“I suspect that cooking with love is an inversion of a different principle: cooking to be loved,” Bill Buford says in Heat. Perhaps that’s why eating a restricted diet feels so lonely: cooks — whether they are homespun or professional chefs — are deeply annoyed by being confined or regulated. If you are on the receiving end of this annoyance, it feels personal, especially if your finicky-ness is a result of necessity rather than preference. But for the person preparing the food, even a simple request can create a major upheaval, undermining both flavor and technique. Food designed for specialized diets tends to expel puffs of uncertainty and sometimes disdain. (If you don’t believe me, just go to your favorite pizza joint and order a gluten-free crust. If they have one, it will almost certainly be served either nearly raw or burnt, and although it may have the same sauce topping and cheese as your usual order, it will exude none of the decadent coziness of your typical slice.)

Studies show that comfort food is comforting because of association: It soothes by reminding us of one who once calmed us, but this only works for the emotionally healthy, those with a “secure attachment style,” people who have generally positive associations with and trust in relationships. For those raised in a supportive environment, eating the foods of their childhood provides a link to memories of emotional support, making them feel less alone. But for those of us whose early relationships were troubled, familiar food does not alleviate isolation. We cannot imagine away loneliness. When what’s familiar is painful, seeking comfort requires us to do the uncomfortable work of trying something new. Paradoxically, to be soothed, we must seek out the unfamiliar, leaving what is deceptively called our comfort zone.

This is especially true for those with digestive disorders that mandate restricted diets, but their plight draws little empathy from outsiders. This may in part because so many of us — 74 percent, according to a recent poll — live with digestive discomfort; it may also have to do with the growing number of Americans who follow limited diets by choice. When my sister first developed irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), my parents and I treated her as if she had joined a distasteful cult. Why did she insist on avoiding all the foods we loved? If she had to eat bland meals like white rice and chicken, why couldn’t she just do it in silence while the rest of us gorged on ham, cheesy potatoes, and pie? What was wrong with her anyway?

When I too was diagnosed with a condition that required management through major dietary changes, I experienced first-hand the difficulty of refusing favorite foods. Now I’m abashed at my former indifference. Was it a lack of imagination that made me so uncaring, or was it something more cynical: a disbelief in the severity of her symptoms? When we can’t see what is wrong, there is more room for denial, for us to assume that suffering is a choice.

When I could no longer eat wheat, my mother stopped sending care packages. She used to mail iced hearts and chocolate logs in sturdy thrift-store tins decorated with snowflakes or flowers. Their discontinuation made our connection feel tenuous. They also made me see the packages differently: not as a selfless maternal expression of love but a creation gifted in hopes of gaining acceptance and appreciation.

The end of the care packages felt like a rejection, but I hadn’t always received them happily. When she sent a batch of oatmeal chocolate chip cookies to console me when my high school best friend died, I was angry and offended. It felt dismissive, as if she thought that loss was something that could be cured with a good cry and sticky fingers. Still, I ate the cookies, hoping they would provide some measure of comfort.

•

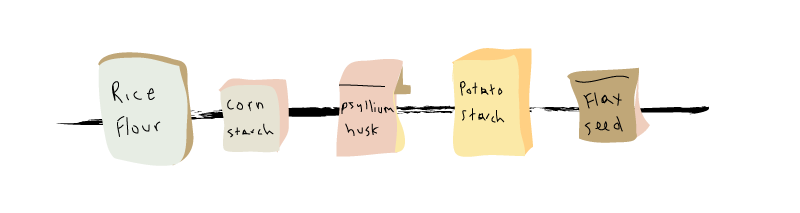

When I first stopped eating wheat, I was optimistic. I’d seen gluten-free offerings at my local Kroger. They were expensive, but I was used to paying more for quality, already being the sort of shopper who selected organic produce and grass-fed beef. I purchased a tiny six-dollar box of cookies and an eight-dollar loaf of bread with hopeful anticipation. The cookies were somehow both gluey and crumbly. The bread tasted like oily Styrofoam. After eating half a slice, I cried and started reading about gluten-free baking. Soon my freezer was packed with teff flour, potato starch, and psyllium husk. I avoided eating out and eating with others. Away from home, I always craved what I couldn’t have: pizza, sandwiches, pillowy naan.

I eventually accepted and stopped testing my limits. I ate well at home, where I could easily alter and substitute to fit my stomach’s finicky preferences. But eating with others was never the same. Restaurants called for restraint, intuition, and assertiveness. I snuck my own gluten-free snacks into coffee shops. I brought my own snacks to parties. But still, I felt loss, an emotional craving. It wasn’t the food I missed so much as the connection. I missed being easy-going. I missed ordering pizza with friends or splitting a sandwich. I missed swooning over menus. I could no longer eat socially, adaptably, willing to try anything. My new way of eating made me high-maintenance. I was forever asking after ingredients, requesting specialty menus.

•

A compromised sense of identity is a common side-effect of dietary changes. In cultures with spicy cuisines, the elderly often experience a sense of loss as they lose the ability to tolerate heat. When Vietnamese chef Andrew Pham came down with dysentery upon returning to the country of his birth, he experienced a sense of rejection, as if his native cuisine was telling him he no longer belonged. In her essay “If You Are What You Eat, Then What Am I?” Geeta Kothari worries that her aversion to lentils and hot spices “signals something deeper . . . that somehow [she is] not [her] parents’ daughter, not Indian . . . and not American either.”

The assumption of agency, of control, over our suffering creates space for indifference. We care easily and generously for those we perceive as helpless and dependent: pets, infants. But for those with a degree of autonomy, we ascribe misery to poor choice. We say take care of yourself as an incantation against having to care for each other, a spell that provides an umbrella of justified indifference. We claim to cook with love, but when that love requires added effort or different ingredients, we stop offering. At family gatherings, my sister and I make our own food. At least she has company now.

We say you are what you eat because food is so intimate. The nutrients we consume are part of us. Our organs are made from nutrients that come into our bodies through our food. A trial last year showed significant improvement in depression symptoms for participants who adopted a healthier diet. Rosalyn Collings Eves calls recipes “a narrative framework” on which personal and communal memories are “constructed and infused with meaning.”

•

No longer able to participate in many aspects of food culture, I am sometimes able to observe it from a critical distance. Watching my boyfriend eat pancakes, I wonder: Does this familiar food really comfort him? Does eating heavy, starchy things make people feel better, or is its balm an illusion like smokers sharing cigarettes — more a matter of shared misery and habit than soothing? Do we eat comfort food because it eases our pain, or are we just numbing our loneliness?

The answer is complicated. Our most vivid memories often involve food: taste, smell, and rituals of preparation. For me, the smell of fried chicken evokes funerals, and the taste of my mother’s cinnamon rolls calls up a bundle of Christmas morning memories. But food doesn’t just trigger memory; it also enhances it. A study of children’s memories conducted in 2002 revealed that negative food memories like “being forced to clear one’s plate” were often strikingly lucid, even when a child could recall little else in specific detail. Perhaps this vividness is because eating involves a convergence of so many senses, or perhaps it’s because eating is so associative. We eat particular foods for specific holidays; our food choices are also tied to seasons, time of day, and who we are eating with. Consider the difference between a meal you’d eat at your parents’ house and one you’d eat with your friends.

We tend to think of comfort food as rich, delicious, and starchy, but the foods we reach for in stress aren’t necessarily decadent, just familiar. Comfort food isn’t always the most delicious. It is the food we know. Its appeal relies on nostalgia, and for that reason, eating comfort food — much like running into a former lover or returning to your hometown for the holidays — is often disappointing. It is easier to stick with what is well-known. We tend to surround ourselves with familiar people who share our preferences, opinions, ideas. But this easiness is often not quite what we’d hoped for, not quite as good as we imagined.

There are times I appreciate my limitations. When a coworker brings in doughnuts or is selling Girl Scout Cookies, I no longer feel obligated to participate. Eating sweets or baked goods now requires planning and intention. It makes them special again.

Scooping up the last melting mouthful hot fudge sundae, one tends to feel not a deep satisfaction but a lingering desire and regret. It is the same feeling that accompanies immaculate college campuses, gated communities, and the sprawling lawns of suburbia: a sense that things built from familiarity and nostalgia are syrupy and bland.

There are three times as many Americans with no close friends as there were in 1985. We also consume 23 percent more calories than we did in 1970. Without meaningful emotional connection in our present, we eat to connect to the intimacies of our pasts, reaching for fragments of comfort long ago. These meager morsels of love cannot cure loneliness. Memories fade, calories are consumed. True comfort is not about richness or sweetness or familiarity, but rather it is that which we receive with attention and care.

Considering the role of comfort feels especially essential in a time when our president is known almost as well for his love of ketchup and well-done red meat as for his aversion to dissent, difference, and diversity. The comfort of Big Macs and Diet Cokes is their constancy, a quality that is only possible when working with machines and processed foodstuffs. Trump preaches security through isolation, grasping at what is familiar. He tells us that by doing so we can stay safe.

It is a lie, but it’s a comforting one. •

All images created by Emily Anderson.