Fashion is ephemeral, but there is one item of clothing that has been worn since Biblical times — a distinction that’s even more impressive considering it was intended to be uncomfortable. It’s the hair shirt, aka a cilice or sackcloth, made out of scratchy animal hair or coarse fabric. Primitive man probably wore clothing made of these itchy, stiff materials because they were the only ones available to him, but his more civilized descendants chose to wear hair shirts as penance for offending their no-nonsense god by sinning.

For instance, in the New Testament St. John the Baptist wore camel’s hair. Not the soft undercoat used in the camel’s hair coats we see today, but the outer, inflexible “guard hair.” Even Jesus, not given to sartorial commentary while preaching, was compelled to point out the difference to a crowd drawn by St. John: “What did you go out into the wilderness to behold? A reed shaken by the wind? Why then did you go out? To see a man clothed in soft raiment? Behold, those who wear soft raiment are in kings’ houses. Why then did you go out? To see a prophet? Yes, I tell you, and more than a prophet.” (Matthew 11:7,9)

As the website www.aleteia.org points out, St. John accessorized his sackcloth, “with a leather girdle fastened around his loins.” This is the same simple outfit worn by the prophet Elijah, as described in 2 Kings 1:8, which the Aleteia article cites. In this way, SJB serves as a link between the Old and New Testaments. Perhaps it also shows that even a saint is not above copying the outfit of a famous predecessor.

Among religious orders, the literature tells us, members often wore hair shirts beneath their cassocks and kept that fact to themselves until they died. Presumably, this practice cut down on feelings of itchier-and-holier than thou among other wearers of the shirts. Then the people who had lived with them might look back and recall times they noticed the deceased surreptitiously rubbing his back against a wall or post. And since the penitents wore the same shirt 24/7 and never washed it, cohabitants had to endure the undershirt’s odor — a secondhand penance of their own.

Today’s secular citizens must think religious penitents seeking bodily pain have something wrong with them. And these religious seekers of discomfort must think any irreligious person who suffers for fashion’s sake has mental issues of their own. Yet a review of the points of pain in fashion history suggests that dressing to fit in with the cowed crowd is often more important than how clothes fit and feel.

Consider Japan’s Heian Period (794-1185 A. D.), when the classic kimono was all the rage — though it was so restrictive it should have incited women’s rage. The problem can be summarized in a couplet: When wearing a kimono, walking was a no-no. In fact, if there wasn’t a Japanese equivalent of the saying “all dressed up and nowhere to go” back then, there should have been. Because the imperial court women of the time lived that dilemma every single day. Worse, in the Heian court being “all dressed up” meant more than just wearing a fancy outfit. It implied wearing a traditional kimono, which, according to Liza Dalby in her book Kimono: Fashioning Culture, at one point consisted of “as many as twenty layers” of silk gowns of varying heft and transparency depending on the season.” If these women did have somewhere to go, all those kimono layers made it almost impossible for them to get there. For as Dalby writes of these women, “Dressed like butterflies but having the mobility of caterpillars, they may well have crawled within the confines of the (palace) quarters as much as they walked.”

Even within the palace, all that people saw of these women were the parts of their garments that they were permitted to expose. For they presented a “faceless display” called uchide or idashiginu, “putting out one’s robes” from “behind blinds and curtains” that hid their faces. As if this self-effacing pose wasn’t humiliating enough, the women were told exactly how to arrange their many layers to strike it. This practice was like a very early version of Madonna’s voguing, except there was no way to let your body dance to the music or go with the flow.

When riding in a carriage, the women went from being mannequins to marionettes. The only part of them that could be seen as the carriage passed by was the kimono sleeve they draped outside the window on one side. This custom, Dalby explains, led to the making of unbalanced kimono gowns with “inordinately wide sleeves” on the side displayed out the window. These sleeves were so heavy that they “had to be supported by a hidden thread attached to a stick of bamboo skewered behind the seat.” So a powerful Japanese empress was in a way the original puppet ruler.

In Japan’s neighbor China, from the twelfth to the twentieth century, the mode of dress allowed women to walk but forced them to do so uncomfortably. I knew that the barbaric custom of binding girls’ feet came about because small-minded Chinese men had a thing for small feet. But then I read in Are Clothes Modern?, by Bernard Rudofsky’s that these Chinese women’s feet were squeezed into shoes with high heels, forcing them to take small, unsteady steps — a gait that also appealed to men.

Another impediment to women’s walking that Rudofsky cites originated in the Orient but stumbled into Europe via Venice by the seventeenth century: the chopine. This was a wooden platform covered with leather of various colors and attached to women’s shoes to add as much as twenty inches to a woman’s height. To walk the walk that men so admired from ground level, the unbalanced women needed an attendant or at times one on each side on each side to keep herself upright. I wonder if ambitious attendants could promote themselves by stating that if a gentleman took the bait, they would then perform double duty by acting as chaperones, too?

Lest contemporary women pity their Chinese sisters of unenlightened times and wonder how they stood for such foot abuse, in another of his books, The Unfashionable Human Body, Rudofsky indicts today’s fashionable high-heel shoes for causing bunions, callouses, corns, ingrown toenails, and hammer toes. And to give his reasoning in a rewording of an old show tune, fashion history repeated itself because a “doll” was only doing it for some guy turned on by her pained gait.

But Rudofsky wasn’t just a critic and historian of fashion. He was first and foremost an architect with an eye for design, and so, with his wife, Berta, created the foot-friendly Bernardo Sandals. The sandals were made with flat leather soles that followed the outlines of the foot and festive, rustic straps. (Bernardo Sandals are still available today, in the original design and others.)

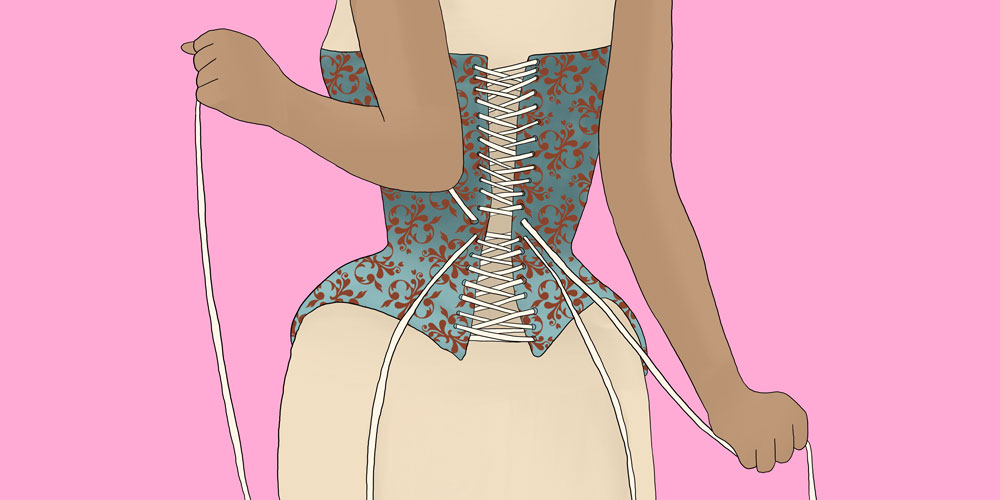

As though changing the way women naturally walk was not bad enough, Rudofsky joined a chorus of fashion commentators criticizing those throughout history who were bent on changing the very shape of women’s bodies, “much like automobile bodies or storefronts.” Karen Bowman, for one, details the slings and arrows women have suffered in Corsets and Codpieces: A History of Outrageous Fashion, from Roman Times to the Modern Era. She tells us the corset was introduced in Europe in the 16th century, and its design and details evolved over its decades of use. But its purpose was always to make the waist narrow by pulling on the corset’s strings, flatten the front of the bodice rigidly with stays and push up the breasts so they nearly popped out of a dress.

Popular for just a decade in the mid-19th century — fortunately, given all the accidents it caused — the crinoline put women in a “cage.” Yes, Bowman writes that was the name used for the bell-shaped, steel structure that women slipped on first to support as many as six petticoats and the dress worn over them. The bustle was a scaled-down version of the crinoline silhouette, created by flattening the front of the dress, pulling all the petticoats back, and draping them over a pad or cushion — the bustle itself — worn just below the waist.

If a tightly laced corset was ever advertised on TV, making use of Bowman’s text, the voiceover would sound like the ones we hear in today’s ads for some medications: “Wearing a corset may cause head-aches, giddiness, fainting, pain in the eyes, pain and ringing in the ears, nose bleeds, displacement of bones in the chest, shortness of breath, spitting of blood, consumption, derangement of the circulation, palpitation of the heart, water in the chest, loss of appetite, squeamishness, vomiting of blood, depraved digestion, flatulence, diarrhea, dropsy, melancholy, hysteria and a red nose.” Oh, the lucky ladies who got away with just giddiness!

Wide crinoline dresses billowed out so much in back that women wearing them were often unaware of how close they were to a fireplace. Punch magazine joked that since these dresses caught fire so frequently, petticoats should be fitted with tubes that contained water and a means of spraying it, creating a hybrid dress/fire engine.

In the workplace, wearing a bustle was a hassle. Corsets and Codpieces records that in 1888, the fastidious manager of a shirt factory in Huddersfield, England, banned the wearing of bustles by his employees. His edict was based on his observation of his young female employees and the resulting calculation: a girl arranges her bustle for one minute, five times a day, for a loss of five minutes. If you employ 12 girls to make shirts, that means the loss of a whole hour of production. Sounds like the production of bustles should have been banned.

Another incident from 1888 occurred while Charles Dickens was giving a speech at a church in San Francisco. He was interrupted by the sound of a “small explosion” in the audience, which turned out to come from the popping of one woman’s inflatable, rubber bustle. The embarrassed woman probably wished she could have vanished like the ghosts in Dickens’s A Christmas Carol.

In his Are Clothes Modern, originally the catalog for the 1944 exhibit of the same name at the Museum of Modern Art, Rudofsky was as critical of the era’s clothing as another architect, Frank Lloyd Wright, was of its houses with rooms like boxes inside of boxes isolating its inhabitants from the outside. Rudofsky mocks the silliness of the “fashionable mono-buttock,” a throwback to the “mono-bosom” from the turn of the century: “Modesty decrees today a uniform posterior bulge, achieved with the help of a barrel-like contraption, called, not altogether happily, a girdle.”

Today’s more comfortably dressed men, Rudolfsky notes, should feel sorry for their fathers and grandfathers when considering their attire for a ‘formal occasion”:

“The kind of clothes we seem to cherish most are, in good measure, designed to punish and damage our bodies. The gentleman who “does not feel like a proper man” without a stiff collar becomes, through the strangling effect of his neckwear, purified and redeemed. Not only providing him with personal discomfort, but the pressure on his thyroid cartilage also generates a feeling of moral well-being.”

Sometimes ill-fitting attire or footwear can be not only uncomfortable, but also dangerous. As in World War II, Rudofsky points out with ire:

“War correspondents told of the plight of British soldiers in the early stage of the Malayan campaign, who, deprived of motorized transportation, were unable to flee because their footwear had crippled them….It is a fair speculation to think of such a soldier who, surviving the years of captivity with his memory intact, comes back to wring the neck of the shoe designer. And should the court absolve him of guilt, his example will open a new and more human era.”

The more Are Clothes Modern? enumerated the discomforts of getting dressed, the more curious I became about what Rudofsky deigned to wear himself. I began searching for photographs of him, but found only two: one of him in a standard white lab coat and another in a traditional Japanese jacket, which made sense not only because he had lived in Japan and written a book titled The Kimono Mind, but also because it’s looser fitting than the Western suit jackets he had denounced. But when I searched the New Yorker archive to see if the magazine had covered his “Are Clothes Modern?” show, I hit pay dirt.

My search returns included a 1944 piece by Brendan Gill about his visit to the exhibit when Rudofsky and his wife were also there. The architect had a suit on, Gill writes, and then adds:

“…but by preference, and at home, he goes about naked, as does Mrs. Rudofsky. While in Italy, he and his wife hired a Swiss maid, who was at first deeply shocked to see her employers wandering naked around the house and yard. As the months went by, however, she began to strip, and by the end of the year she was waiting on table as bare as the day she was born and not giving it a second thought.”•