spy magazine, Saturday Night Live, The Daily Show, The Onion, The Simpsons, South Park, etc. — but that didn’t mean it was kind to those in power either. As Tim Kreider, writing for the New York Times, put it:

I also learned from MAD that politicians were corrupt and deceitful, that Hollywood and Madison Avenue pushed insulting junk, that religion was more invested in respectability than compassion, that school was mostly about teaching you to obey arbitrary rules and submit to dingbats and martinets — that it was, in short, all BS. Grown-ups who worried that MAD was a subversive influence, undermining the youth of America’s respect for their elders and faith in our hallowed institutions, were 100 percent correct.

Feldstein’s formula proved to be so successful that subsequent editors never strayed from the path, even as subscriptions slowly dwindled and the magazine had to eventually take on advertising in order to help defray costs.

It’s a long-running joke that MAD is never as good as it was “when I was reading it,” regardless of which decade that person is referring to. The true death knell might have been when it decided after 44 years to accept advertising. It’s difficult to poke fun at Madison Ave. when you’re cashing their checks.

But even as MAD lost relevance and readers, it picked up a considerable number of talent from indie comics circles — folks like Evan Dorkin, Pat Moriarty, and Peter Kuper. (And here’s a reminder that all things aside, the death of MAD means there’s one less place where contemporary cartoonists can actually get paid reasonably well for their work.)

And it’s not like the magazine completely lost its cutting edge. Last December’s issue saw “The Ghastlygun Tinies” by Matt Cohen and Marc Palm, a rather blistering play off of Edward Gorey’s The Gashlycrumb Tinies, where the victims of a school shooting are memorialized, primer reader style — “Q is for Quinn, whose life has just begun. R is for Reid, valued less than a gun.” It’s a rather savage slap in the face to the NRA and others who would seek to normalize the slaughter of children for their own political convenience or sense of self-worth. Looking at the strip, you can’t help but be a little sad that Mad’s owners (in this case AT&T) decided to pull the plug. There was life in the old boy yet. •