I remember a lake rimmed with lily pads; a meadow filled with sun. The uphill stretch of trail where I stepped round a bend and came eyeball to eyeball with a mountain goat. Now, the goat may have been a bighorn sheep. It wasn’t the curve of the horns, so much, or the softness of the hair, that I remember, but the animal’s expression. It looked bemused.

This was many years ago and my husband and I were in Glacier National Park, Montana. We’d driven south from Alberta, where we lived at the time — on holiday, with no fixed plans but to be in the mountains.

At the eastern edge of Glacier, there’s a little place called St. Mary, at the start of a famous highway across the park, twisty and narrow. We checked into a cabin near a visitors’ center where you could get dinner, cafeteria-style, surrounded by vastness, and unpacked our car.

Before we’d left home, a friend had dropped by to lend me a new book she’d just finished: The Stone Diaries, by Carol Shields. I’d never heard of the book, or the author, but I’d tucked it in with our trip gear, among the backpacks and bear scares and boots. There was no TV in the cabin, of course, this being the wilderness, a setting we’d think of today as conducive to digital detox. I remember the sense of utter relaxation, settling in, at the end of the day, with a glass of wine, cracking open a book recommended by my friend. The story of Daisy Goodwill, a fictional woman, born on the Canadian prairie at the turn of the twentieth century, begins in a hot Manitoba kitchen with Mercy Stone Goodwill, Daisy’s mother, making a pudding for her husband, a worker in the limestone quarries — a pudding of stale bread, raspberries, and cream. Eating, for Mercy, was as close to heaven as it gets. And almost as heavenly as eating was the making — how she gloried in it! Every last body on this earth has a particular notion of paradise, and this was hers, standing in the murderously hot back kitchen of her own house, concocting and contriving, leaning forward and squinting at the fine print of the cookery book, a clean wooden spoon in hand.

We must have had a hiking guidebook, recommending certain trails, and in the morning, we set off through a fir and pine forest. Sunlight dappled the forest floor, which was lush with lady’s slipper and mosses. After a steep climb, the trail emerged above the trees onto a sunny ridge where we stopped for a while, on top of the world. We crossed rocky ledges and little streams before the trail dipped down to a lake, iceberg cold and ringed by cliffs. From the middle of the lake, a moose observed us, or it may have been an elk.

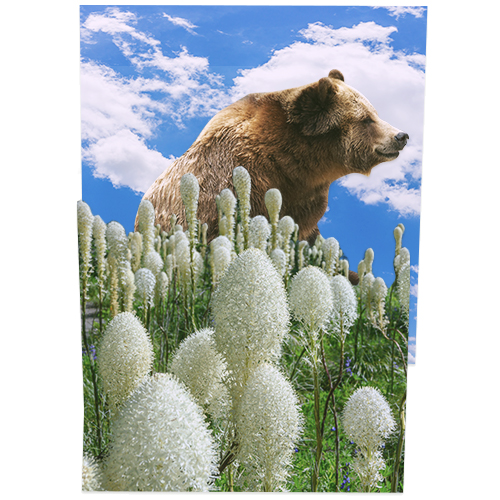

When I think of Glacier National Park today, I think of beargrass — creamy flowers on tall stems, plume-like, fluffy. Beargrass — perhaps because it’s lovely and special, unique to northwestern North America, blooming in parts of Glacier when conditions are ideal. Every seven years? Every 10? Depends on whom you ask. Years earlier, on a day hike, deep in bear country in Canada’s Waterton National Park, over the border from Glacier, we’d crossed a meadow of beargrass, roaming in flowers up to our shoulders. I made a point of singing and shouting, so as not to surprise the bear I fully expected to encounter. This was before I learned that bears don’t eat beargrass — although surely, they wander through it. What’s more, beargrass is not a grass, but a type of mountain lily. Beargrass is also known, more factually, as elk grass, and less whimsically, as turkey beard. And yet, I like to imagine a grizzly bear bedding down for the winter, layering its den, for warmth and softness, with beargrass, pawing the leaves into place, with perhaps a few flowers.

We camped out in the cabin for a day or two more, falling into a routine of walking all day and in the evening, after dinner reading. Daisy Goodwill grew up, married, and moved to Indiana. Maybe now is the time to tell you that Daisy Goodwill has a little trouble with getting things straight; with the truth, that is. She had a golden childhood, as she’ll be happy to tell you. Her loving “Aunt” Clarentine, her adorable “Uncle” Barker. Warmth, security. Picnics along the river. A garden full of flowers.

Daisy, as a narrator, isn’t always reliable when it comes to the details of her life. Still, hers is the only account there is, written on air, written with imagination’s invisible ink.

What I remember most of Daisy’s story is the way it was told, the various and surprising perspectives. Daisy’s voice on one page, an omniscient narrator on the next. Or a newspaper clipping, or a luncheon menu, or a recipe for pudding.

They say Glacier Park has two seasons: winter and the fourth of July. In the mountains, it can snow any time. And yet, that week, that year: no snow, no rain, the trails so warm and cloudless I wanted to wander the mountains forever. There were no mosquitoes either, or for that matter, many people. We drove the Going-To-The-Sun Road across the park, from east to west, over the Continental Divide, our car hugging a wall of rock, precipitous drops on the other side. Today, with three million people visiting Glacier every summer, you can’t drive the famous highway on a whim. You must make a reservation. On a popular trail in the park, there might be hundreds of other hikers. But that fall, we had 1,500 gorgeous square miles of wilderness practically to ourselves.

A few months ago, while paying a utility bill online, I was asked to name my favorite author to verify my identity. As I typed in “Carol Shields,” my secret answer to the favorite author question for as long as I can remember, it occurred to me that I haven’t read a book by Carol Shields in nearly 30 years. And yet, the answer was unequivocal, like my birthplace or my eldest sibling’s middle name. It made me wonder what other books I’d read back then that I loved. I couldn’t think of a single one. It made me wonder how one book, one author, has stayed with me so long, although my true answer to the favorite question probably changes every year. I wandered over to my bookcase, and then remembered, The Stone Diaries wasn’t even mine.

A few days later, I bought the book, the Kindle version. The cover looked different than what I’d imagined, the e-book in no way reminiscent of the little hardcover book I remembered, on a nightstand in a cabin, or in a patch of sunlight on the back shelf of a car. But the contents felt familiar — the chapter headings: birth, childhood, marriage, love, motherhood, and so on. The family tree, the photos of Daisy’s ancestors and friends. (Some of the photos, I later learned, were pictures of Carol Shields’ children.) A novel, in the guise of autobiography.

In a forward to the Kindle version, dated 2001, Carol Shields talks about borrowing the framework for her novel from the design of a 19th-century biography. And how she knew, early on, that she was not writing a family saga but a book about whether we can know the story of our own lives. How much of our existence is actually recorded, how much invented, how much imagined, how much revised or erased? Carol Shields was writing about autobiography, and I suppose, about remembering beargrass and lily pads and switchbacks while forgetting something else.

In a radio interview in 1994, the year The Stone Diaries won the Pulitzer, Carol Shields, who died in 2003, talked about the story we carry in our heads, the story we think of as our life story, and how while reading over her manuscript, she’d realized that Daisy, in telling her story, had skipped over certain life experiences — childbirth, sexual initiation, education. But that’s how life stories are. It’s as though you end your life with a boxful of snapshots. They may not be the best ones, but there’re the ones you have. All the other pictures are in an album somewhere.

When I bought the Kindle book, I’d planned to re-read the story of Daisy Goodwill, the story of how her mother had died giving birth to Daisy and how her father had built a stone monument in memory of his wife. Daisy’s marriages. Her children. I’d intended to refresh my memory about Daisy’s work as a newspaper columnist, and how she wound up, as the century closed, in a nursing home in Florida. But somehow, I never did.•

Source images courtesy of George Theodore/Danita Delimont, Lumos sp, amarinchenko106, Archivist, kellyvandellen, sparkia and ParinPix via stock.adobe.com.