The first and second part of this story can be found here: “Something about Sofia” and “Bleak Backwaters”

The City of the Tsars sits atop three hills rising from the meandering Yantra River: Tzarevetz, Sveta Gora, and Trapezitza. This self-proclaimed Third Rome and inland Constantinople was once the epicentre of the Second Bulgarian Empire; home to Emperors and Kings, Prophets and Patriarchs. Now, Veliko Tarnovo is a tourist attraction — the city walls have been rebuilt, along with ornate renaissance-era homes. Meanwhile, the charming old city, with its Armenian, Jewish, and Catholic quarters, is hemmed in by a sea of grey modernism.

In Tarnovo, Bulgarian statehood was resurrected after two centuries of Byzantine oppression. Brothers Asen and Theodor-Petar made the city their capital in 1185 AD. Tarnovo became the heart of a rapidly expanding Bulgarian empire, launching campaigns against the Epirusians, the Crusaders, and the Latins. Asen’s nephew Ivan captured the Latin ruler Baldwin I and returned to Tarnovo laden with treasure. Baldwin spent his final days imprisoned in Tarnovo’s tower. The now city reflects irreducibly complex anthropology, shaped by successive waves of subjugation, occupation, and liberation. Modern Bulgaria feels transient, like just another crashing wave.

Our hotel, the Arbanassi Palace was, until 1991, the BCP residence. It was the epitome of communist bad taste and the scale was mindbending. The oak lined corridors were practically intergalactic, and all shades of copious marble clashed beneath kitsch chandeliers.

“The Communists made everything big,” Nils explained.

Two decades of neglect had left this once respectable establishment looking more than a little run-down. Back in our suite, lights flickered and water trickled from the shower, and the room service, quite literally, failed to deliver. The next morning the vast breakfast hall was deserted, untouched cold cuts and cheeses whimpered pathetically from the corner. Gigi went to investigate. A whimsical attendant appeared bearing more cheese and meats

“But still no coffee!” Gigi exclaimed.

In Bulgaria, breakfast is a serious affair. There is no calorie-restricted nonsense; they consume the recommended daily intake before 8 am. And banitza is the chief culprit.

“Who ate all the banitsa!” They cry from the kitchen. But, as their saying goes, “the guilty one is he who let me eat it!”

Later, we walked the city walls and climbed the old fortress to survey Bulgaria’s rebel heart. I imagined the three-month Ottoman siege five centuries earlier. The walls of the medieval fortress — rebuilt in the 20th century — now rise above the city, crowned by the patriarchal church.

“The 1876 April Uprising started here,” Toshko explained, “It failed. But it marked the beginning of the end of Ottoman occupation.”

Further along, on a plinth perched above the Yantra, stands The Monument of Asenevci, a vertical double-edged stone sword flanked by chariots and riders. It simultaneously commemorates The Asen brothers, who led a bloody rebellion against their Byzantine overlords in 1186, and the Russo-Turkish War of Independence.

With the midday sun directly overhead we retreated to a tavern for lunch. Our waitress returned in no time, laden with stuffed peppers, fried aubergines, and the main event; a mountain of grilled meat decoratively configured around a pot of Lutenitza — the ketchup of Bulgaria. By mid-afternoon, we still hadn’t left the quaint tavern. Gigi was checking her phone and Nils was half asleep when a tray of thick coffee and blocks of Lacoumbe arrived. A variation of Turkish delight, Lacoumbe is flavored with rose oil and topped with moist walnuts — a delicacy Bulgarians will insist they invented and the Turks stole.

Gurko Street, named after the Russian General who liberated the city, runs through the old town of Tarnovo. At one end, the Forty Martyrs church houses the relics Tzar Ivan Asen II, amid the tomb of Tzar Kaloyan, the third ruler of the Second Bulgarian Empire. The medieval houses perch on the hillside, overlooking the Yantra. At the other end, four bronze horsemen stand guard. Off Gurko Street, Samovodskata Street is a timeless avenue of overhanging timber-framed buildings, where Blacksmiths, woodworkers, potters, metalsmiths, and icon painters still ply their trades today. Back at the Arbanassi Palace that evening we drank Kamniza, the mass-produced Bulgarian lager, on our rickety balcony, swaying precariously over the raging Yantra, some 50 meters (1/3 of a mile) below.

“Under the Asen dynasty Bulgaria experienced a second Golden age. Monasteries arose on the Sveta Gora hill, an academy was founded and palaces to rival those of ancient Rome.” Toshko was in fine fettle, adding his own wisdom to the information we had absorbed over the past days. “But fortunes of Tarnovo rose and fell on the unity and division of the Bulgarian state. The Asen dynasty was already decimated by infighting when the Ottomans arrived. Sultan Bayazid I besieged Tarnovo and Tzar Ivan fled. The patriarch managed to defend the city for three months before it was overrun. The walls were razed, monasteries looted, nobility slaughtered, and churches were converted into mosques.” Toshko trailed off to silence.

With the rise and fall of empire on our mind we bid Tarnavo farewell.

•

Mile after mile, Nils navigated the potholed roads while Gigi played on her phone, and Maria and I slept in the back — knocked out cold by the lethal AC. But when I awoke Nils was staring me down in the rearview mirror, looking right through me. There was no hiding on this trip. Nils and Gigi were very protective of Maria, and this was their chance to find out about the Englishman dating their daughter. When Bulgaria came in from the cold business opportunities abounded. His once athletic frame had been lost to decades of the hearty Balkans diet. Nils was a larger-than-life character — a self-made fixer turned silver-tongued diplomat.

“He started a logistics company. He had his own fleet of trucks.” Maria had explained.

Later, Nils explained. “I came over after the wall fell. They needed white goods, so I loaded up a truck and drove south. The business started from there and just kept growing. In 2004, I had over 100 staff. Those were the good times.”

“Then the recession hit us hard. Everything ground to a halt, our customers defaulted and eventually, like dominos, we did too.” Nils spoke in a detached tone, but from what Maria told me it had left him a broken man. A long silence followed.

“It’s the way of life here.” Nils concluded, “You don’t think with 10% corporation tax no one’s tempted to invest? The West just sees opportunity, natural resources, and cheap overheads. But they don’t understand the Bulgarian mind. They always end up getting stung.”

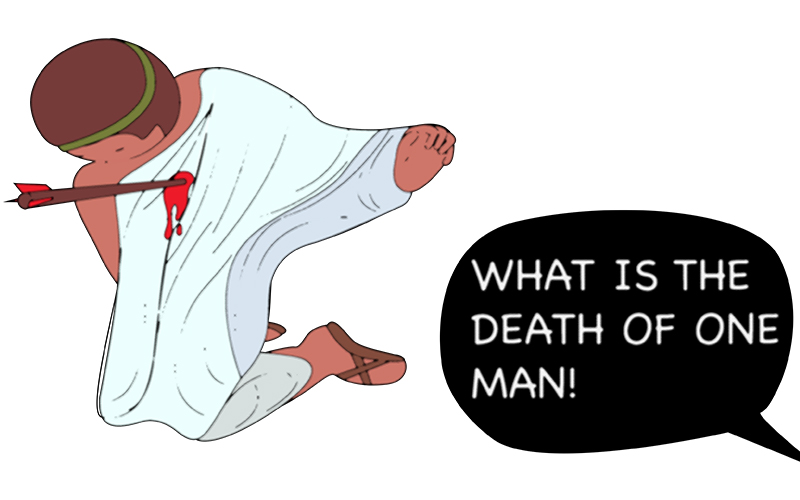

The road to the Black Sea followed the Beli Lom River, to the city of Razgrad. What little of note there is to see here is located around the Ibrahim pasha mosque in the Red Square, lined with Renaissance-era taverns. There was, however, plenty of museums; shrines to an array of semi-significant artists and statesmen. The real story of Razagrad is what lies beneath; Abritus — a 1st century Roman camp, and later center of Moesia Inferior — once guarded the empire’s northern frontier. Under King Cniva, the Goths crossed the Danube to raid Moesia and Thrace but, while besieging Nicopolis, they were surprised by Emperor Decius ‘the pope-slayer’, and Etruscus, his son. The Goths fled but mercilessly counter-attacked near modern-day Stara Zagora. Early on in the battle, Etruscus was killed by an arrow, to which Decius cried, “What is the death of one man!” Later, Decius met a grizzly end, entangled in a swamp.

•

To the North, an ellipsis-shaped Danube island once housed the notorious Belene labor camp, designed to re-educate opponents of the regime. Denied trials, agitators and dissenters, such as Toshko, were left to rot for several years.

“They slept with our bread under our armpits, to keep it from the rats.” Gigi recited some of her labor camp trivia, since Toshko never talked about it.

Communist agricultural projects desolated the land and their artificial floods ruined the harvests.

“Pashanko Dimitrov was there for trying to blow up a statue of Stalin.” Gigi referred to Bulgaria’s greatest composter. “Others were merely the victims of mistaken identity.”

“They paid a heavy price,” I thought.

In Dobrich, the TV Tower scars the landscape; it resembles a pinecone impaled halfway down a skewer. The town is named after the 14th century ruler Dobrotitsa and is another settlement founded by the Thracians.

“Once the capital of the Roman province of Moesia Inferior, it was later devastated by the 11th Century Pecheneg invasions.” Maria read from a leaflet, “Re-founded by a Turkish merchant, Dobrich became a craft and agricultural center, famous for weaving, homespun tailoring, and leatherwork.”

The region is famed for its fertile soil and Dobrich, the granary of Bulgaria, is known for its wheat, linseed oil, cheese, dried sausages, and wine.

Abounding in natural beauty, Bulgaria is sabotaged by a crippling insecurity, hence the perceived unfriendliness towards strangers.

“They think helping strangers will make them look weak and stupid.” Maria explained.

“Why are Bulgarians so insecure?” I wondered.

“You’ve had democracy for 800 years — it’s impossible for you to understand.” Maria seemed to read my thoughts.

“Do you blame the communists for everything?”

“The communists turned neighbor against neighbor. Occupation does something to the psyche, it relegates the soul.” Maria reflected, “It’s fitting that Levski was betrayed by his fellow Bulgarians.”

We passed through the city of Simeon the Great — Shumen, the monarch of the golden age. It is built within a cluster of hills, to the north of the eastern Balkan range. In the second century, the Romans built a fortress on the ruins of the Shumen. In the Holy Ascension Basilica Priests offer incantations, bells ring and incense burns, while the faithful crossed themselves thrice and kiss the icon. In 681, Khan Asparukh incorporated the territory into the First Bulgarian Empire. The following century it was razed by the Byzantine emperor Nicephorus.

“15,000 Bulgarian soldiers had their eyes gouged out.” Toshko declared. “But Khan Krum had his revenge. He captured Nicephorus and fashioned his skull into a wine chalice.”

Eventually, The Second Bulgarian Empire fell to the Ottomans under sultan Murad I.

•

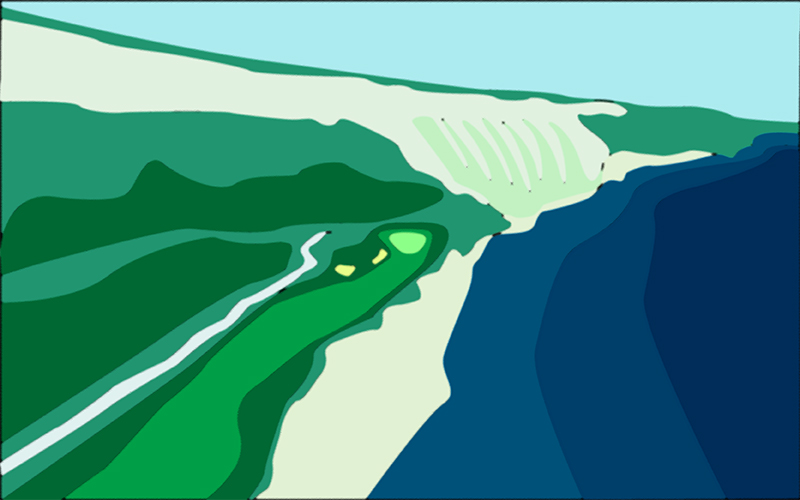

The Black Sea marked the extremity of our road trip east. The August sun had long set by the time we reached the Thracian Cliffs resort — our home for the week. Nils and I played 18 holes each morning, while Maria and her mother took up a permanent residence at the spa.

“They held the European championship here last year,” Nils boasted, surveying the immaculate course, implanted into the white cliffs.

One day, Nils and I were joined by Magnus, a chain-smoking Swede with razor sharp wit.

“An Adolf Hitler,” Magnus quipped when I played “two shots in the bunker,” followed by a cry of “Mick Jagger,” when Nils’s putt lipped out of the hole.

A son-in-law, I discovered, was a wayward drive; “not what you wanted, but it’ll have to do.”

The new money and mafia affiliates loved golf too. They were known for their brazen cheating and poor etiquette. One such bozo belched his way around the course, munching from time to time on greasy souvlaki he kept in his golf bag.

Beside the sea, Nils and Gigi seemed to transform completely in to easy-going versions of themselves.

“This is a proper holiday!” Gigi declared.

“They wouldn’t be allowed to build this anywhere else.” Nils motioned to the brand new resort and golf course transplanted into the area of outstanding natural beauty.

On occasion, we left the resort to see Varna — The Sea Capital of Bulgaria, where emigrants from Asia Minor landed in 600 BC. Later, it was integrated into Alexander the Great’s Macedonian Empire, before Tzar Kaloyan integrated the town into the Second Bulgarian Empire. A vaulted bridge spans the River Varna, but now all that remains of the old town is a few ruins and Resistance-era homes. The city center was completely rebuilt according to the quell de jour; Neo-Renaissance, Neo-Baroque, Neo-Classical, Art Nouveau, and even Art Deco. Aside from the Palace of Culture and Sports, Varna’s tourist leaflet boasts of the largest Roman Baths in the Balkans. That phrase, “the largest in the Balkan’s,” kept cropping up, from sausages to shopping malls. Everything was a competition to Bulgarians — the story of Sly Petar and Nastradin Hodja came to mind.

On another occasion, we visited the Botanical Gardens, in nearby St. Konstantin and Elena. Neither Nils nor Gigi were avid horticulturalists, so after posing for photos in front of the impressive explosions of color we headed next door to the winery. After dinner that evening, Maria and I walked hand-in-hand along the shoreline. As the sunset she became increasingly candid.

“Bulgaria is beautiful, but there is no future here. If you’re smart enough, you leave. Everyone wants to be an SBA (Successful Bulgarian Abroad), not an NSAB (Non-Successful Ass-stuck-in Bulgaria). Maria explained,

“But it’s your home?”

“It’s just the place I grew up. I don’t even have a Bulgarian passport,” Maria replied. “I grew up with all the ex-pat kids. Now, most of them have left too. There’s a film that explains it well Children of the Silent Revolution.”

Further down the beach a Chinese lantern was rising.

“Your Father’s always telling me how great Bulgaria is — like one massive playground.”

“If you were trapped somewhere, what would you tell yourself?” Maria sighed. “My Dad’s got a strange relationship with Bulgaria.”

The lantern slowly disappeared over the water into the obsidian sky.

“He arrived at a good time, but then he lost everything too. Everything except my Mother. She’s the only thing keeping him here.”

It was late August and eventually our time at the Thracian Cliffs drew to an end. Bidding the Black Sea goodbye, we jumped in the car to begin the long journey back to Sofia.

•

Thousands of storks darkened the Pontic skies as if emerging from a painting by Sliven’s famous son, Sirak Skitnik. The City of one hundred Voyvodi, captains of the Haidut liberation heroes, marks the beginning of Bulgaria’s revolutionary road.

“This is the real Bulgaria,” Toshko announced, surveying the Karandila hills and tracing the mineral springs — now mere trickles — that flowed to cleanse this pure and sacred land.

“That’s where the Ottomans hung our revolutionaries,” Gigi announced, pointing to a thousand-year-old Elm that stands in the town square. The Ottomans plunged the nation into a 500-year existential winter but Bulgaria was saved by a handful of courageous individuals. Meanwhile, language, culture, and folklore, embers of statehood, glowed in the mountain monasteries. These seeds of hope, sown down through the ages, bore fruit in the Bulgarian National Revival. Gradually, economic upsurge led to a renaissance of nationalism and inspired by neighboring uprisings, a revolutionary spirit simmered.

The road west of Sliven passes through dreamy peach orchards, valleys, and vineyards — but in the distance, the black smoke of industry looms. Plants process textiles and trucks passed enroute to Varna port.

Sliven was another Neolithic settlement, settled by the Thracian tribes of Asti, Kabileti, and Seleti, then conquered by Philip II of Macedon. Hadzhi Dimitar, the revolutionary commander, is commemorated upon a column in his hometown.

We continued on through Pazardzhik — Small Tatar Market — on the Maritsa River. Located upon an important crossroads in the region, Pazardzhik is famed for its iron, leather, and, quite surprisingly, rice. The Church of the Mother of God is famous for its ornate interior carvings, but after a while, all these churches blur into one. Pazardzhik was nearly liberated when the Russians, under Count Nikolay Kamensky, took the city in 1810. But the people of Pazardzhik were to endure three more generations of emancipation.

“The town was nearly destroyed by the Ottomans during their retreat,” Toshko mentioned. “It only survived when the charges failed to detonate.”

Further on, we passed a sign for Plovdiv, Bulgarian’s second city, and historic capital. In ten visits to Bulgaria, I never did see Plovdiv. We didn’t even pass through.

•

We stopped in Kalofer, home to the revolutionary hero and poet, Hristo Botev.

“No one has captured the spirit of the Bulgarian liberation struggle like Botev.” Toshko reflected, before reciting a portion of prose:

Do not leave a rebel heart

To grow cold in foreign land!

Do not let my voice depart Softly,

As in desert sand!

Toshko sighed.

“The April Uprising infuriated the Ottomans.” Toshko added. “They went berserk; they tried to scourge us into submission.”

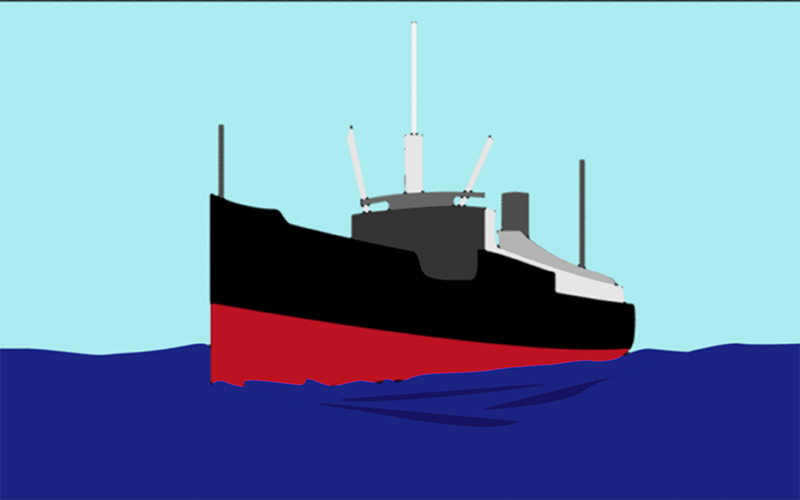

“Still, despite insurmountable odds, Botev and his fellow revolutionaries left their exile in Romania and crossed the Danube before landing at Kozloduy, where they knelt and kissed the sacred soil.” Toshko recounted the story that every Bulgarian knew by heart.

“However, news of the uprising arrived too late for support to be mustered and a catastrophe followed.”

“Carried by the liberation dream, the small detachment fought heroically to the death, and on the western Range Hristo Botev took a bullet to the heart.”

Further on, we stopped at the spot he was slain, where an inscription reads: “Your prophecy has come true.” His legend traveled far and wide.

“Botev was a prophet, not a just poet — make no mistake.” Toshko smiled.

After Kalofer, we continued on to Karlovo, the ancestral home of Botev’s revolutionary companion, Vassil Levski. The greatest of all Bulgaria’s sons, The Apostle of Freedom formed a secret network of resistance fighters to undermine the Ottoman occupation. An agile, wiry figure — with greyish-blue eyes, Levski had followed his uncle into the Sopot monastery, taking the name Ignatius. Sopot would later bear another of Bulgaria’s famous sons, Ivan Vazov, whose novel Under the Yoke forms the spine of Bulgarian literature.

Over dinner that evening, Toshko revisited this fascinating portion of history.

“Vazov practically carries Bulgarian culture on his shoulders,” Toshko began. “Like Botev, he was a romantic, infatuated with his homeland. He describes the revolutionary struggle in all its tragic glory. In every town, a street bears his name.”

“Four years later, Levski left the monastery for Serbia, where revolutionaries assembled. During the Battle of Belgrade, Levski acquired the nickname “Lionlike.” Exiled with Botev in an abandoned windmill near Bucharest, he traveled by steamship to Istanbul to embark upon a liberation journey to organize the revolutionaries. Five years before liberation, The Apostle of Freedom was betrayed, interrogated, and executed. But Levski, who had prophesied his own death, was immortalized in prose by his friend Hristo Botev.

O you, my Mother, my Native Land,

Why is your cry so sad and heart-rending!

And you, O Raven, accursed bird,

On whose grave croak you of ill impending?

I know, ah I know, you weep, my Mother,

Because you’re a slave in bondage lying,

You weep because your sacred voice

Is a helpless voice in a desert crying.Weep on, weep on! Near Sofia town

A ghastly gallows I have seen standing,

And your own son, Bulgaria,

There with dreadful force is hanging.

The winter sings its evil song,

Squalls chase the thistles in the plain,

And cold and frost and hopeless tears

Wring and twist your heart with pain.

“That force of spirit came to define a nation. Beyond liberation, Levski envisioned a pure and sacred republic of ethnic and religious equality. What remains of Levski’s dream, betrayed by the land he loved. Are his accomplishments in spite of, or because, he left the monastery?” Toshko trailed off to silence.

“Could Levski be any further from Alyosha Karazamov?” I wondered.

“Sometimes you have to leave the monastery to find God.”

A meaningful death crowns the human struggle and Levski is remembered more for his stout-hearted spirit than his revolutionary achievement. The world loves a freedom fighter, a revolutionary rising against the tyrant.

“But if everyone is fighting for freedom, who is being freed?” Toshko gazed into the darkness, “Moreover, if everyone is trying to save the world, who is left to save?”

“The revolutionary dream is at the outset pure but, the farther one realizes it, the material fleshing out of the dream changes the person. Had Levski survived and wear the ring of power, would he have become like the Sultan before him or Todorov after him, a tyrant?”

“Isn’t that the point of The Porcupine?” I reflected.

“What do you mean?” Maria asked.

The inevitability of tyranny — at the outset, Solinsky the prosecutor is pure and dogmatic, but as he descends into the detail of life under communism, and considers the legitimate authority Petkanov the dictator wielded, he grows to sympathize with the dictator. Socialism and liberalism are merely father and son. Solinsky, in performing his duty under the new system, is merely acting with the same intention as Petkanov did under the old. Solinsky grows to understand that his liberalism is the inevitable progeny of authoritarian ideology.”

“Perhaps it was a blessing that Levski never lived to see the liberation he longed for?” I wondered.

With human frailty on our mind we re-joined the highway.

•

Back on the road, a flash storm blackened the skies. On a single stretch, we saw two crashes and one road-side wreckage — the scorched asphalt and pools of standing water created a lethal slick. The storm had long passed when we pulled up in the town of the lime-trees, Stara Zagora. Beneath her streets lies the Roman city of Augusta Trayana, where The Emperor Traianus once trod. The Tzar Simeon Veliki boulevard adjoins two well-proportioned parks; to the west, Fifth of October and Ayazmoko to the east, housing The Defenders memorial. Facing the park, a Renaissance-era house, birthplace of the dissident poet Geo Milev, is now a museum. We relaxed in the Ayazmoko park, later visiting the hourglass-shaped History museum.

“It dates from at least 7th BC,” the brochure boasts, “The crypt houses relics dating back 12,000 years.”

Later that day, we detoured south to Alexandrovo village, with its Thracian tombs and frescos, and Trigrad village, where we caught sight of the Rhodope Mountains. That evening Toshko was in fine spirits and over Rakia and coke we heard about the Devil’s Throat cave, where Orpheus descended into the underworld to save Eurydice.

Eventually, the curtain fell on that immortal summer. Maria departed to university in Sweden and I returned to my studies in England. In time we graduated, settled down, and embarked on travels of our own, but always found our way back to Bulgaria. Even after settling in London, we returned every few months to celebrate the holidays, weddings, and long weekends. In time I came to love the adventure and the chaos, the exuberance of this flawed, but equally misunderstood race. Bulgaria welcomed me into her sacred heart but deep down I knew my time here could only end in tragedy.

•

And so it was that, four years later, I touched down in Bulgaria for the final time — alone, on a business trip. The flight over was not long enough to dream back to that invincible summer. Neither were the intervening years. Destined to be nothing more than a single protracted kiss goodbye. Now the relationship lay in tatters as we passed each other in the fast lane on the down-slope of a marriage. At arrivals, I was greeted by a different face. She was not radiant but frigid and gaunt. There was no abandonment to nature, no object of affection, no personal connection. I thought of the Thracian rider journeying through the underworld, but never looking back.

“How did it go?” Maria called from London. We only ever spoke on the phone.

“Bulgaria is not the same without you.”

“I’m looking forward for us to return together once all this is over.”

But we never did. Late that night Nils drove me to the airport.

“How did it go?” He asked.

“I don’t even know why I bothered coming . . . typical Bulgaria.”

“You thought you could beat Bulgaria,” Nils laughed.

“With you on the inside . . . I was certain! How can you work with these people!”

“One day you’ll understand.”

On that final note, I slung my rucksack over my shoulder and headed into the terminal. “No, do not look back,” Eurydice whispered, as flames engulfed the memories of love. In time I would realize how pure and sacred these people are, how misunderstood, how perfect they are. How I thought I could play her game, but in the end, I was exposed. Chewed up and spat out. Now the life ebbed from my Bulgarian dream. Surveying the runway and the Sofia lights in the distance, I cracked open a Kamniza for the last time and toasted the night sky. Bulgaria you stole my heart, goodbye.

This is a work of creative nonfiction. Names have been changed and some creative choices have been made for the purpose of the narrative.