If I were to use two words to try and encapsulate what it was like for me to grow up, by which I mean, the passions I most often enmeshed myself in — not how much I was loved, or anything like that — I would opt for “books” and “woods.”

When I think of how many other factors there were in my own particular tapestry of childhood, these two worlds, paradoxically, only seem to stand out more, attesting to the sway they had over me.

I played sports regularly and vigorously, especially hockey, with many far-flung early morning trips to rinks over various parts of New England. My father pulled our car into the closest Dunkin’ Donuts so that he could get a large coffee and, in turn, keep himself awake. I’d be barely conscious myself, but completely energized, naturally, after the game, especially if I had a productive one and potted a goal or two, and then you couldn’t stop me from talking.

Not just about hockey, but my recent thoughts, things I was reading, 19th-century coins I had lately learned about which I was keeping an eye on at a local coin shop, adjacent to a village green that suggested to my young mind— for, as I said, I was an ever-eager reader — a curiosity shop in the fictions of Charles Dickens, and that we were less residents of New England than Merry Olde itself.

I didn’t like to let too many moments of silence pass. I didn’t know it then, but this was part of one of many processes for me of becoming a writer, someone who tells stories for an audience. The audience was technically this one person, my dad. I had it somewhere in my mind that I wished whatever I was saying to be interesting to others, had they been jammed into the backseat and propped up with coffees of their own, open to hearing some anecdotes and tales and what for me passed as deep meditations and dilations if they were compelling enough.

Our yard was carved out of woods. When my parents decided to move to this town, before they adopted me, the land of our development was just forest. I remember later my mother telling me how she and my dad walked out a mile or so, twigs and leaves crunching underfoot, with no paths, to arrive at a roped-off plot, where our modest house was to be built, with my mom freaking out over the surfeit of snakes everywhere. It was like some real Dagobah environs, only much drier.

One person’s terror, though, is another’s idea of a romantic place, what I call an away-space, because no matter how often we were there, it was never enough, never felt as though we possessed it as it possessed us. When she told me that story years after we had left what I viewed as our original and abiding town, a sort of civic North Star, I was nostalgic and sad. We might as well have lived beside an enchanted glen, so far as I was concerned, and, in a way, in my mind, which probably matters more, we did. Not my mind, obviously, accounting for what matters more; a mind, the gathering pool each of us have within, where all currents can be overcome — and where possibility is not tethered to standard rules of temporality, and what you can give to yourself and do for yourself counts for a lot more than what anyone else who is not you might provide in the external world. Nice and needed though those things can be.

I spent a lot of time in those woods, which went back for miles, after the houses of our development had been erected on roughly rectangular parcels of land. I marked paths by breaking small branches, waded in a brook where crayfish and snapping turtles — the punk roués of the small stream ecosystem — went about their days. I saw black racers haul ass — if asses they had — after mice, and once I even thought I saw a copperhead, though I had no one there to confirm this with me, and my little nature books said that none lived in these parts. The copperhead chased no mice, but rather just stuck its head out from under some desiccated beech leaves that had fallen from the tree above, as if the snake had been waiting for some cover to descend like softly falling calico snow to match, more or less, its russet scales. It struck me as the perfect autumn snake, and I was glad I was not a vole passing by at ground level.

It seemed like everything we did was done outside. Street hockey, games of flashlight tag, intense backyard baseball series for the highest of stakes when you are that age — bragging rights — and whatever someone else might think up next. Which is why it seems a little incongruous that something that shaped me, I now realize, as both a thinker and a person — and even a burgeoning artist — took place indoors, in my family’s basement.

I’m not a big computer game person. As an adult, as I make my dizzying — oft-depressing — tour of dating sites, in my search for someone brilliant, dynamic, surprising — eh, we all want what we want — I’m taken aback by the number of my fellow adults who play a lot of video games. True, I’d rather you do this as one of your daily pursuits than contact me with a “hi LOL” that causes a little bit more of my soul to leak out of me and congeal on the floor, or solely inquire as to what oil I prefer to cook with, especially as I do not know that people cook with oils and have no clue or interest that it matters very much which one you select.

But it’s weird to picture someone 30-years-old sitting there, “gaming,” after a day of working at the hospital, the law firm, the school. Not that I’m expecting them to lug out another translation of War and Peace to continue on in their evaluative comparison of which is best. (“Suck it, Constance Garnett! Props to you, Pevear and Volokhonsky!”) But, like, Mario Kart? Those brothers are still around? Obviously Fortnite. You hear about that so much that even someone like myself, who has no clue, exactly, what it is, knows the kind of thing it is.

It’s usually around this point — and I have this apperceptive reaction repeatedly — that I realize I’m being somewhat hypocritical. Because for all of the books I read, all of the forest I explored, all of the hockey games I partook, if we’re talking proper nouns, little did more for me in my childhood than a computer game called King’s Quest whose mere mention sends me back to rolling greenswards that never actually existed, but from which I learned that important waters can be added to that vernal pool inside of all of us, which in turn can flow back out into the world in such a way that we are truly joining it, at the level of who we are. Or, if you are an artist, at the level of that which you might make.

King’s Quest came out in 1984, a time when it felt like you barely had a computer. It was this new-fangled concept, almost as if it was surprising that it was even an option to possess such a contraption in the place where you lived. That option, it felt, came not long after the option to have cable TV. I remember, for the latter, this person knocked on our door — he actually walked door to door — trying to sell people on this cable thing, and when he started mentioning the Disney Channel and also a sports channel that televised hockey games, I was like, “Sold! Let’s do this!” — not that it was my call. But it worked out okay. Before that basement was furnished, I learned to shoot a wrist shot down there, and if a plastic street hockey puck could make a dent in cement walls, or even pass through them, on account of having hit them a specified and cosmically ordained number of times, doubtless I would have hit the mark. As it were, I just broke a lot of windows in the window wells above, which could bring down any of a number of animals from outside into the basement — the aforesaid vole, a garter snake, a baby owl — depending on whom — what — was occupying that sunken space at the time. I was a despoiler of animal timeshares.

The basement was largely reserved for rainy days after it was furnished. That must have been how my friends and I came to be playing King’s Quest on my family’s Apple IIe computer. What a hunk of machinery that was. There were cannonballs sunk into the ground outside of our local library, and I thought how you might sink this computer there, too. It was back-weighted so that you tipped forward if you lifted it, something I didn’t reprise after a first attempt. I’m not sure anyone plays King’s Quest now. Perhaps ironically? Or there must be vintage computer game zealots out there who are into this kind of thing.

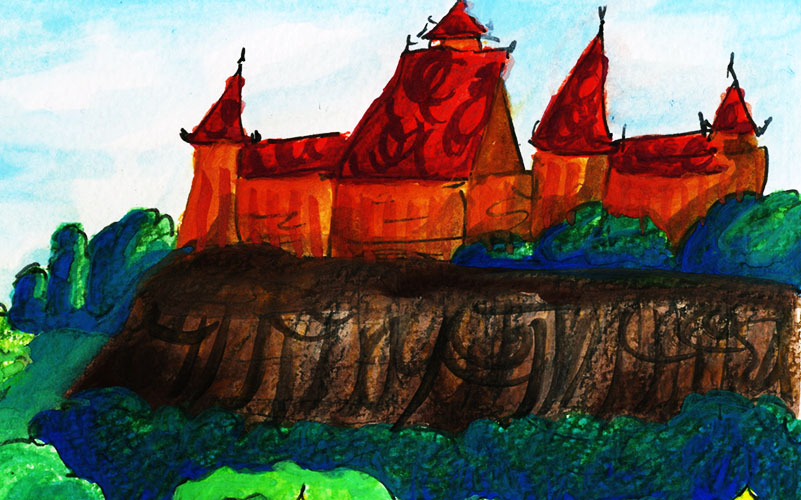

Basically, this is the setup. You play the part of Sir Graham. He was originally named Sir Grahame, which probably had the same pronunciation, but which I bet a lot of kids rendered as gra-HAME, as if that last syllable wanted to yell at you. He had a jaunty feather in his cap and looked like some carefree Medieval groundskeeper with an eye on quaffing some flagons of the local porter later in the day at a nearby inn. This was a little confusing, as the packaging clearly stated that he was the greatest of all knights in a land called Daventry, but he wore no armor, and he might as well as have a blade of digitized green grass in his teeth. He kind of seemed a Middle Ages version of a rube. But it was on account of his rep as a knight that he was being summoned to the king, as Daventry was in debt and so the king needed quick cash. Kind of shady. The king has heard that there are three priceless treasures scattered in the vast surrounding forests, so Sir Graham should get himself out into those wealds, find the loot, and come back so the king can sell all of it and restore peace and harmony and good credit to the land.

I know the graphics look crude now. I would imagine that most kids would laugh at them. The thing was, kids weren’t that much different then. It’s not like they believed the animation for Pacman and Pitfall Harry was awe-inspiring. You knew it was rubbish and limited, and you accepted this, even as you laughed, and for what deficiencies in realism and quality there were, you had your imagination to span the chasm. Your mind was the gap-bridger.

For me, my mind’s eye performed this service. I like Medieval stuff. Things from early England. I can watch Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland in 1938’s The Adventures of Robin Hood on a loop. There just seems to have been so much green during that time, and who doesn’t like castles and moats and legends that were a hell of a lot harder to disprove back then. Dragons? Well, maybe. Fairies? They seem likely enough. Tough to spot, who’s to say? Forest ghosts? I could totally see that, even if you can’t see them. Elusiveness seemed central or having a cave, which likely also abetted in the former.

Even as a kid, I never liked to have my thoughts dictated for me. Sounds like a non-sequitur or syntax gone awry, but you understand the difference; some people like to be thought for, and others like to think for themselves, and then corrected, or focused on self-correcting, as need be — if there be any need — with the stockpiling of facts and viewpoints. When you are this way, you move between external and internal realms in a fashion that what occurs in the world outside of you can be brought inside your head for restructuring. For new possibilities. For instance, outside in the world, we can only, say, climb so many steps, or chop so many logs of wood, per minute. You are at the mercy of the space-time continuum. Rules of physics. But in your head, there is nothing to say that you couldn’t write three books in five seconds. It’s not technically impossible. What you create there, divorced from a space-time continuum, can then go out into the external world. Or part of it can.

There was something gripping and thematically telling for me about being inside, playing King’s Quest, and feeling that I was in a boundless world, not a crappy basement. I was pulling that external world into me, which was affording me insight into my inner one. Boy, did we love that game. It was on floppy disks, and it felt like there were 1 of them, each two-sided, but that couldn’t have been nearly the case. You saw this magical land through the eyes of Sir Graham. You were he. And you didn’t really get this with other computer games.

For instance, Oregon Trail. Everyone played that at school, and I was recently crestfallen upon asking a precocious 14-year-old neighbor of mine if she knew the game, only to receive a sad, side-to-side shake of her head in the negative, that at least made me feel like she thought she could have missed out on something cool. There was likely some excitement in my voice, so I am not sure how untainted my results were. Oregon Trail, though, was about little you saw on the screen. You didn’t care about that. It didn’t feel like you were actually journeying West, it doesn’t matter what level of imagination you have. It felt like you were trying not to have your computer family die of the shits, or starvation, or by having had their wagon tumble into a river. (Did that really happen that often?) It was a little like a Choose Your Own Adventure book in how willy-nilly it could be. Being good at Oregon Trail was like being good at Crazy Eights, but it was decently educational, in theory, so school systems liked it, in that manner in the 1980s that parents believed fruit juice and lots of it was good for their kids, because it had the word “fruit” in it, sugar be damned.

King’s Quest immersed you. If you watch a film like Citizen Kane, you’ll note the depth of field, such that it looks like you are being pulled into the screen, or that you could walk into it as if it were this beckoning imagistic pathway primed for your explorations. You didn’t even necessarily have to hang out with the characters on the screen. You could take a hard left and see what there was for you to find if Charlie Kane didn’t compel you enough. That was how King’s Quest was designed as we walk not only with, but as, Sir Graham. You hit the side of each screen, which depicted a different place of a highly eclectic forest, and what you’d often have to do is pop in another disc, wait for the next screen to load. Bated breath for my friends and me. You did not know what you’d next behold. The limits of clunky graphics were left behind awfully fast, as you internalized this world more and more, seeing it less with your eyes, than with your mind’s eye. It absolutely blew our minds the first time we moved Sir Graham about such that he passed behind a tree, and you couldn’t see him until he sauntered out the other side. Sounds like nothing, right? This was a huge deal in terms of computer game animation. For the player, it was tantamount to a form of magic, even if you still realized that you were looking at shoddy graphics of fields and lakes that might as well have been designed by your clever, tech-friendly math teacher his leisure hours. You typed in commands, which was your way of retrieving, say, a dagger in a hollow stump, or befriending an elf who, for no other reason than that he liked how polite you were upon your approach — you had the sense that most people tried to kill him, so this was a low bar — forked over a magical ring that could turn you invisible: but just once. Choose wisely.

We minded that we had to wait for new scenes to load, but minded in the sense of a child at Christmas who is told to not open their next present until their sibling has unwrapped another of theirs. Delicious anticipation. It was as if all of those woods outside of our house had been dipped in some fairy brew, all of their concomitant wonder — but even more of it is, like a bonus pack had been affixed — and crammed into the hard drive of this Apple IIe courtesy of these talismanic floppy discs.

I like how the game’s designers ripped things off. Let us call it, apportioned. For example, there included a woodcutter and his wife, who were clearly based on the parents in Hansel and Gretel. Cinderella’s Fairy Godmother turned up. There was a giant rat who we had a hell of a time trying to get past, as he guarded treasure in an underground cave. There was some command you were supposed to use after you had plied him with something — magical cheese or whatnot — but we could never figure that out. We would sit there — or, rather, jolt up from our seats, torquing our bodies as if moving certain ways would allow Sir Graham to do the same — in an attempt to get our knight past this Kafka-esque gatekeeper, simply by juking him and racing around the side. Of course, computer games don’t work this way. We were basically counting on a flaw in the design, a programming loophole that we might dive through, say, once after trying 250 times. And try we did — more than 250 times, uttering probably our first out-loud curses, the rain pattering outside, sweat beads gathering on foreheads, saying, ‘I give up, you try it this time,” or “God you suck at getting past this rat, let me bleeping do this,” only to watch Sir Graham perish yet again, all but being able to hear this digital doppelgänger of ourselves shout back, “Boys! This is not the way! Find a better way!”

Eventually, we found the loophole. Brows became dried. We scrunched them as we debated how to handle the next quagmire, which I believe once involved an actual quagmire, or maybe that was King’s Quest II. For there was a whole series of these games after the first version proved so popular. They got loopier and loopier. Dracula was in King’s Quest II. One time I was playing by myself and Dracula was dead. Or he had left. Anyway, I had his castle to myself. That’s kind of bitching, right? I was so into horror films ever since first seeing 1931’s Dracula with Bela Lugosi as the Count. I had plastic fangs and a cape when I was younger, and this empty box at the bottom of my bed — I think toys were supposed to go in there, but the Star Wars stuff was always scattered about — so I thought, what the hey, this can be my vampire coffin, so I’d lie there, waiting for, well, I’m not sure what I was waiting for. Van Helsing? Inspiration? A bride? My friend to get home from the doctor’s so we could throw a football around? That was kid stuff, I thought, as I played King’s Quest. You find in life that you say “that was kid’s stuff” an awful lot, that a part of you never really stops saying it because in some ways kid stuff is adult stuff and vice versa. What I mean by that is that both adults and children require games and exercises of the imagination, and those are not age-specific games, because any thoughts may arise from that activity. It’s like your brain is going for a run or lifting some weights. What matters about the activity is what can be done as a result of it, subsequently. When you are in fine fettle. When you are in shape for that which you wish to do. The mind is the same way. What it might become in-shape for — or have need to become in-shape for — is to paint better if you’re an artist. Come up with new stories for your novels if you’re a writer. Get better at self-awareness, if you’re anyone.

This is one reason why I think those rainy afternoons of playing King’s Quest has never left me. And when I found myself alone in Dracula’s castle, I, as Sir Graham, walked into Dracula’s basement, located his earth box, and typed in the command “Get into coffin.” You couldn’t just say anything and get a response from the game. You couldn’t say, “I’m ready, blow me, King’s Quest.” There were only so many word combos that worked. I didn’t expect this one to draw any reply, save whatever the game’s go-to response was for “does not compute.” Shockingly, the game remonstrated me with something like, “No, what’s wrong with you? Why would you wish to do that?”

I told no one of this, and, yes, it made me think there was something the making of elves or sprites going on here. I liked meeting Rumpelstiltskin in the original King’s Quest, because I had read his case history in some of the first fairy tales I had encountered. To see him reposited this way was freeing as someone who, even then, knew he wished to write, that he would write, that he had to write. I realized that you could dislocate characters from where you had first associated them. Flannery O’Connor would call this displacing a person, and life is often a series of displacements. Why should this be different for characters in a story? I had no clue what Rumpelstiltskin might have experienced to have ended up here, for the time being. Maybe someone else had guessed his name and he’d been shot into computers across America for a purgatory period. Maybe it was a gig he took to round out the rent. Maybe he had cloned himself. You could account for this strand of his narrative. To do so meant that you had to be able to make a narrative yourself.

Now, this is silly, in a sense. I realize it was some people sitting in a room thinking what characters were in the public domain that they could slap into this kid’s computer game that surely had more interest to its designers because of the new forms of animation it used over any narrative cohesion or depth. But that’s not how I saw it. I believe we acquired some beans from Rumpelstiltskin, which meant, naturally, a beanstalk was in our future and a Giant. Ah, another problem to deal with. I recall that we couldn’t figure out him either, much like with our giant rat situation, and it was harder to find the loophole up in the air, atop a vine leaf, which meant that as we cursed this time, and all of those times, we watched Sir Graham — and thus ourselves — plummet to the earth, but we’re at least spared the sight of his, and our, implosion.

But we always made him get off the mat, so to speak, and resume his quest. Eventually, as the rains outside dissipated, his spell on us would be broken for that day, and we would ascend from the basement to head out into the woods, curious what animals would be first out after the showers. Mourning doves seemed to prefer this moment, as though they were petrichor buffs. Maybe it’s a dove thing. As I looked over that backyard world, felt the water from the grass starting to leak through my cheap tennis shoes, it felt more than it had before like one I could breathe into me, upon which if I worked enough, with proper care and imagination, I could exhale back out again, and these breaths from my soul, that kind of autumnal breath you can see, would be things I called books and stories.

I never found the three treasures the king had banked his future upon, so in the grand scheme of Daventry and what ails its leading resident, I was something of a letdown there. Maybe they had to sell the place. Maybe a developer turned it into a Medieval-themed amusement park, and put the rat, the elf, the giant, on the payroll. But I had a better understanding of a different quest. That is a compliment worthy of the most revered knight in all of the land. Ideally, my Sir Graham, on his own — after we had departed for that day — was able to complete his own personal mission, perhaps while uttering, “Finally, those kids are gone, and I can get this done right. Ho, Daventry!” I’ll continue to think of him that way, questing. •