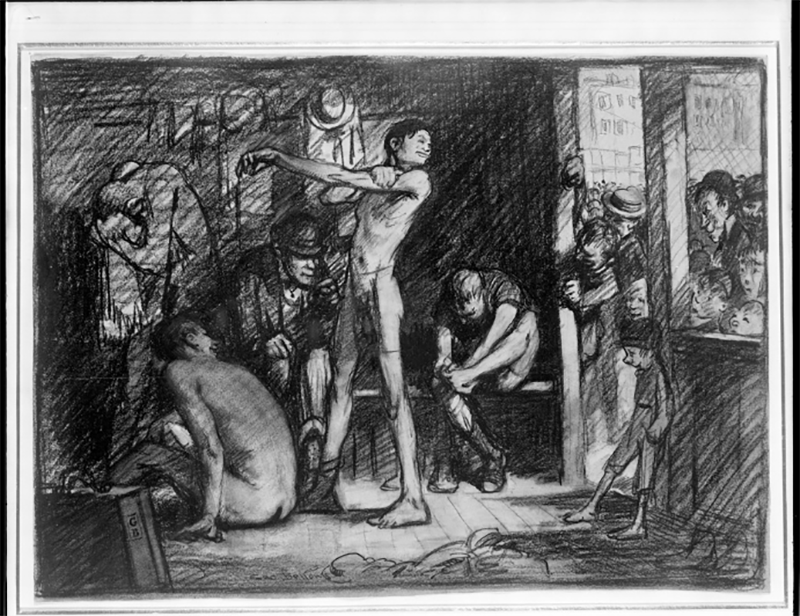

The image is a black-and-white, lithographic crayon drawing, and it resides in Harvard’s Fogg Museum of American Art, an image of three men in various stages of dress in what appears to be the corner of a wooden shed or perhaps a barn. In the right background, seated in a darkened corner of the shed is a man, wearing only a shirt, leaning forward and pulling on his left sock. Even more shadowy and obscured are three men on the left of the drawing — one standing and apparently toweling off his face; another, nude and seated on the planked floor with his back to the painter; and a third, a baronial older man in derby and jacket, seated on the bench in the hazy background. You would likely not recognize it as an image of small-town, turn-of-the-century baseball but for its title: Sweeney, the Idol of the Fans, Had Hit a Home Run.

It is a post-game scene. Your attention in the image is directed toward Sweeney, whom the artist has placed in the center of the drawing. The nude Sweeney is cast in the light of the room’s open doorway, and he stands a few feet from the door with his left arm outstretched in front of him, while he flexes and massages his left tricep with his right hand. Sweeney is looking over his left shoulder toward the open doorway, where a crowd, apparently having followed their hero to this makeshift dressing room, clamor for a glimpse of Sweeney, the idol of the fans. Sweeney has a confident, almost arrogant smile on his face — “Take a good look at your hero!” he seems to be saying to the throng. And just behind Sweeney, probably hanging on a nail, are a bright, white jacket and hat, suggesting that Sweeney’s clothes match his post-game confidence.

Sweeney is significant for two reasons: first, despite the fact that Sweeney may not depict an image that is immediately recognizable as a baseball (or baseball-related) context, the artist, George Wesley Bellows, is one of the few historically significant American artists noted for depictions of sporting scenes. Bellows offers only some depictions of baseball — an obscure oil painting and several black and white renderings — but his observations on sport can be found most famously in his New York City boxing scenes: Dempsey and Firpo, Stag at Sharkey’s , and Both Members of this Club. And Bellows offers, too, treatments of more highbrow sports, as in Polo at Lakewood and Tennis.

Second, Bellows’s artistic perspective on sports was derived from a deep and lifelong association with baseball, and his rendering of sporting scenes reflects a perspective that might only come from an artist who has looked at athletics from both sides.

George Bellows was born into a household of wealth, political conservatism, and pious Methodism in Columbus, Ohio, in 1882. He was a born artist, according to biographer Charles Morgan — intelligent, meticulous, and somewhat aloof, and as a youngster, he would sit on the porches of the girls in his school and turn out drawings for them. But by early adolescence, Bellows was drawn in two directions: despite his talent and passion for art, he was determined to pursue baseball. Morgan suggests that Bellows’s decision to play baseball was, in effect, a declaration of independence from his doting mother. “The National Game,” writes Morgan, “would equip George to become the painter of the nation.”

Whether or not Bellows ever achieved such status as a painter is moot. And while Bellows’s forays into baseball as a subject were limited, there is no question that baseball was the defining avocation of his life. By the age of ten, Bellows plaintively begged his way onto a local team and served as its scorekeeper, and for five years, he kept score, had a catch with any willing partner, and, finally, found himself in the lineup as a right fielder (owing to a teammate’s case of chicken pox.)

Working against Bellows, however, was a less than imposing physique and a slow-to-develop athletic coordination. Not until late in high school did he come into his own as an athlete. In his senior year, he played a solid shortstop and attracted the notice of professional scouts, including, according to Morgan, the Western League’s Indianapolis team, who hoped to entice him to “plug the hole at short.”

Bellows, despite at least one professional baseball offer, enrolled at Ohio State University. Unfortunately, Ohio State did not enhance his skills as a visual artist. Bellows’s college career, though, profiles a young man with a Renaissance breadth of interest — coursework in Greek art, athletics, glee club, illustrations for campus publications. His college career ended early at a professional crossroads: he had stashed away money earned playing semi-pro baseball, and, although professional baseball did not hold much interest for him, indeed, the Cincinnati Reds pursued him earnestly. Instead, he moved to New York City to paint.

Bellows spent the next 20 years studying, defining himself as an artist, and articulating the role of art in life. But in the background always was baseball. He studied under and would become a pupil of Robert Henri at the New York School of Art — and he played baseball. He played for the semipro Brooklyn Howards, but as several sources note, he was a self-acknowledged, weak-hitting middle infielder.

For Bellows, baseball was a tonic for feelings of boredom with painting. But, as athletes come to appreciate, the body becomes less forgiving with age. “Having become rather dull with the brush as you may judge” Bellows wrote his wife Emma, “I joined the baseball game today. . . Well, I had a barrel of fun after hitting a three bagger I turned third on the slippery grass and twisted my bum knee again. So I’m afraid there’s no more baseball in me this year.”

In 1924, when Bellows was in his early 40s, he was still playing spirited ball, but age — abetted by poor diet, weight, and a smoking habit — had further gained on him. He knocked himself unconscious on an attempted steal of second, and later that summer, he felt a pain in his midsection as he broke for an infield fly. And midsummer, Bellows was admonished by his physician to change his lifestyle — but it was too late.

Having lived a short, almost demonically driven, life, Bellows died in 1925 at age 42 from appendicitis.

Despite his 600+ oil paintings — his portraits, his seascapes, his grimy urban scenes — Bellows is most popularly recalled for his boxing scenes. Indeed, in many shopping mall art shops, in the bin labeled “Sports,” you will find the ubiquitous image of Luis Angel Firpo sending Jack Dempsey tumbling backward through the ropes and into the crowd. Take a look in the lower left corner. There is an oddly-oriented, balding head. Bellows has placed himself in the scene. And this curio, I believe, suggests in a small way that Bellows saw his spectators as important to his scenes as his athlete subjects.

Despite a private life defined by baseball, Bellows left few images of the game. Interestingly, two of them feature impassioned fans. Joel Zoss and John Bowman, in their fine multidisciplinary study of the history of baseball, Diamonds in the Rough, trace the appearance and disappearance of two Bellows sketches entitled Kill the Umpire. As with Sweeney, the scene in Kill the Umpire might not announce itself as a baseball setting but for its title (which, apparently, was retitled The Great American Game when it appeared in 1914 in Harper’s Weekly).

Bellows’s Kill the Umpire clearly is a stadium scene, and it is a scene familiar to fans who have sat in the vicinity of a drunken bunch. The scene doesn’t really suggest the contagion of its title, for not all the fans seem to share the mob violence sentiment. In the center of the spread are the ringleaders, a raucous few who seem to want to incite the crowd. But just a few rows in front are a curious and somewhat agitated couple of fans who are turning around to find the source of the commotion.

The crowds in Bellows’s sporting images, while typically not central to the scene, are integral to understanding the event. In one of his more famous early prints, Both Members of This Club, Bellows makes a powerful social statement. Public boxing exhibitions in 1909 New York City were illegal, but private clubs could grant temporary “membership” for one evening to two fighters who, as members of the club, could enter the ring. The images of the fans in this painting are grotesque and ghoulish. Bellows studied the sport closely, and nearly all of his boxing images are from the perspective of ringside seats, Both Members of This Club, it has been argued, suggests Bellows’s contempt for the ostensible membership of the fighters and the probity of its true members.

Back to Sweeney. Look closely and you will see more than a hero and his adoring fans. It is an image that might best have been rendered by an observer intimate with the game. Sweeney is the idol of the fans, to be sure, but his supporting cast is carefully nuanced. The shadowy but well-dressed man in the background is likely an owner (or a financial backer of a semi-pro team), his visage turned toward Sweeney. We can’t see his face, but we can be fairly sure that he is very pleased with Sweeney’s performance and — more importantly — his ticket-buying following. Sweeney’s teammates, however, do not appear to be caught up in the moment. They pay no attention to the fans, to the owner, or to Sweeney. In fact, they probably see this same post-game show whenever they play. They just get dressed, collect their ten bucks and head home.

There is a Sweeney on every baseball team. Several decades ago, I worked in the visitors’ clubhouse of a Major League team, and as players, media, and fans understand, the one place that is off limits to all but players is the trainer’s room. The media respect this boundary, but, from time to time, stars (and stars du jour) exploit the imaginary line. I recall on several occasions players showering, wrapping a towel around their waist, and standing just inside the open door of the trainer’s room for no other reason than to make the beat reporters wait and wait and wait.

I see the same interaction in Sweeney. The hero strips and showers and flexes for his fans. Eventually, he’ll emerge, but on his own arrogant terms.

Bellows was a ballplayer-turned-artist. Billy Sunday was a ballplayer-turned-evangelist, and it could reasonably be argued that both were the most significant figures in their respective fields in the first 20 years of the 20th century. And Bellows chose Sunday as a subject for several of his drawings – not out of admiration but because Bellows “casually detested Billy Sunday.”

In The Sawdust Trail and Billy Sunday, Bellows presents Sunday at the center of a chaotic religious revival. The Sawdust Trail, set in Philadelphia, as a banner in the back of the tabernacle tells us, presents a revivalist, with his back to us, standing on a high platform, his arms outstretched as if he were a conductor preparing an orchestra or leading a choir. The composure of the revivalist stands in contrast to the chaos in the foreground, where congregants are gasping, fainting, and waving their arms in paroxysms of spiritual renewal.

Billy Sunday, however, is a more direct study of Billy Sunday and his histrionics. With a heavy fist, maybe clutching a Bible tucked under his left arm, he points a damning finger from his extended right arm toward the crowd. The Reverend Sunday, in profile, straddles two roughly hewn lecterns. It appears that he is about to leap from the pulpit into the throngs in the tabernacle to bring home his message. Indeed, he looks something like a Heisman Trophy.

In both renderings of religious revivalisms, Bellows again explores the relationship between “player” and “fans.” Sunday, the baseball player, the evangelist, the performer, in both scenes, controls and directs the energy of thousands of congregants. Sunday, to be sure, would be all but forgotten as a baseball player had he left sports for a career in the steel mills. But as we see in Bellows’s renderings of Sunday, it is his subject’s athleticism, his subject’s magnetism, his subject’s showmanship that command attention and fame.

Despite Bellows’s public contempt for Sunday, I believe that he chose Sunday as a subject not because of Sunday’s world-renown but because of his world-class talent. I don’t believe that Bellows profiled Sunday because he had been a baseball player, but, rather, because Sunday had been a professional athlete. Bellows recognized in his subject an arrogance, confidence, and egocentricity that define professional sports at the highest level.

Joyce Carol Oates describes Bellows as a driven man — indeed he completed 600 or so oil paintings in his lifetime. Oates further suggests that Bellows was the most famous American painter of his day.

I am not qualified to assess the technical skill or innovation that Bellows brought to American art, and while I am an enthusiast of his work beyond boxing and baseball and polo, I feel more than an aesthetic appreciation for Bellows’s sports imagery.

While I cannot claim to understand the artistic mind, I believe that we can see the vision of an athlete in Bellows’s baseball paintings — even when the subject is not the play on the field. In fact, while there is a significant body of baseball art that is evocative and enjoyable, the subject is often the player — not the crowd or the dank locker room or the batboy lingering inside the clubhouse door (another image in Sweeney). Too much baseball art carries the sappy sentiment of the endless game of catch with our fathers in the backyard.

A few years ago, I attended one of those hot-stove caravans that bring a few marginal big leaguers and maybe an announcer or two to the fringes of big league markets. During the post-meal Q and A, one of the fans asked the panel what their favorite baseball movie was. They all said Bull Durham, which, they agreed comes the closest to showing what minor league baseball is all about. And think about how many scenes take place behind the scenes in a minor league ballpark. It’s no coincidence that the director was a former farmhand. And, I believe, George Bellows looks at baseball through the same lens.

Morgan concludes his biography of Bellows with the assertion that, if Bellows had not pursued art as a profession, there would likely be a bust of him in Cooperstown. This strikes me more as naiveté than as hyperbole. There are few primary accounts of Bellow’s talents as a baseball player, and while his art and demeanor seem to project the requisite confidence of a world class talent, we’re all better off with his decision to forsake baseball for art. •

All images by Isabella Akhtarshenas. Painting courtesy of Fogg Museum at Harvard University.