Content note: discussion of childhood sexual assault

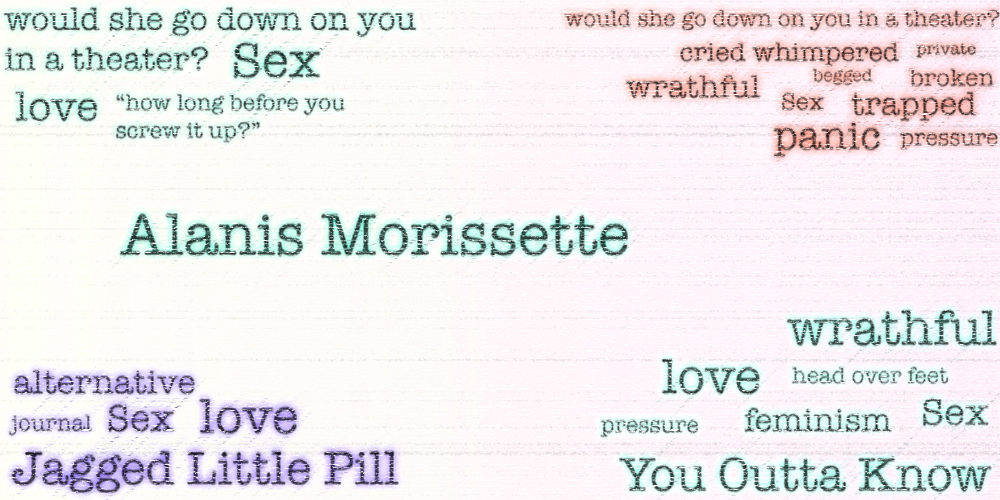

“I would love to go down on you,” is what my mom’s boyfriend said to me when he held me down on a bed when I was 13 years old. The only other time I had heard the phrase “go down on” was in Alanis Morissette’s “You Oughta Know,” in which she famously reveals her predilection for performing the act theaters. Jagged Little Pill, the album from which the song came, was released in June 1995; I bought it that summer, ten years old, and voracious for these songs that felt like a portal. It’s about sex, my friends whispered in agreement about that line, although we weren’t sure exactly what kind of sex. Three years later, trapped below a 200-pound man who smelled like Listerine and gasoline, I still wasn’t sure exactly it meant, but I knew I didn’t want it from him.

All of this started in a doorway of his daughter’s bedroom where I began sleeping after mom declared bankruptcy on our home and his ex-wife took their kid. I was on the bed opening my journal, which was a standard, nearly daily practice. But this time, when I opened the book, loose pages fell out. I panicked — I had not put anything in the journal. I unfolded what I saw was a Xerox copy of my last few journal entries, the ones where I’d been writing about making myself throw up my food. About wanting to be thinner. About hating my body. About my routine of drawing a bath and pressing play on the Discman from which I’d blast a Sarah McLachlan cd so loud that you could hear it through headphones so that the combination of the music and the water would drown out the sound of me retching. And how I’d lock the door even though my mom made me promise I’d never do that in the shower or the bath because if I slipped, she needed to be able to open the door. And how I had kept that promise for my whole life until now, but I just couldn’t risk her catching me throw up, and also, I wrote, because of Ron.

My heart rate was out of control. In that instant, Ron appeared in the doorway.

“I did this to help you,” he said, or something along those lines. “You shouldn’t do this to yourself,” he slurred, “You’re beautiful.”

I protested. How could you do this? This is my private journal.

He moved from the door toward me, closer and closer.

I think I was sitting. I must’ve been. In swishy pants (that’s what I called them, these ugly old track pants) and a powder-blue sweatshirt, braces, my hair in a bun. I was as awkward and covered up as one can be at 13. Somehow, then, I was on my back, and he was heavy on top in his own blue shirt with a name tag, Ron, in stitched cursive. He had just come from work.

“I would love to go down on you,” he said between my tears and pleading.

Would she go down on you in a theater? I heard in a flash, as my body turned impossibly hot and cold all at once. As my body turned impossibly dense and hollow all at once. As my body froze and took flight, impossibly, all at once . . .

I cried, whimpered, begged him to please please please leave. His weight got heavier.

And then . . . he started to cry too. Nothing else was going to happen, I could tell. He started apologizing, still heavy on top of me.

I’m sorry, he said.

He was surely broken too.

He left the room eventually. I don’t remember how long he held me down on that bed, I don’t remember the color of the comforter or the sheets if maybe I didn’t even have a comforter. I don’t remember that, but I do remember the weight of him, and those eight words.

But I pretended I didn’t. I announced to Ron that I would be telling my mom what happened, checking to see if he would maybe kill me, or force me on the bed again, and when he didn’t, when he was defeated and nodded, I took my 13-year-old indignation and I readied myself for when Mom would return home.

She ended up calling first, from a pay phone at an outlet mall where she had been on a group bus outing doing some discount Christmas shopping. “You need to come home,” I said. I double-checked with Ron, who was just standing there, to see if he’d maybe pull out a gun or choke me to death and when he still didn’t, I mitigated: “Ron told me he wanted to lay me.” I cannot recall how much, if anything, more I shared.

Getting laid was a term I knew. It was a sex term a 13-year-old knew. I didn’t know the real meaning of “going down” and so I changed it to this.

Mom was silent and my heart was about to explode out of my chest with Ron standing in the room, and he actually had the audacity to say, “Well, that’s not what I said.”

Mom’s silence turned to panic. I don’t remember exactly what she said — something about if I was OK, if I was safe, that she will be home soon. Peanut, peanut, peanut . . . Her nickname for me.

•

Jagged Little Pill was an album that came out just in time for me to find a place of identification with it. I felt, even at ten years old, deeply understood by Alanis’s frenetic yet angelic phrasing, opening my mouth as big as I could match her volume and our pain. I had no language for feminism, but I knew gender mattered when Alanis accused the men in her life of taking her for a joke, treating her like a child. I was an overachiever at school who understood the pressure of a perfectionist, asking herself “how long before you screw it up?” I had never been in love, but I knew someday I would feel as romantic as she did, falling “head over feet” for a lover who must’ve treated her better than the one from “You Oughta Know.” And I knew that, someday, I’d probably feel as wrathful as she did in that song too.

I loved that she dressed in baggy button-up shirts and pleather pants. I loved her long face and long hair. I loved the music videos she made and her cameo in Dogma. I loved talking to people about the hidden track on her album, how it was a song about cheating, surmising that when she said she “played his Johnny,” she meant a Johnny Cash record. I felt deeply and urgently on the precipice of a kind of settling into my own skin. I was, with each play of that album, becoming alternative. And more importantly, an alternative girl. In the 90s. And when that door cracked open, it meant access to the edges of Riot Grrrl and lesbians and witches and zines, and everything that is punk and feminist and holy.

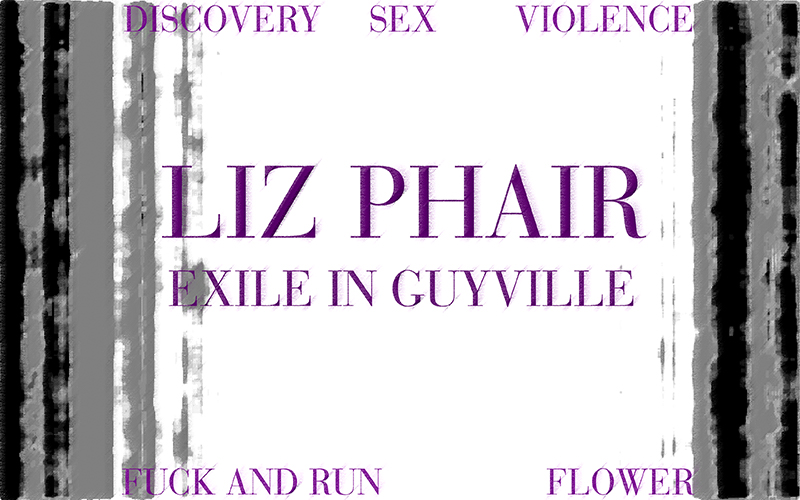

It also meant access to Liz Phair, which happened a bit out of order. Phair’s ineffable Exile in Guyville was released in 1993, two years before Jagged Little Pill, but I found Guyville in the used bin at Coconuts just a few months after getting into Alanis. It was just as exciting, albeit in a slightly more subdued way. Liz was growlier and less inclined to yell, a little more sad. A little more indie, I decided with all my pre-teen insight. She, like Alanis, also sang about sex, and I was equally warm and curious when hearing her lyrics about things I knew were probably too old for me. In “Fuck and Run,” Phair laments about being used for sex, even when she was 17. (Even when she was 12.) In “Flower,” there are fewer clean lines than “dirty” ones, and I pulsed with every single word. “Every time I see your face, I get all wet between my legs / every time you pass me by, I heave a sigh of pain,” she begins, and also: “Every time I see your face I think of things unpure, unchaste / I want to fuck you like a dog, I’ll take you home and make you like it.” She shares later that she wants this person’s “fresh young jimmy jamming, slamming, ramming” in her, and also that she’ll be his “blow job queen.”

These albums, coupled with the Drew Barrymore and Winona Ryder movies that I loved watching, were my earliest forms of sex education. Many of these pop cultural portrayals taught me that sex was both passionate and painful. Alanis is singing about sex acts that her ex-lover is now sharing with someone else; and she’s not happy about it. In “Fuck and Run,” Liz tells us that she wants “a boyfriend,” and not someone who leaves immediately after cumming. I learned it: men are dogs, but we love them anyway. We are so susceptible in our young and mature brains alike, to let these narratives seep into us, but we are at the same time, I think, so determined to prove them wrong.

I found a counter-narrative in Liz’s “Flower,” although I’d read as an adult that the song is more ironic than I’d initially interpreted. At face value, though, “Flower” is a beautifully sex-positive song that showcases a woman’s primal urge for hot, dirty sex.

As I climbed slowly into womanhood, I longed for both of these experiences. Heartbreak and pleasure. Heartbreak as pleasure, and pleasure as the reason for heartbreak. I thought it’d all be at the hands of men, but I would learn later that women (and people who didn’t fit inside either binary gender) would also bring me love, romance, orgasms, violent anger, and deep crushing sadness.

In any case, Liz and Alanis were my primer. Early lessons in my personal sexual discovery, preliminary models of women who fucked and were happy about it, and also women who fucked and were broken about it.

•

My assault didn’t fit into any of those boxes. Ron did not break my heart; he never had it. I didn’t want him, not one tiny part of me wanted him; I was, every inch of me, repulsed by him. And yet his was the first body on top of mine. His voice the first to utter anything sexual to me. He took the words of my alternative-girl-power-role-model, and turned them into a scourge against me.

It is one of the most egregious aftermaths of sexual violence: the linkage between what is meant to be a pleasurable experience coupled with the experience of harm and trauma. Cultural theorist Stuart Hall used the term “articulation” to describe two things that become unified through “structured relations of dominance and subordination.” More simply, these are things that we see and hear in culture and media that we presume are natural pairs, when really they are socially constructed. Sometimes this emerges rather innocuously (e.g. “blonde + cheerleader”), sometimes racistly (e.g., “Black + poor”), sometimes stereotypically (e.g. “Christian + conservative”). I think about “sexual + violence” as an articulation, in that we accept the terms of the pairing at all. For me, though, there was nothing sexual about what happened in my bedroom that night. Even though sex words were uttered, and sex positions were assumed, it wasn’t anything like Liz described wanting so badly, it wasn’t anything like something Alanis would be sad she lost. I imagine many victims of sexual violence feel the same. And yet, we keep hearing it: “sexual” alongside what is really just plain-old violence.

How could I possibly reconcile the excitement of early sexuality with a simultaneous desecration of it? How could I possibly heal?

•

I am grateful to say that Alanis never became unlistenable. Which isn’t to say that everytime I hear “You Oughta Know” that I don’t remember (I do). But to say that the intense satisfaction I got from that album, including the sex parts, outweighed the event for which they’d become remnant. And Liz too, so interwoven with that time period via my CD case and the 1995 concert I saw her and Alanis perform, remained salvaged.

My first #MeToo moment was traumatic, to be sure, but I feel lucky that it didn’t deter me from sex. And I think both Alanis and Liz are partly to thank for that. I learned, before the incident, that admirable women were also sexual beings. And I wanted to be that too. I didn’t want Ron to take that from me. I didn’t let him.

I began a process of unlinking sexual violence from sex. I was lucky to end up with a handful of tender, consent-centric young men throughout high school, and we learned together how to explore our bodies in ways that felt good and kind. And when I got to college and had experiences that were more murky, I at least knew the difference between what felt good and what didn’t.

Not all experiences of sexual violence are so easily de-linked. For many people, sexaul assault and rape occur after an initial feeling of desire and pleasure for and with another person; this is known as intimate partner violence. I don’t mean to speak for those experiences, in which the blurring between sex and sexual violence is much more complicated. But for those of us who experienced assault without any grey area, it feels important to de-couple these terms.

Similarly complicated is the role of BDSM and kink play in the process of healing for many survivors of sexual abuse, assault, and violence. As someone who has personally found deep healing (and pleasure!) in kink dynamics, including acts of physical “violence” (slapping, choking, restraint, etc.), I had to do a lot of reflecting on the root of this desire. Was it a pathological result of a traumatic incident? Was it a perfectly human impulse, stigmatized only because of a puritanical society? Ultimately I concluded that it didn’t matter because I realized that violence was a lack of consent, but pain could be invited and enjoyed.

Like Liz who was near-desperate for “jamming, slamming, [and] ramming”, heaving sighs of pain while at the same time wet and wanting, I found peace in the warm wash of hurting when I asked for it.

•

Shortly after the incident, Mom and I left Ron’s house for good. I kept quiet about what happened for years, but then slowly began sharing it with partners, close friends, finally a therapist, and then eventually wrote about it publicly. The years I was silent were years of layering, shoving down trauma, and pretending that breathing problems, hair loss, and a persistent eating disorder had nothing to do with what happened that night (or the many uncomfortable incidents involving Ron before that). It took me until I was 30 to finally recognize those aspects of my adolescence as “traumatic,” when a therapist diagnosed the erratic behavior I’d recently been enacting in my relationships as symptoms of C-PTSD. That was the beginning of the most painful, self-reflective period of my life. Finally, being honest about your past is a liberating horror.

•

I still have Alanis and Liz on a steady rotation. I know I’m not the only one, given the steadfast popularity of both artists, including what was supposed to be their upcoming almost-sold-out tour with Garbage. Undoubtedly, whenever they are eventually able to do the tour, there will be swarms of elder millennials reliving those formative years of finding and falling in love with alternative women in music.

I sing along to both Exile in Guyville and Jagged Little Pill in their entirety. I don’t skip “You Oughta Know,” although sometimes I skip singing that line. I have decided, though, to preserve the albums as reminders of when I was finding my strength as a burgeoning woman, rather than the moment I felt most powerless as one. And I have found solace and new meaning in the songs as I have experiences to match. I was right at 10 years old to believe that I would eventually find romance to match “Head Over Feet,” lust to match “Flower,” and experiences of sexism in the workplace to match “Right Through You.” And when I was brutally cheated on when I was 24, I had the bittersweet realization that I could finally have a new — and more appurtenant — connection to Alanis’s anthemic song about a lover scorned.

•

Alanis and Liz taught me about what sex was and what it wasn’t. I can’t imagine navigating the difficulty of “sexual” violence — or the pleasures of sexual becoming — without them. •