For hundreds of years, and through today, overseas shipping has been the primary method of global trade. During most of that time, the loading and unloading of cargo involved hundreds of workers manually hauling crates — that is, until containerization revolutionized the industry. Beginning in the 1960s, shipping companies adopted standardized containers, which could seamlessly be lifted from trucks onto ships with enormous cranes and unloaded the same way. Suddenly, the number of workers necessary for a dock’s efficient operation dropped exponentially.

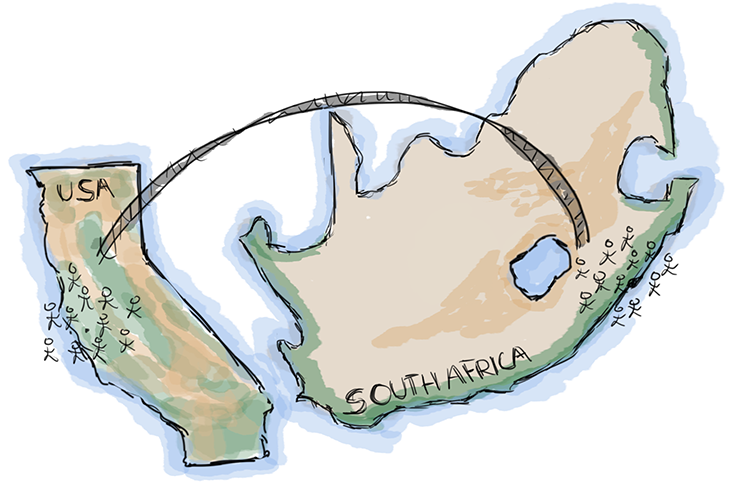

Historian Peter Cole’s recent book, Dockworker Power, tells the story of how two different groups of workers — the International Longshore and Warehouse Union’s Local 10 in the San Francisco Bay Area, and formally unorganized, but radically minded dockworkers in Durban, South Africa — dealt with the automation of their industry. Being formally organized and relatively powerful, ILWU’s Local 10 was able to negotiate what amounted to substantial retirement packages for its redundant members; being unorganized and clenched in the fist of apartheid, Durban dockworkers were not able to win such concessions.

These histories provide two paths for workers everywhere who are threatened by automation — the organized winning compromises, the unorganized swept aside — but the most interesting route is the road not taken. Even after Local 10’s supposedly successful negotiations, some union members questioned if further radical conflict, rather than compromise, would not have served them better by preserving their power, rather than selling it.

For a hint of what could have been, readers can turn to the other portion of Dockworker Power, in which Cole describes how both Local 10 and Durban dockworkers applied their collective power to social and political ends — most notably in the civil rights and anti-apartheid movements. If dockworkers could help change the faces of their countries in such transformative ways, how might they have been able to change their industries through further collective action? I recently spoke with Cole to find out. Our conversation below has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

Arvind Dilawar: How did you first become interested in dockworkers? And why did you decide to write a comparative history of dockworkers in the San Francisco Bay Area and Durban, South Africa, which seem worlds away from each other?

Peter Cole: While in graduate school pursuing my Ph.D. in U.S. history and searching for a dissertation topic, I wanted to find a labor union that was anti-racist and anti-xenophobic. That’s because I believe that the greatest power that we, ordinary people, have is achieved when we act collectively on the job. History demonstrates that organized labor — via strikes, unions, and other forms of collective action — has been and remains the greatest single force for equality and against poverty. However, as a budding historian, I also appreciated that employers had used “divide and conquer” tactics countless times to weaken workers. If American workers went on strike, employers brought in immigrants. If Irish immigrants struck, the bosses brought in African Americans. If Mexican Americans unionized, in came Italians. If men went on strike, women were recruited as scabs. And so on. As if I need to remind anyone reading this piece, why are ordinary Americans being made to hate immigrants from Honduras? Donald Trump, a notoriously hateful and stingy employer, clearly appreciates the effectiveness of this strategy.

So I wanted to research a multiracial, multiethnic union because that’s the best way to fight poverty and inequality. Guess what? Not many such unions existed in U.S. history, especially before the 1930s, and I was interested in the industrial era before and after the turn of the 20th century. It just so happened that perhaps the most racially integrated union in early 20th century America was of dockworkers in Philadelphia, then one of the largest ports in the nation. When the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW or “Wobblies”) lined them up, they were about ⅓ African American, ⅓ Irish and Irish American, and ⅓ East European immigrants. They dominated the waterfront for nearly a decade before a combination of employers, governments, a more conservative rival union, xenophobia, and white supremacy upended their power. Just so happened they were dockworkers. I later came to realize, however, that was no coincidence.

While finishing up that first book, I had the chance to teach at the University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania. That’s in East Africa, but I also visited South Africa. I traveled there for the same reason many others have: to see, first-hand, the place that experienced the long struggle against apartheid, which many consider the greatest social movement of the post-WWII world. I was captivated and wanted to incorporate South African history into my research, but also was mindful of my ignorance and did not wish to be seen as just another interloper from the Global North. So it seemed best to combine my existing knowledge of US history, build on my expertise on African American and labor history, and engage in comparative and trans-national research.

Through the course of my earlier research, I also had come to learn that the dockworkers of the San Francisco Bay Area belonged to a union that was among the most powerful and progressive in all of U.S. history. Before you know it, I’m writing a book comparing the histories of militant dockworkers in Durban and San Francisco.

AD: How were dockworkers in the Bay Area and Durban able to organize — either formally or informally — in such difficult conditions, where continued employment was in no way certain and unions were not legally protected? Were their tactics similar despite the different contexts?

PC: Dockworkers in these two ports — and countless others across the Seven Seas from Valparaiso to Istanbul to Singapore — have organized to improve their wages, conditions, lives, and world. Before the massive technological change that was containerization, which occurred in the 1960s and 1970s, gangs of men (historically this work was all-male) labored in tandem to load and unload cargo. No one could load a ship alone. Also, the inherently dangerous nature of the work created incredibly tight bonds among dockworkers. Moreover, there was little to no opportunity for dockworkers to move up the ranks into being a ship captain or shipping executive. There was a clear, bright line between bosses and workers, us versus them. Hence, the work process inculcated a collective identity.

Of course, dockworkers in Durban and San Francisco also were different for some obvious reasons and less obvious ones. In San Francisco, and across the United States, workers had the legal right to strike, unionize, and collectively bargain from 1934 onward. Durban dockers, who were all black Africans (mostly Zulus, some Pondos) were denied rights as workers due to massive racism that became codified after WWII as apartheid. When SF and other Pacific Coast dockworkers shut down the entire coast, in the summer of 1934’s “Big Strike,” they had tremendous solidarity but they also had legal rights along with the most pro-worker president in US history, FDR. He and Frances Perkins, secretary of labor and the first-ever woman in a presidential cabinet, pressed employers to accept the new normal. Additionally, even in the Bay Area, dockworkers engaged in repeated short, unannounced work stoppages, sometimes called “quick strikes,” to press shippers. Like dockers, seafarers, and other workers in transport have long known, they possess power because of that well-known saying, “The ship must sail on time,” as well as another familiar one, “Time is money.” Literally every minute, every hour, every day that cargo doesn’t move, some company is paying extra.

Interestingly, starting in the late 19th century, Durban dockers turned their lack of formal employment — their casual status, also referred to as precariousness — to their advantage. Before 1960, no docker was guaranteed a job, ever. Instead, each day he was obligated to show up on the waterfront hoping to be selected. In order to press their claims, generally for a raise, dockers repeatedly coordinated “stay-aways” in which none of them reported to be hired. Legally, such an action was not a strike because they had no steady employment. Such a clever tactic was, in everything but name, a strike yet avoided breaking the law that denied black workers such a right. While most such actions were about raises, there was always a political tinge, meaning any time that black people demonstrated power — by challenging the white power structure, which also can be named racial capitalism — it was a threat. That’s why the Durban police, city government, and the national government repeatedly cracked down so hard on Durban dockers via mass firings, police repression, and more. By the late 1950s, Durban dockers coordinated their work stoppages with nationwide “stay-aways” declared by the African National Congress and other allies in the anti-apartheid movement. That’s why the city and bosses reorganized the system to decasualize the waterfront in 1959.

AD: Dockworkers in the Bay Area and those in Durban played pivotal roles in the US labor movement and South African resistance to apartheid, respectively. What is it about dockworkers that puts them “in the center of the action,” so to speak?

PC: In the port of San Francisco in the 1930s, the workforce was 99 percent white, literally. However, many members of Local 10 — the SF branch of the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU) — were socialists, communists, and Wobblies, so were anti-racists in principle and, as their history demonstrates, practice. They instantly integrated their work gangs and insisted on equal treatment for black members. When a massive labor shortage, induced by WWII, launched another wave of the African American Great Migration, Local 10 opened its ranks to more than 1,000 black men; by contrast, shipbuilding unions denied black men and women membership or segregated them. After the war, Local 10 continued recruiting black members and, by the late 1960s, was majority black, with its first black president. Local 10 stood at the forefront of local and national civil rights activism in the 1950s and ’60s. They also lent their power and prestige to the organizing of California farmworkers, the Pan-Indian occupation of Alcatraz, the massive student strike at SF State, and more.

By the same token, black dockers’ contributions to the struggle against apartheid were mighty. Durban was the largest port in South Africa and the country’s economy very much depended on exports and imports through Durban. What happened on the Durban waterfront very much shaped the nation. In particular, they contributed, in the late 1960s and early ’70s, to the resurgence of the domestic anti-apartheid activism.

What is it about these dockworkers? Or the dockworkers and sailors in the Port of New York City who, in 1935, boarded a German ship to tear down the Nazi flag? Again, the nature of the work created cosmopolitan, internationally-minded people. Every day, dockworkers met folks from other parts of the world while loading and unloading cargo. They were introduced, accordingly, to new cultures, ideas, and people. Even though some might not have as much formal education, they were — and remain — more aware of and knowledgeable about the wide world than a great many other people.

AD: Much of Dockworker Power focuses on how the International Longshore and Warehouse Union’s Local 10 in the Bay Area and the formally unorganized, but radically minded dockworkers in Durban each dealt with automation. What lessons can be drawn from their experiences for the benefit of other workers threatened by automation?

PC: When I started researching my book, I had no intention of investigating technological change. However, as I dug deeper I realized that the ILWU literally was the first union in the world to negotiate the transition from traditional dockwork to containerized shipping — and this technological change was revolutionary. I don’t use that term lightly, but a seemingly simple metal box dramatically reorganized and expanded global production and trade in the past two generations, forever changing global capitalism. Few technologies have been more influential, yet few have examined how this technology impacted those in the transport industry. As I see it, today, there is no more pressing issue in the world’s workplaces than automation. Thus, a third of my book ended up exploring this incredibly important yet widely ignored topic.

To try to sum up such complicated matters: The ILWU negotiated with an employers’ organization over how containerization proceeded. Let me first underline that employers almost never ask their workers permission before introducing new technology, so keep that in mind. In short, ILWU International President Harry Bridges, a legendary left-wing radical and still a hero to most longshoremen, convinced his ornery, left-wing membership to accept this shift in exchange for a few major concessions. First, not a single worker in that generation was fired. Instead, the union got employers to contribute a lot of money to pay older longshoremen to retire — what Bridges called “shrinking from the top.” Second, workers’ wages significantly increased, what he called, a “share of the machine.” However, over time — and as everyone knew would happen — the number of dockworkers shrunk dramatically. Now it takes maybe 10 percent as many workers to move 10 times as much cargo as before containerization. By contrast, the Durban dockers had no union nor sufficient power to force employers and the state to talk about, let alone negotiate over, this shift. Within three years, half the Durban dockworkers were fired and those remaining didn’t receive a single penny more in wages.

What lessons might other workers learn? For one, unions matter — greatly. The wages, conditions, benefits, protections, pretty much every measure are better with unions. Also, only if workers already have power can they get ahead of any potential technological shifts. But I don’t mean to suggest that is sufficient. Even the ILWU, with its energized rank-and-file, impressive organization, and strong politics, bargained from a position of relative weakness. Workers also need allies in the community and government.

AD: One of the most interesting aspects of the dockworkers’ struggles against automation is “the road not taken,” or the opinion of some ILWU members that it would have been better to fight to preserve their power, rather than selling it via what amounts to very generous retirement packages. Do you think that fighting was a viable option?

PC: To me, the road not taken was the push for the six- or even four-hour day. In the United States, the fight for the eight-hour day began in the mid- 1800s and didn’t succeed, nationwide for wage workers, until the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. But why did we stop with the eight-hour day? That’s not a magic number. Given the massive increase in population and huge productivity gains made in every industry, due to new technologies, I cannot think of a good reason why we continue to toil for eight or more hours every workday. Basically, most of the gains have gone to employers and owners. I presume nearly all of us would embrace a four-hour day with no decrease in earnings.

To my knowledge, there was not a serious conversation in the ILWU, in the late 1950s and early ’60s, over this matter. Bridges, the supposed communist (definitely a leftist), negotiated a really great financial package for his members, but that doesn’t seem very socialist. By 1970 or so, there was a whole lot of anger, however, along the waterfronts of the Bay Area and other West Coast ports. When Bridges proposed a third automation contract, more than 96 percent of the members rejected his recommendation and went on strike instead. Alas, Bridges utterly failed in leading that strike and, despite it lasting longer than any other in US maritime history, no major gains were won.

Could the ILWU have thrown down the gauntlet in 1960? Maybe, but it would have been tough and, no doubt, Bridges and others were thinking about that. The Second Red Scare, also known as McCarthyism, had weakened the ILWU, the entire labor movement, and liberals more generally. The ILWU, in particular, was quite isolated because the mainstream AFL and CIO unions had purged their leftists and merged, moving further rightward; Bridges feared that the more conservative East Coast longshore union might try to move back West or even the Teamsters might seek to pick off some locals. Plus, the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 had drastically weakened unions. The union’s first automation contract was signed before the explosion of social movements (first civil rights, then anti-war, and much more) in the 1960s, and once the US escalated its war in Southeast Asia, the union could have been crushed using the excuse of military emergency.

I do think that the union could have fought harder and also refused some of the provisions of their agreements. I talk about these matters in my book, but the short version is that the ILWU missed an opportunity, in my opinion, to press not simply for more money, but also another major supposed benefit of technology. Tech used to be praised as “labor-saving devices.” We don’t hear that term much more because employers dominate the narrative. That has to change, and it’s not going to come from above but, rather, below. •