TSS: What got you interested in journalism and reporting? What were your motives going into this field?

WL: I think what got me interested was that I was good at it. I started working for my middle school newspaper in eighth grade and my high school newspaper for four years and [journalism] just became a thing that I did. I wasn’t good at math class or science class and I didn’t like homework, so like even history and English, which were my strengths, I didn’t do the best at.

I was really good at the newspaper. I really loved it; I really enjoyed it. So, first day of college or even before college: show up at the college newspaper and get started there. Did that for four years. That all kind of begets what comes afterwards.

Now, I have to note that my dad is a journalist. I do think there’s something to be said about growing up in a home where journalism was seen as something that was noble. Where it was seen as a desirable field to be in. Where the first person who woke up in the morning needed to go outside and bring the newspaper in. Where after dinner, we sat down to watch the news at night. I think that that’s something that a lot of my contemporaries, my peers, didn’t necessarily have. That’s something of a bygone generation. Our family was still structured that way.

TSS: What kind of stories were you doing before Ferguson?

WL: Now, when I was in Boston, I was doing politics, but I also had a GA [general assignment] component to that, so my day would very often start at the crime scene and then maybe end at City Hall or end at a meeting. I had some experience. I had done some officer-involved shootings. Also, in L.A. I did a few officer-involved shootings

But I always had an interest and a desire to, no matter what it might be, try to tell stories that I thought might otherwise be underrepresented in a media that’s still primarily white. Especially our newspapers. I covered the mayor’s race in Boston. Part of that meant focusing on the new diversity of this field but also looking at issues like public safety that perhaps were major issues in the black communities, but weren’t necessarily being talked about across the city. When that came to covering Congress, it was maybe focusing more on the efforts to renew the Voting Rights Act or efforts to renew long-term unemployment insurance, as opposed to just whatever the political football of the day is: Bowe Bergdahl, immigration reform . . .

TSS: How quickly after your arrival in Ferguson did you become part of the story? And was it the first time you’ve become a story?

WL: We were arrested on August 13. I had gotten there the 11th, so it was my third day there. It was completely uncomfortable and disconcerting. In those moments, you have an inclination to defend yourself and to keep talking, and you also – there’s this frustration, because you have this desire to explain yourself, and once you become an element of the story, many of the people interacting with the story are not good faith actors anyway. You are a data point for them to use to drive home whatever preconceived notion they already had.

TSS: The video’s online. We can all see.

WL: Yeah, no. It just didn’t make sense. We had reporters taking bad leaks from cops and claiming inaccurate things, like “A bunch of other people had already left the restaurant and these guys went staging a sit in.” There’s all these things that just objectively weren’t true.

Every journalist should have [a story] that they’re very close to be covered once, so they can see that people aren’t completely making it up when they say we get a lot of things wrong. Because you’re reading article after article after article about something you literally just lived through, watching your own quotes be taken out of context. And you’re like: This is really frustrating. This is terrible. None of these people know what they’re talking about.

It was not particularly comfortable, but that said, [Ryan J. Reilly of the Huffington Post and I] kind of rolled with it a little bit, because it provided and platform and it provided attention [to the issues]. It’s unfortunate to look at. But when you look at the media mentions, when you look at the social media attention to Ferguson, the 13th is the day that it goes through the roof. You got this arrest during the day of myself and Ryan. You had also a daytime protest that the police responded in force to. So you had photos of officers looking through sniper scopes at church ladies singing hymns. You had these very compelling visual images. Then [our arrest]. Also that night, Antonio French, who’s a St. Louis Alderman, gets arrested, and he’d been a very prominent figure in this. He gets arrested. Tymaine Lee at MSNBC is getting tear-gassed live on TV. This was a remarkably compelling day for this story in total.

TSS: Did you ever think of going off the story because you had become part of it?

WL: I never did. I would have never been comfortable with that, and I don’t know what message it would have sent. I do think it’s important and I appreciated the Post always kind of had my back, both publicly and privately, about what was going on as I was being attacked. I thought that was really important. But I think it was important to see that story through. I don’t know if it would have fulfilled my journalistic duty to then kind of exit that story.

One of the things I pride myself on was that even after that, we had months of coverage of Ferguson, and now years of coverage of policing. I went [to Ferguson] to elevate the coverage, and then for the years since then, we’ve been able to continue to drive this conversation about race and policing in the United States of America. I think that we were given a unique platform and a unique attention to do that. I’m glad that we were able to achieve that.

TSS: At what point did you realize that there was a movement coming out of Ferguson?

WL: Immediately. Almost every other reporter I’ve talked to who spent time there, no matter at what juncture they showed up, said the physical feeling and manifestation — I think in the book I had talked to Brittany Noble, friend of mine who is a reporter in Saint Louis, and she was one of the first reporters at the scene. She gets the interview with Michael Brown’s family. She covered police shootings in her previous job. She covered a relatively controversial shooting in Michigan, and everyone would always say, “Yeah, we’re going to protest for justice,” or, “We’re going to stay here . . .” Then, by tomorrow, it’s all dissipated.

That was not at all — she knew immediately. This is something big. The pain here, the anger here is different. I got there, and after I went to Michael Brown’s family’s press conference, I left and went to this community meeting at a local church, hosted by the NAACP. I get there, I’m pulling up, and there’s a hundred, two hundred people in the parking lot. I’m thinking, “Well, must not have opened the doors yet. Maybe there’s some media entrance or something.”

The meeting is ongoing. This is the overflow. There are two hundred additional people who can’t be seated in this large church who’ve decided that they’re going to wait in the parking lot to hear what was said in the meeting after people come back out. Who aren’t even in the room and who are waiting in the August sun to be told by someone coming out what happened.

TSS: Were you surprised how it was being interpreted outside your reporting?

WL: I was not surprised just because there was a bit of a playbook to this, and you kind of know what’s going to happen. It’s interesting watching it happen and watching it happen to people you know and texting them about it and talking to them about it. I get this all the time: “Why won’t you ask the — insert person — about the violent riots?” Because I’ll text them right now and ask them, and they’re going to say, “Yeah, of course I don’t want [violent riots].” It’s insulting to even ask the question because I have an accurate understanding of who they are and what they believe and what they want.

TSS: You would be demanding people denounce shootings of police who never advocated shooting police.

WL: Correct. It sets up this straw man. One of the reasons that I can build new relationships is because I don’t ask dumb questions. I think that becomes hard, becomes a push and a pull and a give and a take.

And I think that the media’s very powerful in our portrayals and in the limitations of our portrayals. If you have however many cable networks playing a video of a single inflammatory chant a hundred times, thousand times, two thousand times, that’s going to become one of the primary images or sounds that people who are otherwise not engaged in this are going to associate [with the story]. Then, when every time you have someone on, you reference and bring it back up, it continues to codify a significant [event]. What 15 people chanted in Minneapolis one time is not actually significant to all of these other things. What a hundred people chanted one time in New York – also is not significant to all this, but I think that becomes difficult.

There is this moment in Baltimore, Deray McKesson on with Wolf Blitzer on CNN. He was a Minneapolis teacher who drove into Saint Louis to join the demonstrations, and he became a school administrator and became very prominent. He’s from Baltimore. When Freddie Gray was killed, he’s back in Baltimore and involved in the demonstrations and involved in a lot of the organization. He’s doing this interview with Wolf Blitzer, and Wolf Blitzer just wants to get him to say that he condemns the violence, that he condemns the riots. Back and forth. So Wolf Blitzer says, “However many buildings burned down, you condemn that, right?” He goes, “Baltimore police have killed six people this year. You condemn that violence, right?” This back and forth. He was going to say that broken windows aren’t broken bones. I mean, the reality is that when the police kill someone, the government is killing someone.

TSS: Well, what we’re heading to is what you talk a lot about in your book, which is the false equivalents: The idea that we need two sides.

WL: No. Because quite frankly there isn’t two sides. If there are two sides — even if we accept that paradigm for the sake of the argument — which side deserves the scrutiny? The dead person or the agent of the state who killed them? Even if it’s a “good shooting.” Or even if it’s one that was unavoidable. We need to independently come to that conclusion for ourselves, and then we need to have a conversation about it. Even if it seems unavoidable, is there perhaps a policy that could have been different? We want to force everything into this black and white, cops and robbers, good guys and bad ideas dichotomy. We teach our kids that. Reality is, we live in a world that’s full of gray. That’s not actually how it works. Not every bad guy deserves to be dead in the street.

Even today, they charged this police officer in Milwaukee for the shooting of Sylville Smith — this guy was killed earlier this summer. Caused some riots and protests. The story was Sylville Smith had gotten out of his car and ran from a traffic stop with a gun in his hand and turned around and pointed the gun at the cops. And they shot and killed them.

That was the story. For months. Today, the DA says, “Well, he got out of the car.” It’s on body camera. Got out of the car. He runs away. He goes to throw the gun over the fence, the cop gets scared while he’s throwing the gun, shoots him once in the arm. Sylville Smith, who’s now thrown his gun, has been shot once, falls to the ground. And the cop runs up on him and shoots him in the chest and kills him.

We now have gotten to the point where, for so long it was like, “Well, he’s a bad guy with a gun and he pointed at the cop. He was raising the gun.” We just now be getting to the point where some of us can contain within us the depths and the nuance to begin to have a conversation about perhaps in a nation of tens of millions of guns, there are people begin killed in the vicinity of a gun who should not have been shot and killed. Perhaps. That is a conversation we couldn’t even begin to have two years ago.

TSS: Now, on the flip side, you have to also keep up your sources with the police. How do they react to your reporting?

WL: Well, I think there’s a major divide in policing between the leadership and the rank and file. Because your union leaders are representing your rank and file. It’s actually remarkable because they also function differently than most other unions. I say this all the time, “I’m a member of a union.” If I get caught plagiarizing some stuff tomorrow, the union’s not going to be holding press conferences saying, “This is a witch hunt against the media. He did nothing wrong. Innocent ‘til proven guilty.”

TSS: You’re Stephen Glass, Jayson Blair, you’re gone.

WL: Rightfully so. It’s a means of maintaining a certain level of professional standards in a profession. You’d be hard-pressed to find a police union that has ever once thought any police shooting shouldn’t have happened.

RA: Really?

WL: It’d be very hard to ever find any public statement — I challenge anyone to find any public statement from a police union that’s like, “Yeah, that cop shouldn’t have killed that guy.” I don’t know of one.

Now, we build relationships. I think many of the police, the chiefs, some of the officers, many of the unions, like the data work we do. It validates them, largely, that so many of the people we kill are armed and dangerous and attacking. Which is something we found. It’s not that police are never killing bad guys who are attacking them. They are. Very often. But I think my job is to provide a level of accountability and transparency to the government. To powerful people. Police are the people in power.

On top of that, when I parachute into Charlotte or Cleveland, doesn’t really matter if a police chief ever talks to me. I don’t need access to him. It’d be nice to have that. We call and we ask for it, but I’m not the local cop reporter. I’m here to cover this thing, which means maybe I can ask a question or frame something in a more accurate way that it hits them a little harder, because they’re most likely not returning my calls already. That’s a big part of the calculus for me. When they think they can play this game with you and woo you, and when they think you’re pliable like that, they take advantage of it. When they know you’re going to hit them no matter what, now they have some incentive to return your phone call. Because we might as well get our statement in this thing.

TSS: Talk about the title of your book. It’s in quotes, which is pretty unusual for a title.

WL: “You Can’t Kill Us All” comes from a sign at the shooting of Antonio Martin. Antonio Martin’s killed in St. Louis not long after the non-indictment of Darren Wilson in Ferguson. I want to say he’s the first person killed by the police in greater St. Louis after [Michael Brown]. Someone left at this protest this cardboard sign that said: “They Can’t Kill Us All.”

I get a lot of calls and emails from readers who read that story. “Why are people in the streets? What’s everyone so upset about? I don’t really get it. Like didn’t that one guy deserve it? What are these protests all about?” I tell people, I tell them that I think that we make a mistake when we try to focus on the 100,000 people. I think that you start by trying to understand why one person’s here.

If I can tell you the story of Johetta Elzie or DeRay Mckesson or Bree Newsome, you can understand them as a human. Why this person — based on their limited experiences, based on their motivations, their goals, their lives — why this person stepped in the streets. If I explain that to you, then you might understand why nine other people are there, too. And then you’re going to understand one and you’re going to understand ten and then you can understand the 10,000. I see this book as telling the stories of ten, 12, 15 people as a means of telling the stories of the ten, 12, 15,000, or millions of people who have taken to the streets. I wanted the book to encapsulate what is the shared ideology or the shared message that all these people in the streets were attempting to express. Because you can’t kill all of us. We’re going to keep standing here until something changes.

TSS: What do you think happens next with this story?

WL: Well, I mean, we know the police haven’t stopped killing people. I think that there certainly seems to be a lot of recalculating right now. I think the presidential election went very differently than most people expected it to, much less people in these spaces. And so what was I think a plan of years of agitation to force a movement further left of the Department of Justice now likely becomes a much different kind of strategic task.

But policing is also something that is reformed and changes at local levels. I think we have seen, whether it be through efforts to get rid of law-and-order DAs and bring in reformer types, whether it’s legislation we’ve seen in some states to force independent review of police shootings, whether it’s now the precedent [in] the policing best practice across the country that errs towards transparency in terms of some of these shootings. We’re seeing some of the manifestation of that.

TSS: If you could think of a couple of reforms or a couple departments that have really stepped up to the plate, what would you suggest? Who would you point to?

WL: I think it’s hard to look at any individual department because every department has its things, but I think that there’s a few. You look at what NYPD has done with their critical response team with dealing with people who are mental and emotional health crises. And they still had some incidents involving people with mental and emotional health crises that have not been handled correctly, but they have one of the gold-standard teams in terms of the amount of training.

I think very often of individual chiefs: Art Acevedo, he used to run Austin and has just now moved to Houston, and Ed Flynn who’s in Milwaukee. One of the things I think is very important is the willingness to speak out and speak freely and to discipline officers when they do something wrong. I think that the reality is most police shootings are going to be legally justified. By most, I mean all of them — statistically. If you had 990 shooting in 2015, 18 result in charges, that’s less than one percent. Literally, statistically, about one percent. Statistically, no police shootings are illegal. You round your one percent down to zero. But what we know is that hundreds of the shootings could have been prevented or were a violation of department policy in some way.

TSS: Are you saying that police are a little too focused on whether this shooting is technically legal versus did we need to kill someone?

WL: Yes. In our society, we definitely are. Every police shooting, almost every police shooting, is legally justified because if the police officer said they were scared, they are allowed to kill people. Because of that, I think it’s really important to have departments [that] are willing to hold officers accountable.

I mentioned Art Acevedo in Austin. They had a shooting earlier this year, 17- or 18-year-old David Joseph. A young black kid who was under the influence of some psychotic drug or in the midst of some massive mental health breakdown. But whatever it is brought David Joseph here, he’s in the middle of the road, standing naked, running around. An officer pulls up, Geoffrey Freeman. Pulls up. Gets out of his car, and the naked boy starts running at him. And Officer Freeman pulls his gun and shoots and kills this kid.

TSS: He was naked. He had no gun. He was unarmed.

WL: Acevedo says anyone who has a naked teenager at them and feels so threatened by that they need to shoot and kill that person is not somebody who needs to be a police officer in my department. This is the second naked black to be shot and killed in two years in the United States of America, and before that Anthony Hill case in Georgia.

He fires this officer. The union flips out and the rank and file are mad at him and they’re audio recording every talk he’s giving to people and leaking it to the local press. But the officer wasn’t charged for that shooting. He said he was scared for his life. Unreasonable person was charging at him and he was scared and so he shot and killed him. This is legal, but was it a violation of policy? Was it a shooting that was preventable? Was it. . . ? So we have to have a level of accountability at the departmental level. •

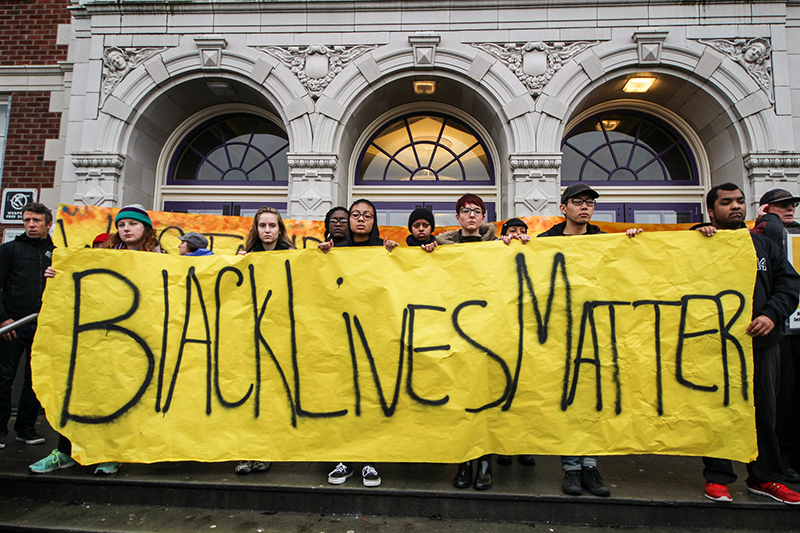

Images courtesy of Overpass Light Brigade, Aramil Liadon, Overpass Light Brigade, scottlum, velo_city, scottlum, Annette Bernhardt, and ep_jhu via Flickr (Creative Commons).