As you walk uphill from Bogotá’s iconic Colpatria Tower and through the Parque de la Independencia, you have only a few blocks before you meet the Cerros Orientales . . . the Eastern Hills. There the Adean city’s center abruptly ends in the shadow of Monserrate Mountain, a pilgrimage site since pre-Hispanic times. This plateau is where the Spanish had once hoped to find the mythical, gold-laden chiefdom of El Dorado. Sandwiched between these two landmarks is the city’s trendy La Macarena district, where, on street 26b, you’ll find an unimposing residential building painted mostly in black. It’d sat empty for years, and was slated for demolition. Now, however, it is Galeria Fenix, home to the Lavamoatumbá art collective founded by Chucho Bedoya.

Chucho Bedoya is a Colombian artist whose work is varied. He is a graffiti artist, painter, muralist, sculptor, and ceramic artist. Recent exhibitions of his ceramic work feature two themes: internet memes and criticism of Uribismo, the populist right-wing movement centered on ex-president Álvaro Uribe. Galeria Fenix, the third iteration of Lavamoatumbá’s efforts to convert abandoned urban spaces into cultural venues, follows the theme of the Phoenix “as a pretext to talk about everything related to life and death, rebirth, resignification or reaffirmation.” Between the ancient peaks and the bank skyscrapers, in the liminal spaces between urban/natural, new/old, rich/poor, life/death. A good theme for a nation in a liminal space of its own.

Politics, violence, and drugs have been inseparable for decades in Colombia. Yet the problems have deeper roots. Inequality centers on land ownership and stems from colonial times, as does systemic exclusion of Indigenous and Afro-Colombians. In the 1960s, many peasants formed leftist guerilla groups aimed at armed revolt, the most prominent of these being FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia). Five decades of violent conflict ensued, leaving hundreds of thousands dead and millions displaced. The situation was exacerbated by the rise in right-wing paramilitary groups and, with the end of the Cold War, the explosive growth in the drug trade, with all parties in the conflict partaking in it.

Enter the presidency of Álvaro Uribe in 2002, a large landowner with extensive connections to right-wing paramilitary groups. Securing $2.8 billion in support from the US, Harvard graduate Uribe and his Defense Minister Juan Manuel Santos would be implicated in the “false positives” scandal, wherein at least 6,402 civilians were abducted under false pretenses, murdered, and dressed as enemy combatants. Through such measures Uribe brought FARC and the country’s political left to their knees, before Santos himself would take over the presidency in 2010. Santos secured a peace agreement with the guerillas which promised large-scale land reform and investments from the state in neglected communities. In an act of high theatrical drama, Uribe and Santos then staged a political separation, with Uribe founding a new party and endorsing another candidate while Santos and his peace deal served as the foil. Finally, in 2018, Uribe’s “Democratic Center” party would succeed in bringing Iván Duque to the presidency.

By simultaneously reneging on government promises, defunding institutions responsible for fulfilling the peace terms, and continuing the ridiculously false Uribe/Santos melodrama, Duque has carried Uribe’s legacy forward. Widespread national protests have since followed, accompanied by brutal police crackdowns denied by officials but widely circulated in online videos. Just as a Special Peace Court has released testimony revealing “circumstantial evidence of U.S. government involvement” in the violent suppression of political opponents, the US has removed FARC from its terrorist list. The Colombian people, however, will not go so gentle into that good, Uribist night. At least not if they follow Bedoya’s example.

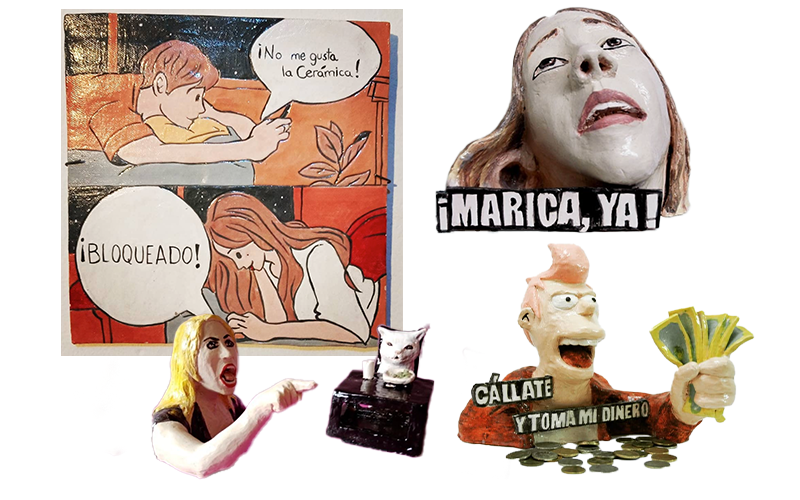

Bedoya’s current exhibit is called “Chucherías”, or “Snacks” . . . with a pun on his name, Chucho. There is something in the name which speaks to the graffiti artist’s desire to put his tag on the architecture enclosing him, but also something of the rapid consumability and ephemerality of its online source materials. They include symbols from the online landscape: assassinated comedian/journalist Jaime Garzón, Uribists captured on video threatening to fill protesters with “lead”… images which the government hasn’t been able to stop from circulating online. But while other dissidents have tried to imprint such images in the urban landscape in the form of street art, Bedoya’s ceramic creations do something distinct. The voice of dissidence is not relegated to either digital or urban mediums . . . it is made into a physical thing, an art commodity. This is rarer and rarer these days in Colombia, where more artists want to partake in the relative peace and prosperity of post-FARC days and avoid the political themes that could cause them personal harm.

Yet Bedoya, still a street artist at heart, isn’t just seeking to leave his mark on peripheral places. His work isn’t quite Monumento a la Resistencia, the statue constructed en masse by protesters this year in an occupied zone in Cali. All the better that it isn’t, for the anonymity and collectivity of such art is part of its function. Bedoya operates differently . . . within a space wherein property owners, local governments, and other institutions allow him to work toward a perceived mutual benefit for all parties. That’s an effort that any other artist might prefer to forgo for multiple reasons. Bedoya’s purpose, however, is communitarian. He says he is motivated by “pedagogy, giving people the critical tools to create critical works”. With that motivation, he also gives himself the tools to produce his own works which can “identify events, phrases, cases, objects, and characters that can hinder the search for social justice, and create a reflection and make them part of that imaginary that we have to keep in mind and not forget.”

Regarding his particular medium and subject, he says that “to speak of politics from the point of view of ceramics is to leave a reportable situation in an eternal material . . . rescue historical events . . . ” Eternal earth fashioned into the flickerings of current affairs. Seen in another way, Bedoya is taking a piece of Colombian soil in order to fashion from it the rapidly passing events working themselves through the Colombian soul, often uncontrollably and with little time for reflection.

My interest in making internet memes in an ancient language such as ceramics lies in being able to capture in an ancestral material things that do not last long in time, which are almost instantaneous, like a drop of water falling or a sneeze. From understanding this form of expression, the need also arose to communicate a political message, not to let it be forgotten but also to leave it stopped in time.

I ponder for a moment the notorious fragility of ceramics. Memes and graffiti leave little room to argue against Bedoya’s point here, though. Street art may earn the ire of neighbors or be painted over tomorrow. “However,” argues Bedoya, “political street art is not limited to a network or access, it is made for everyone, it must be much more democratic than the internet . . . especially in a country where not everyone has internet access.” Here, again, I question Bedoya. Much debated recently, internet access in the developing world has been alternatively credited with both fueling popular movements and stifling them. Akin, perhaps, to Coca-Cola being more accessible than potable water in some places, social media giants have made their services cheaper than standard internet access, to the point to which such services have practically become indispensable utilities in local economies.

There is a very real possibility that the internet language of memes will surpass any other form of political language in Colombia before long, if it hasn’t already. It feels like it makes sense in contexts where little else does. And the internet, as much as the streets ever did, represents a cultural commons. As an American, in particular, I must pause to reflect with curiosity on a political environment in which the internet isn’t necessarily assumed to be the crux of political discourse. With all these questions, it seems that Bedoya has hit some themes that may very well go beyond his present subjects.

“Social justice and inequality is something that will persist beyond Uribism,” Bedoya reminds us. Then, echoing the Sisyphean quest for El Dorado, on which this capital and all its turmoil was founded, he adds: “Utopia is like the horizon, the more you walk to reach it, the more it will move away.” Nevertheless, “Colombia suffers from a very particular political phenomenon, in which the ultra-right, the military, corruption, and everything that can be permeated by drug trafficking are governed under the same flow. Thus, the last thing that matters (to those people) is to fight to close the gap that affects the most vulnerable.” Too many discussions on public art here wax poetically about art and “community healing”, pathologizing criticisms of the new regime. Yet despite its long, violent history, nothing in Colombia will be healed without change. Bedoya knows this. And he knows that the stakes are high . . . the longer Uribism sticks around with its practices unchecked, the more likely further, worse practices are to surface later. •

Images found on artist, Chucho Bedoya‘s, Instagram.