I was born in the Jackson, Mississippi Baptist Hospital on June 27, 1938, to parents Isaac Gresham Riley and Vernella Gertrude Riley; a younger brother (Keith) would come along three years later. Both my parents were in their early 30s at the time and had only recently moved to Jackson from farming communities located in the most impoverished parts of rural Mississippi. Jackson (the capital of the State and population at the time — 48,282) would be my home until I graduated from high school in 1956.

My father had a high school education; my mother was a graduate of a small teachers college in the State but never taught in a school system. Basically, they were “urban transplants” from hardscrabble farms. My father was a shift foreman in a chemical manufacturing plant located in Jackson, a blue-collar job that never paid as much as $10,000 a year. My mother was a wife and a full-time homemaker.

In reflecting on the first 18 years of my life, I can easily identify eight features that shaped my childhood in the rural South:

- A stable family life

- The nuclear family and immediate kinship groups as the dominant community of which I was a member

- Southern Baptist Protestantism as embodied in our local church, Griffith Memorial Baptist Church

- Pervasive racism

- A class-stratified, feudal society within the White community in addition to racism. (Think of “hicks” or “rednecks” in Robert Penn Warren’s “All the King’s Men“) There was no sense of an encompassing community.

- An emphasis on education in my family (as well as other low- to middle-class families), but within an environment of general contentment with/acceptance of ignorance, poverty, and poor health.

- Existence of a distinctive Mississippi culture combining an uncomfortable relationship between racism on the one hand and a strong pride in a Mississippi literary tradition that challenged that very racism on the other.

- Self-reliance as a virtue, but for no reason other than the absence of an encompassing community that might serve as an alternative.

I developed this list after having lunch with a friend to discuss a book that interested us both, Steven Conn’s The Lies of the Land: Seeing Rural America For What It Is — And Isn’t. The main questions Conn raises and addresses are: What is rural America? Does it exist or has it ever existed? If so, are its main features those prominent in the popular imagination: populated by self-reliant Jeffersonian yeoman farmers; the effortlessness of forming personal relations; and the distinctiveness of generosity of spirit and absence of malice? Is rural America where, in the words of 2008 Republican vice-presidential nominee Sarah Palin, one finds “real Americans”?

In general, my friend and I thought Conn’s analysis to be timely, important, and (for the most part) defensible. Where we differed was the extent to which his analysis “mapped” our experiences growing up in “rural America”; He is from upstate New York; I am from the deep, deep South. For him, the “myths” Steven Conn debunks of rural America, he found alive and well in his community. For me, I believe that Conn’s analysis is spot-on, with one major exception. And, in exploring more deeply this one exception, I argue that there is evidence in support of the conclusion that the common view of rural America is worse than mythical; it’s a tissue of lies.

A strength of Conn’s study, I believe, is his use of the distinction between “place” and “space” in defining “rural America,” a designation itself poorly defined, if ever defined at all. The term “place,” for Conn, “tends to connote specificity, authenticity, and stability.” “Space” on the other hand, “is an abstraction: empty space, outer space. Places imply belonging and rootedness. Space implies none of those things.”

On the basis of this distinction, Conn defines “rural America” as spaces not places; more precisely, sparsely populated and therefore high-maintenance spaces, which “don’t embody sets of values or ideologies, but rather conceal them.” Consequently, he concludes that there is not “much real evidence that the United States developed genuinely distinctive rural societies or cultures.” Quoting David Foster Wallace, the novelist from downstate Illinois, Conn drives the point home with the following: “Rural Midwesterners live surrounded by unpopulated land, marooned in a space whose emptiness is both physical and spiritual.”

As a generalization about rural America, the absence of “a set of values or ideologies” may be accurate, but not about the Mississippi of my youth. It was a well-defined rural society with a distinctive culture, one that was not concealed but there for all to see who had eyes to see. Foremost among those features was pervasive racism, a reality that was perplexingly obvious to a child of six or seven. Due to a variety of circumstances, among my closest playmates prior to entering the first grade were Black children of my age. That ceased to be the case once I entered elementary school, with no explanation given by my parents other than vague references about a new phase in my life. The void left by the absence of my earliest companions was not made less painful by going to school, and it continued to be a lingering presence.

Because I learned to read at an early age and because Jackson was a safe, small city for children to navigate comfortably, I was given a highly prized card to the city library and permission to take public transportation to and from the library. Even a child in elementary school could not be unaware of the enforced back-of-the-bus seating for Blacks. And then at the library and all other public buildings, there were “Colored Only” signs attached to water fountains and bathrooms. African Americans were not permitted to enter my home through the front door; I received first-hand a chilling introduction to the uneven administration of the literacy requirement to vote when I registered the first time; and segregated but vastly unequal schools were the reality until after my high school graduation. Brown v Board of Education was not handed down until May 1954.

Not only was racism pervasive, but it was also defended (indeed justified) by a second feature that defined the culture of my youth: Southern Baptist Protestantism as embodied in my family’s neighborhood church, Griffith Memorial Baptist Church, and its minister, the Reverend Louis Ferrill. Regular church attendance (twice on Sundays and every Wednesday evening for prayer meetings) was the routine 12 months of the year as was daily Bible study. By the time I graduated from high school, I’m sure I had read the entire Bible at least twice and memorized many passages. Familiarity with the Bible was reinforced by games such as “Sword Drills” in which youth such as myself were lined up in front of a drillmaster who would call out a biblical passage (say, I Corinthians, 13:13), and the race was on as to who could find the verse first. The winner was then required to read and explicate the passage.

Notably absent from Sunday and Wednesday evening sermons were homilies on what I learned later to be the “Social Gospel,” the ethical teachings of Jesus which laid out his followers’ obligations to their fellow human beings. Gradually, it dawned on me (about the ninth grade) that this omission was deliberate because of the implications of the Social Gospel for the treatment, not only of other Whites, but of African Americans as well.

In contrast, segregation and racism were actively defended/justified on what seemed dubious grounds to me, even at an early age. Namely, an alleged curse on Ham’s son (Canaan) by Noah, who in a state of drunkenness had been the object of a shameful act by his son, Ham: an act never explained other than “having seen the nakedness of his father.” The curse carried with it the Black skin of Ham’s descendants and the enslavement of Black people thereafter.

Early in my college career, it became increasingly clear that I was an atheist and that the roots were ironically to be found in my Southern religious upbringing: the disconnect between my understanding of the New Testament and the treatment of African Americans by my fellow Mississippians; the implications I had drawn from long/close Bible study about meaningless suffering, especially those found in the Book of Job; and the aggressive use of Judaic-Christian scripture to justify enslavement, segregation, and racism.

Now, at the age of 85, I live comfortably with my atheism in full awareness of and gratitude for its roots having been nourished in the soil of the religious culture of the rural South. For this reason, it is not an oxymoron to self-identify as a “Christian atheist.”

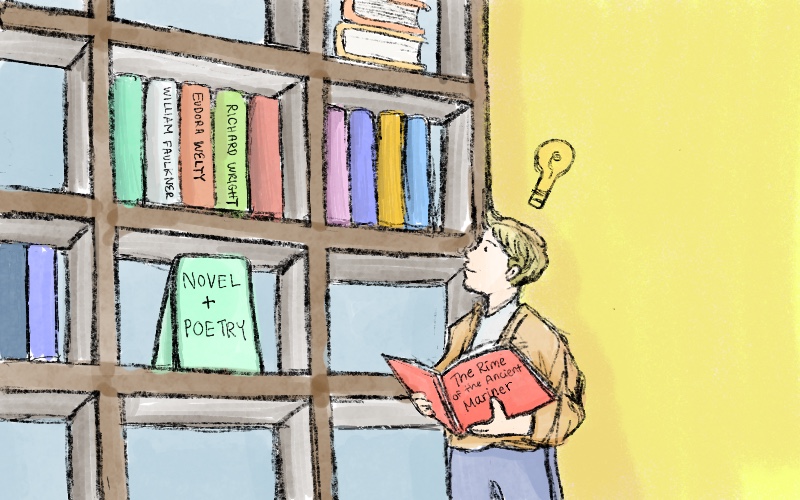

A third feature of the distinctive Southern culture that shaped my youth was the ironic and uncomfortable relationship that existed between pervasive racism on the one hand and a strong pride in a Mississippi literary tradition, which challenged that very racism on the other. I’ve already mentioned having learned to read at an early age. That skill provided the foundation for my coming alive intellectually and escaping the provincialism of my native home. The process began in a serious way (as I recall) in the ninth grade when we were assigned “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” as a reading and discussion exercise in a literature class. At the same time, I, and a small cohort of classmates (for reasons I’ve totally forgotten) began reading the editorial pages of The Clarion Ledger and The Jackson Daily News, the City’s two daily newspapers.

Of greater significance, however, was the encouragement of my school librarians and the librarians of the Jackson Public Library to read the publications of three Mississippi authors who had achieved worldwide acclaim: William Faulkner, Eudora Welty, and Richard Wright. The inclusion of Faulkner and Welty on this list is not surprising, that of Richard Wright more so. By the early 1950s, Wright was long gone from Mississippi, having gained an international reputation as an author of novels, short stories, poems, and non-fiction. In addition, he was a high-profile member of the Communist Party in the 1930s who achieved even greater fame for being driven out of the Party because he was an “intellectual” who could see more than one side to social and political problems.

Richard Wright was of interest to my librarian mentors, however, because much of his literature dealt with racial themes, “especially related to the plight of African Americans’ enduring discrimination and suffering during the late 19th to mid-20th centuries.” Consequently, by the time I graduated high school, I had read a goodly portion of what those three Mississippians had written.

There are two memories from that experience that I carry with me to this day, memories that have shaped the person I am in multiple ways.

First, there is the protagonist, Bigger Thomas, in Wright’s novel, Native Son, who lives in utter poverty on Chicago’s South Side in the 1930s. While not apologizing for Bigger’s crimes (including murder), Wright portrays a systemic causation behind them. A society that systematically denies dignity and freedoms to a segment of its population creates an environment in which they will seek both through acts of destruction — and ultimately the act of self-destruction.

Second, the renowned short story writer, Eudora Welty, lived on North State Street in Jackson, only blocks away from Central High School which I attended. My literature teacher in, I believe, the 10th grade, invited Ms. Welty to talk about her stories and literature in general with my class. This proved to be an epiphanal moment. If you have seen photographs of Eudora Welty, you will know that she was an unattractive woman. In fact, the immediate thought that went through my adolescent brain when she entered the classroom was: “My, this is the ugliest person I’ve ever seen!” And then, and then — she began to talk — talk about her stories and the art of writing. My second thought was: “This is the most beautiful human being possible.” Before the modern movement began, I became a feminist in the 10th grade.

A fourth and final feature of the distinctive Southern culture of my youth was the importance of and emphasis on education in my family. This was also true of other low- to middle-class families as evidenced by the cadre of peers who shared my interest in reading/discussing daily editorials in Jackson’s newspaper. What caught my attention at an early age, however, was the contrast between this value in a subset of my culture and a larger environment of general contentment with an acceptance of ignorance, poverty, and poor health.

In arguing as I have (contra Steven Conn) that the rural Mississippi of my youth did, in fact, possess a distinctive, visible culture defined by the four features discussed so far, I have indirectly supported his debunking the idealized myth of rural America. The myth of self-reliant Jeffersonian yeoman farmers, who lived in communities defined by the effortlessness of forming personal relations, generosity of spirit, and the absence of personal malice.

I close with two observations that reinforce the puncturing of that myth. My experience was that the nuclear family and immediate kinship groups constituted my “community,” neutralizing possible efforts to think about and implement “a common good.” In addition to pervasive racism, a class-stratified, feudal system existed in White culture. One only has to think of Huey Long’s courting of “the hicks” and “the rednecks” in his quest for political power to appreciate the absence of an encompassing sense of community even among Whites.

In this absence, “self-reliance” (to the extent it existed) can be seen as the parasitic, rather than autonomous, value it was. There was no alternative in an environment where there was no incentive to seek a common good. We come back at this point to the power of Southern Baptist Protestantism (indeed of Martin Luther) in shaping Mississippi rural culture. The doctrine of the priesthood of the believer! If the destiny of the soul for eternity depends on what the isolated believer does or does not do, there is a powerful incentive to embrace self-reliance.•